We are furious farmworkers. This text is the fifth inquiry from our forthcoming book: Farmworker fury – Inquiries about organic agriculture. Previous chapters can be found here, here , here and here.

In 2020, we read Class Power on Zero Hours by the AngryWorkers. It left us buzzing. After some time of not knowing what to do with our inspiration, we decided to write this book about our work experiences. Leftists often either romanticize (organic) agriculture, or they want it to be fully automated and industrialised. Beyond capitalism, we will have to learn to work the land in a truly sustainable way. Therefore, we think it’s important to have a workers-based analysis of (organic) agriculture. We are writing this book to contribute to such an analysis and we are hoping to receive feedback, comments and critiques from fellow workers and comrades.

Click here for a PDF of this chapter…

About the Collective-Cooperative

For three months, we worked on a collectively run vegetable farm somewhere in the German speaking world. The core team is a collective [1] producing certified organic vegetables on 50 hectares of land since decades.

The founders (only men) of the collective came from the ‘alternative’ movement of the 1970s and 1980s. The collective arose from a desire to organise working together differently than in the usual top-down business models, and to do something practical instead of just protesting. Many similar collective cooperatives that began during this period failed sooner or later. Many gave up in times of economic hardship. In others, the legal owners took over and continued to run the business as a conventional company (the law does not accept alternative/collective/anarchist forms of ownership but requires a liable owner). Here we encountered a rare case where this had not happened. So we were incredibly curious to find out what was going on.

The cooperative operates around 20 market stalls per week at regional weekly markets. It also supplies two organic wholesalers and around half a dozen independent organic shops. Around 22 employees make up the collective (we call them collectivists).

The majority of them work full-time or more than full-time (40-48 hours per week). About one-third of the collectivists work less than full-time on various hourly schedules. During summer saturday is a regular work day on the farm. At the weekly markets, saturday is a regular work day throughout the whole year.

The collective additionally employs around 70 people throughout the year who prefer normal wage work without the extra responsibility of collective membership. These are mainly part-time jobs, for example sales staff at market stalls, a cleaner or truck drivers who deliver goods. They live nearby and work 15 to 30 hours per week. There is also a group of about fifteen seasonal workers who come every year during the high season. Many are from Poland, some from Romania, and there were two Ukrainian women during our stay. The total workforce is equivalent to approximately 40 full-time positions (including the market stalls).

The hourly wage was €13.80 gross for collectivists (at that time three euros above the minimum wage). All other employees were grouped into three wage levels: €12.30, €12.80 and €13.30. The lowest level, at that time €1.50 above the legal minimum wage, was the wage for seasonal workers in their first year. From the second season onwards, it was €12.80. Nowhere else in our own working lives or in the stories of other people, we did encounter a company of this size with such small wage differences.

The cooperative does not own any land: The fields and the farm are leased. The farm used to be an ornamental plant nursery with decades old run down greenhouses. The collective refitted the premises a lot. Buildings were converted or adapted, and new buildings were erected. The lease is long-term (with a 10-year notice period).

Legal Framework

Legally, the company is a registered cooperative. At the heart of the cooperative is the workers’ collective. The collectivists are the members of the cooperative. The registered cooperative is the legal body operating the company. The cooperative owns the means of production and holds the lease agreements. Legally, a registered cooperative must have a board of supervisors, and chairmen, etc. These requirements are formally met. Some collectivists put their names down on paper for those roles. Matter of fact, the collectivists organise themselves as a direct democratic group that makes decisions together. And is sharing the tasks of managing the farm. This also means that the collective is the boss of the employees (permanent employees, seasonal workers, temporary helping hands, sales people, drivers, etc.).

All members of the collective must be actively working in the company. Decisions on hiring/firing workers and admitting workers to join the collective are made by consensus. Decisions on technical issues, such as the purchase of new equipment, are made by majority vote (with 51% constituting a majority). The aim is to make decisions that are supported by the majority and to avoid crucial votes. Somewhere there is a statement of principles in which this is also written down. However, this was only written down ages after the company was founded. Collectivists legally join the cooperative by signing to a cooperative share worth €100. At the same time, the collectivists are employed by the cooperative. They are therefore their own bosses.

Organising the work

The daily work is divided among fixed departments. These are: harvest, outdoor cultivation, greenhouse cultivation, young plants nursery, workshop, markets and office. Each department has a spokesperson/coordinator. How coordination is done in detail is left to the respective departments. For example, the management of the harvest rotates between three workers. The outdoor team, on the other hand, is always coordinated by the same person. Some departments consist of only one person.

The regular work day is 8 hours. The collective holds two daily meetings to organise the work and discuss minor and major issues. Work begins at 7:45 a.m. with the first meeting, which usually takes five to ten minutes. Here, the team coordinators explain what needs to be done that day. There is a certain amount of flexibility in terms of who works in which team, depending on peak workloads, the weather forecast and how much work needs to be done overall.

For the collective the lunch break is from 12:15 to 13:15. The seasonal workers have their lunch break from 11:30 to 12:00. This allows them to take their break undisturbed by their bosses (the collective members). This way it was easier to keep distance from each other during the covid pandemic. For the collective, the first half hour of the break is the actual break and time for lunch. All collective members pay a fixed monthly contribution for lunch. Lunch consists of bread, spreads, cheese, tea, coffee and of course vegetables. Occasionally, one of the collectivists cooks a hot meal for everyone. For example, on birthdays. The second half of the lunch break (30 minutes) is the second work meeting of the day.

This meeting is held unpaid in break time. First, the afternoon work is organised, then there is time to discuss everything related to the management of the business. While we were there, the topics ranged from planning a summer party, to job applications, investments in equipment or vehicles, and reviewing the business numbers. Sometimes confidential collective issues were discussed. We had to leave the room for this, as we were only seasonal workers and not members of the collective. We were (pleasantly) surprised that there was absolutely no gossip or backbiting. We never found out what confidential matters were actually discussed internally.

All workers, whether employees or collectivists, earn money by doing wage work. In addition, the collectivists (unpaidly) share management and planning tasks. In a conventional company this is the responsibility of the owner/capitalist. If necessary, additional meetings are held after work, which may be counted as working time or unpaid. Whether a meeting is paid or unpaid is decided jointly in advance, in case of doubt by majority vote. There are no owners skimming off the profits of the business. The collective decides jointly how profits are used: For new investments, as back up, for wage increases or something else entirely.

Several times, neighbours from the village or neighbor farmers from the area came by to ask for help or a favour. Once, a neighbouring conventional farmer came by to borrow a specific tractor for a specific task. As the machine in question is very sensitive, the collective decided to lend a collectivist along with the tractor and machinery for the rate of covering costs. As a thank you, we received a lot of cake. Really a lot of cake. A collectivist commented: ‘Yes, you have to understand that it’s not money that keeps up good spirit in business, but sugar or cake’ :-).

We always received our wages and payslips on time. Of course overtime was paid. If we had any questions about the paperwork, these were answered quickly.

Work processes and workers’ intelligence

The work processes in this company are very well organised. We always had sharp knives and good equipment. For people who do not work in horticulture themselves, it’s usually astonishing to hear that many farms don’t even manage to provide their workers with sharp harvesting knives. The cooperative had all kinds of harvesting knives in all sizes. One collectivist is responsible for sharpening the knives with electric sharpeners. If this worker is absent, she is always replaced by the same colleague. The collective figured out that the knives lasts longer when they are always sharpened and maintained by the same person. Different people would sharpen the knives at slightly different angles, causing them to wear out more quickly. When knives are needed for harvesting, the harvesting team takes the matching sharpened knives to the field in a yellow plastic box the size of a shoebox. After use, the knives are collected in a red plastic box and returned to the sharpening station. After being sharpened again, they are ready for the next use.

For us, this is a perfect example of workers’ intelligence. This process is logical and straightforward, yet we don’t know of a single other vegetable farm that does it this way. The collective decided early on that it would be cheaper and more efficient in the long run to purchase several additional tractors for specific machines rather than owning only a few tractors and having to constantly attach and detach machinery. As a result, more different tasks can be carried out parallelly within the regular 8-hour working day.

The weed management was impressive – highly proactive and always early on. ‘The best time to control weeds is before they are visible, or at the latest at the cotyledon stage.’ said a senior collectivist. If this works out, there is much less manual hoeing and weeding than on other farms (see chapter 4 ). You probably have to hoe or weed the areas just as often or even more often than if you wait until the weeds are bigger, but the work is much quicker. For example, a Chenopodium album is quicker to hoe out when it is still in the cotyledon stage than if you wait a few weeks until it towers above the vegetables.

The bed lengths are standardised so that work processes and equipment are all adapted to this specific length. This means that a bed is always 100 metres long and each set of vegetables that is sown/planted at once always covers a gross area of approx. 1,000 square metres = 6 beds, each 100 metres long, with a path next to it (of course there are a few exceptions). Standardised bed lengths make certain work processes easier, such as finding insect protection nets, irrigation materials and cover fleeces in the right size. This also makes it easier to calculate the required amount of seeds or nursery plants, estimate the expected yield and make the corresponding calculations for weekly wholesale offers.

This is similar to the small-scale market gardening approach. [2] Here it is done on a larger scale. The collective realised, even if some beds are 110 m or 130 m long, they do not make any additional profit by growing vegetables on these extra metres, as it complicates all the above-mentioned work processes (“Damn, where is that extra-long cover again, in the pile with all the normal-length covers… and that extension for irrigation that we only need once a year… Oooh, forgotten, no idea…”). So some field edges are simply open ground or grassland.

Our average workday

We worked in this veggie farm from the beginning of April to the end of June. Working hours were usually from 7:45 a.m. to 4:45 p.m., monday to friday, with about three saturdays a month (on these days, we usually finished earlier). We rarely worked overtime (apart from saturdays). During the season! In agriculture! Unbelievable! Really! Our colleagues told us that things had been different the previous year: For about four weeks, they had been short-staffed by four seasonal workers.

In summer, depending on the weather forecast, the harvest team often started between 6 and 7 a.m. to get the harvest from the field to the washing machine and processing it in time before the heat sets in. The seasonal workers in the harvest team finished work earlier on these days, while the collective members still worked until 4:45 p.m., thus accumulating overtime.

We had many different tasks, which made our working days diverse and less boring. Each task involved a different type of physical exhaustion, so it never became too strenuous. Sometimes we had to do very monotonous tasks, such as washing and sorting carrots or beetroot on a conveyor belt, but the team coordinators made sure that such tasks were rotated. Sometimes you had to do this kind of work all day, but then you could also ask to swap with someone else half way.

We mainly worked in the harvesting team and in the greenhouse. At the beginning of April, lamb’s lettuce, radishes and parsley were still being harvested in the greenhouses. At that time, only leeks were harvested outdoors. Later in the season, we also harvested radishes, spinach, bundles of carrots, rhubarb, potatoes, various lettuces, fennel, cauliflower, broccoli, kohlrabi, pak choi, Swiss chard and other vegetables in the outdoor fields. In total, the farm grows 40 different vegetables. Harvesting also includes washing and preparing the produce ready for delivery to customers: weighing and packing it into crates, stacking it on pallets and labeling it.

We also spent a lot of time in the greenhouses. From mid-April onwards, we planted tomatoes and cucumbers in the greenhouses. And this is how it works:

First, the soil in the greenhouses must be prepared. A small tractor with a rotary tiller tills the soil. Next, the future beds and footpaths between the beds are marked out. Drip hoses for irrigation are laid out and checked for functionality. The beds are covered with black plastic mulch sheets. This covers the soil and prevents weeds from growing. Holes are cut into the mulch sheets at regular intervals. The nursery plants are planted into the soil by hand through the holes.

The tomato and cucumber seedlings were sown in the nursery and grown in heated nursery greenhouses. Once ready the plants are packed into boxes, stacked on pallets and transported to the greenhouses by forklift: First, the plants are packed into boxes by hand, six tomato plants per box. The boxes are stacked on pallets. A forklift transports the plants from the nursery to the greenhouse. And here the whole process is reversed: the boxes are unstacked from the pallets by hand, the plants are taken out of the boxes and planted in the planting holes at exactly the right distance (60 cm) apart. Next, the plants are watered with a hose so that the potting soil mixes well with the greenhouse soil and the roots can grow well.

If tomato plants are left undisturbed by humans, they grow into large random bushes with many side branches and countless small fruits. The plants do not grow upwards because they are too heavy to support their own weight. Harvesting would be very annoying and unprofitable for commercial cultivation. The plants need some kind of structure. A lot of work throughout the season therefore goes into putting up support strings and winding the plants around these strings. In summer, the plants grow very quickly and need to be wound once or twice per week. Winding is a job that must be done carefully, otherwise the fruit can break off, or worse, the entire plant. Winding tomato and cucumber plants also involves removing the side shoots. This is called pruning. Otherwise, the plant puts all its energy into the side shoots instead of stronger branches and larger fruits. Depending on how tall the plants are, workers must either work in a bent down position, kneeling, or stretching. If the plant is as tall as the worker, they are fortunate and the posture is comfortable. If the plants are very tall, workers can climb onto work carts to do the job in a good position.

Of course, it can get very hot in the greenhouse in summer, and even easy tasks can be sweaty. One way the farm tries to deal with this is to do greenhouse work early in the morning with a larger group of colleagues. Later in the day, the greenhouse team can help out in other departments. Another option is to base the weekly work schedule on the weather forecast. This means greenhouse work on cooler, rainy, cloudy days. Usually, there are not enough cloudy days in summer to get the greenhouse work done… So we sweat.

Housing

The farm rents several flats in the village to accommodate its seasonal workers. We lived in a furnished room in one of these houses. This cost us around €150 per person per month (including all costs like electricity, internet etc.). At the beginning (in April), we were alone in the large house, and at the end of our stay (late June), the house was fully occupied. Eight of us stayed in six rooms (two rooms were used by couples). On the ground floor, the five of us shared a large kitchen, a bathroom with a toilet, a separate toilet and a huge garden with a beautiful terrace and a cherry tree. The house was well looked after. It felt a bit like a holiday home: the rooms were furnished, the beds had good mattresses and the kitchen was fully equipped. TV and internet worked reliably, which was important for our Polish colleagues, watching Polish news and staying in touch with family and friends in Poland. We were well looked after in every way, even with garden chairs, a barbecue and beautiful flowers.

The lawn was mowed regularly. The company provided bicycles for all seasonal workers. We commuted to the veggie farm in ten minutes by bike. Our Polish colleagues preferred to travel together in a car, which they took home from work every day and also used for weekly shopping. We were happy with the bicycles and also used them to go on a few trips in the area.

Nevertheless, we lived in close quarters. At one point, a gastrointestinal infection spread among the staff. Two colleagues in our building also fell ill, but fortunately not everyone was infected. Luckily, we had no covid infections in the house. There was an covid outbreak at work, but it was quickly traced and contained. The company provided a huge supply of rapid tests for the staff. When some colleagues found out they had covid infections, everyone at the company got tested. Ten colleagues tested positive, but only five were confirmed by a positive PCR test result the following day. Those infected stayed at home for as long as necessary, and no one pressured them to return to work before they had fully recovered.

Our housemates, who were in the majority from Poland, did not speak much German or English, and we did not speak Polish, so we did not talk much to each other. They usually worked a six-day week and used their free time to keep in touch with relatives. They brought large quantities of food supplies from Poland, storing loads in the freezer and went shopping at discount supermarkets. Occasionally, we would have a lemonade with some colleagues after work, provided by the farm.

In total, we stayed for 13 weeks on farm. We took a few days off in between to visit friends. This was easily possible when arranged in advance. On average we worked 45.8 hours per week on the collective wage rate of €13.80 per hour gross (€9.37 net). At the time, this was €3.50 higher than minimum wage. This corresponds to €8,216 gross in three months per person, which is €1,862 net per month. If we had not gone on any trips or made any other non-essential purchases, it would have been possible to save around €6,700 between the two of us. Of course, this is a different story for people with children, relatives in need of care or other duties.

Health and safety

In stark contrast to many other companies we have worked for, occupational safety and accident prevention are taken very serious at the cooperative. At the beginning of our stay, we received an hour-long briefing on occupational safety and potential hazards on site. Among other things, we were told where to find first aid kits and telephones and which colleagues are trained as first aiders. In addition, there was a detailed (really very detailed) forklift training session. The collective ensures that there is always enough suitable equipment for all employees, such as gloves, ear muffs, rainwear, aprons, rubber boots, sun hats and sun screen. Machines, forklifts and tractors may only be used after instruction by more experienced colleagues. One weak point was that only one collectivist was in charge of these health and safety briefings. When he was busy, it took longer to receive certain instructions. At the time, we did not find out how the instructions for non-German-speaking colleagues was done.

On several occasions, we noticed the collectivists adhering to health and safety standards, even if this meant that some tasks took longer to complete. Some collectivists explained to us that an accident costs the company much more time, effort and money than simply taking a little longer to complete the task and work safely. However, some of our colleagues did not consider it so important to work carefully and in accordance with health and safety regulations. If someone does not want to use sunscreen, hats or ear protection, there is not much you can do.

Atmosphere

The atmosphere in this workplace is mostly friendly and welcoming. We did not have to listen to sexist, racist or chauvinist bullshit, as is the case in many other companies. [3] What we particularly liked was the clarity in aims: The cooperative is a business and has to make profit. Many so-called ‘alternative’ projects (which we now prefer to refer to as hobby or self-realisation projects) often lack a clear objective. In addition, the atmosphere is down-to-earth, without subcultural jargon. The focus is to work, not on talking about how amazingly ‘different’ and ‘sustainable’ it is. Many customers at the market stalls do not even know that this company is run as collective-cooperative. What really matters is the production of high-quality vegetables. In our experience, this down-to-earth mentality is very rare in ‘left-wing projects’ (see chapters 1, Eco Village and chapter 4 on CSA).

Within the collective exists unity, that it is important that employees are able to safely operate the vehicles and machinery needed for the company’s daily operations (forklifts, cars and around seventeen different tractors). It was encouraging to see it went withtout saying that many (young) women were driving tractors and forklifts.

During the work meetings, we noticed the older collectivists (50 years and older), who have been working in the collective for twenty or more years, taking up more speaking time, than the younger ones (aged mid-twenties to mid-forties). One younger collectivist, who is very attached to the place, told us: He had learned in the collective that there are always a few people who feel inclined to say something at the end of a discussion. He simply accepts that they need this space and that in reality things will go on anyways.

On hierarchies

Some collectivists have managing or coordinating tasks. It seemed to us that those roles did not become part of their personal identity. The tasks of a farm manager or farm owner are distributed among the collective, with some taking on more responsibility than others. For us, this made a big difference in our daily work.

Of course, there are hierarchies in the sense that some collectivists are more committed and motivated, work longer hours or have more skills or experience. However, these social differences are not transmitted in wages or other formalised differences. For example, there is no boss who owns the business and therefore decides who does what. People with coordination tasks still do practical work and more tedious chores, such as hoeing or washing carrots. There is a set hourly wage, which at the time was €13.80 gross per hour. Seasonal workers and part-time workers have different tax brackets, so their gross wages vary slightly. However, the aim is to achieve a somewhat equal net wage for all. The only exception to this rule is one office worker: It was impossible to find a trained office worker willing to work on the collective wage rate. So her wage is about 1€ higher.

Of course, there is a power imbalance between the collectivists and the other employees of the cooperative. After all, the collectivists decide about hiring and firing. For us, it made a big difference that even the coordinators are expected to perform monotonous tasks. In other companies, it is common practice to assign these tasks to the lowest-paid employees.

Excursion: Ecological pragmatic compromises on the free market

Our time at this veggie farm has shown us the importance and, at the same time, the shortcomings of organic agriculture. There are many practices which comply with official organic certification standards but still may be improved from a strict ideological-idealistic environmentalist point of view. It has shown us that certified organic agriculture is necessary but far from sufficient.

We need to understand the global economic relations of food production in order to understand the impact of our work and recognise how those work processes set us into collaboration with workers around the world. An (organic) vegetable farm is not an island, but part of global supply chains. In academic left-wing theories, this is also referred to as global socio-ecological metabolism. [4] Few examples:

Use of peat soil for plant nursery

The cooperative’s nursery plants are grown in potting soil consisting of 70% peat and 30% compost. Peat extraction requires the drainage of wetlands. This process releases large amounts of CO². It also results in the loss of species-rich wet habitats.

Use of seeds from all around the world

One of the tomato varieties grown on this farm comes from certified organic tomato seeds propagated in Thailand. Procuring these seeds locally is very difficult, if not impossible.

Use of hybrid seeds [5]

The farm (as almost all (veggie) farms) uses hybrid seeds, as these varieties are better suited to large-scale commercial production. The reason for this is that they generally produce higher yields and ripen more evenly, which means that a certain batch of vegetables can be harvested with less effort.

We are not opposed to the use of hybrid seeds on principal. It is simply important to recognise that this leads to dependence on specialist companies in the current economic system. Seed production and seed propagation in industrialised agriculture has been outsourced to specialist companies already since decades. Doing things differently would be quite complicated, and farmers/horticulturalist would have to re-learn lost skills in propagation cultivation.

Purchase of nursery plants from a specialist vegetable plant nursery

These nurseries specialise in the production of young plants and can produce them more cost-effectively than smaller, on-site propagation units. As a result, many vegetable growers no longer cultivate their own young plants, leading to a loss of expertise and competence. In Germany, there are only four to ten certified organic nurseries, which produce more or less all organically traded nursery plants for commercial production. This sometimes leads to long transport routes. This can also become problematic if plant diseases or pest populations spread unnoticed in the nursery and are passed on to farms across regions with the nursery plants.

Use of plastic

Regional vegetable production with the longest possible season means that techniques for early cultivation must also be used in the open field: For this reason, many plastic sheets and cover fleeces are used to protect the plants from late frosts in spring or to accelerate growth slightly. There are also many different types of plastic netting used to protect against pests such as aphids, flea beetles and cabbage white butterflies. These nets are difficult to recycle when they are discarded after a few years. They end up in the residual waste. A grower friend of mine remarked that since travelling through India and Central Asia, she has seen very different mountains of rubbish and (non-)concepts of waste prevention and disposal, and that the few fleeces from an organic nursery are not the most pressing waste problem in the world. Another veggie grower friend remarks that he likes to cut out this comment, as it follows the classic excuse of ‘the others have to do it first’.

Use of animal nitrogen fertilisers

The cooperative mainly uses hair meal pellets and sometimes horn meal. These fertilisers are obtained from the ground horns of slaughtered cattle or pig bristles. Certified organic slaughterhouses do not produce significant quantities of these materials. Organic meat has only a tiny market share. Therefore, organic guidelines allow the use of horn meal and hair meal pellets from conventional slaughterhouse waste. We do not know exactly where the fertilisers used by the cooperative come from and under what conditions they are produced, but we do not have very positive images in our minds… In any case, the meat industry does not care how the organic sector fertilises its land, and this waste product exists in the world nevertheless. The question is rather how the industrial meat industry could be drastically reduced in size. This may free up arable land, previously used to grow fodder. Fertiliser crops could be experimented with here. However, this is a technical discussion that we cannot do justice to in this short text.

Use of fossil fuels for heating

This farm used very old greenhouses, heated with oil, resulting in very high heating costs. During our stay, the collective began to grow tomatoes in a more energy-efficient way: instead of planting the young tomato plants in a heated greenhouse at the beginning of April (the heating switches on when the temperature falls below a certain level), this year the tomatoes were sown two weeks later and not planted into the soil until mid-April. This meant lower heating costs, but also a later start of the tomato harvest.

Use of a whole range of fossil fuel powered machines

For environmental reasons, the heavy use of machines in professional agricultural operations, including organic farms, is highly problematic. Matter of fact diesel and tractors cost only a fraction of what 100% manual labour would cost per hour. Many people from (middle-class) ‘eco’ bubbles or green social milieus that we know seem unaware of what it means practically, for example, to stop using a tractor-mounted hoe but to weed or harvest carrots exclusively by hand, or to dig with a spade instead of ploughing. This is certainly possible, but we have no idea how the corresponding labour costs would be reflected in food prices.

What will happen in agriculture in case of severe shortcomings in diesel supplies? Or if energy prices rose sharply? Of course, we must radically reduce the consumption of (fossil) energy. In doing so, it is important to compare the consumption of fossil fuels in agriculture with that of other sectors and to examine how useful the respective products are. After all, vegetable and food production makes more sense than, say, the production of weapons, fast fashion, highly processed unhealthy foods, Red Bull energy drinks in aluminium cans, SUVs, private jets, cruise ships, or server capacities to stream cute cuddle cat videos online anytime, anywhere…

Use of specially bred beneficial insects

Chemical pesticides are not permitted in organic farming. An alternative strategy is to use beneficial insects that (can) eat/attack pest populations. These beneficial insects are a market of their own. They are bred in special laboratories and sent via mail. Bumblebees are also widely used for pollination in greenhouses. Bottlenecks in delivery can very quickly lead to serious problems in many organic (and conventional) vegetable farms. Beneficial insect companies keep their laboratory breeding methods secret. We are curious to get in touch with colleagues who work there.

Marketing vegetables via many scattered market stalls

Compared to the goods turnover and logistics systems of supermarkets, the distribution of vegetables via many different market stalls is very inefficient (per unit); considering how far the vegetables have to be transported in small batches in different directions. At the market, a stall is only set up for a few hours and then dismantled again. At each weekly market location, only a tiny fraction of the city’s inhabitants buy their vegetables at the weekly market. But of course, the veggie farm cannot force the immediate neighbourhood to consume its entire production. After all, we live in a capitalist society, and free choice in the (super)market or discounter is a progressive achievement. Anything else may cause socialism.

The vegetable farm is part of a global socio-ecological metabolism. Like any agricultural business, it is integrated into global supply chains. Many of the smaller projects we visited strongly emphasised the importance of marketing their products ‘locally’. We wonder how much of a difference this actually makes when most of the inputs come from all over the world. For example, small farms often rely on a high proportion of compost that is produced elsewhere and delivered by trucks. And they often rely on young plants that are produced in specialised young plant nurseries.

All of these issues listed above, are ecological and pragmatic compromises, which are common practice in organic vegetable growing and organic agriculture. This is not a specific criticism of this vegetable cooperative, but simply the reality of the situation.

When we tell colleagues or comrades from smaller businesses or collectives/cooperatives about this veggie farm, they are often disappointed by the ‘conventional’ conditions and pragmatic horticultural compromises, or even just by the way people interact with each other in everyday working life: ‘But in a collective, everyone is equal… They rarely hold longer plenary meetings… and they work sooo much.’

When we meet colleagues and people with professional experience in agriculture or horticulture, they are often impressed by the high level of equality among collectivists and colleagues in this farm. For them it is impressive, that professionally growing vegetables is possible with largely humane working hours, complying the 40-hour week and part-time models as common practice. There is no bullying or exclusion. For some farmers, the fact that such a business can exist without a heavily indebted owner sounds like a miracle.

Conclusions: Thoughts on collectives, cooperatives and class struggle

We have many fond memories of working in this collective cooperative, but also some unanswered questions. What role can or should collective/cooperative enterprises play in revolutionary moments?And along the way: What does the continuation of grassroots union/operaist [6] approaches look like in worker-led companies with relatively good working conditions?

Is it more reasonable to fight for improvements in lousy companies with very shitty working conditions and to organise accordingly? Are collective enterprises capable (or willing) to show solidarity with workers in other companies? Or in other words: How can class struggles continue if the workers have already taken over the company and its means of production and are managing it?

Collective/cooperative work can significantly improve the quality of life and work on a daily level. However, it is wishful thinking to believe that capitalism and exploitation can be abolished solely by establishing more workers’ cooperatives: On a small scale, it is quite possible to imagine that workers as a collective, with a high degree of motivation, autonomy, initiative and cooperation on an equal footing (equal wages), without a boss, can successfully plan, manage and execute complex work processes. Not having to put up with ridiculous foremen and their pretentionous fuss makes capitalism at least somewhat more bearable.

At the same time, this mode of operation does not change the fact that the veggie farm is in structural competition with other producers on the so-called free market (product quality, availability, prices, etc.). Ultimately, these formalities cannot determine whether the workforce, as individuals or as a collective, is willing to build practical, solidarity-based relationships with workers in other companies and industries and to behave accordingly in terms of class politics. If one is comfortable enough in one’s own circumstances, inertia may set in. It is also questionable how a collective wage relates to union tariff agreements with hierarchical wage levels. In the worst case, the cooperative is a wage squeezer toiling below union agreements(?).

On a global (and national) scale, wealth continues to be redistributed upwards, and the profits and concentration of power/capital of large corporations continue to grow… It’s always the same story. How boring.

Another challenge we encountered is that the collectivists have to be both bosses and workers. The pressure to compete in the market is borne by the entire collective rather than by a single owner. This can be a relief, but it leads to a kind of class struggle within oneself. During our time there, for example, the sales turnover of one of the weekly market stalls shrinked. Instead of three salespeople, there was only enough work for two salespeople left on this weekly market day. For a long-time employee of the cooperative, this meant fewer working hours at this market stall, even though it was clear that it might be difficult for this person. There were considerations to offer the employee shifts at another market stall. We do not know how the story ended.

Taking responsibility for the business also means that the ‘guilty conscience’ when calling in sick is a little louder than elsewhere. If a collectivist falls ill, it means the other members have to fill the gap, meanwhile statutory sick pay continues to be paid of course. Some collectivists find it difficult to switch off from work in their free time. They feel a huge sense of responsibility.

Anyways, we perceived work motivation in general to be significantly higher than in comparable companies, as was the scale of unasked independent thinking along in work processes. During peak periods or quiet periods, colleagues are much more willing to work longer or shorter hours on a flexible basis.

Sometimes we noticed that individual seasonal workers were less motivated when working beyond the direct supervision of the collectivists. For example, they were less careful when weeding, or when winding up the tomato plants. Strings got wound too tight or too loose. In the worst case this results in broken tomato plants. Once, we observed some seasonal workers driving at 30 km/h on a 70 km/h road so. Prolonging the time sitting in the car between two tasks.

To which extent does the usual ‘revenge of the oppressed’ of workers against their bosses by working slowly or messy make sense when the bosses are workers like themselves? Sometimes we wondered which group of workers actually gets the ‘better’ deal: The collectivists, bearing the entrepreneurial risk and spending unpaid working hours on meetings. Or the seasonal workers, who are paid (almost) the same wage and return home at the end of the season? In their home countries their money has a greater purchasing power. Unlike the collectivists, the long-term employees and seasonal workers ‘only’ have to work, without having to spend time and mental capacity to unpaid collective meetings.

While proofreading this text, a comrade added:

“Motivation cannot be explained primarily by better deals or privileges. Rather motivation is explained by the fact that workers feel connected and in control of their work. Those overseeing the bigger picture, therefore know that certain tasks need to be done will do them. Seasonal workers were hardly involved in the overall planning, if at all. Therefore they are more likely to just work to rule. It was no different in the GDR: Formally, the peoples-owned enterprises (VEB) certainly belonged to the people. But “the people” do not care if they have no say in the matter and just dawdle around during work hours…”

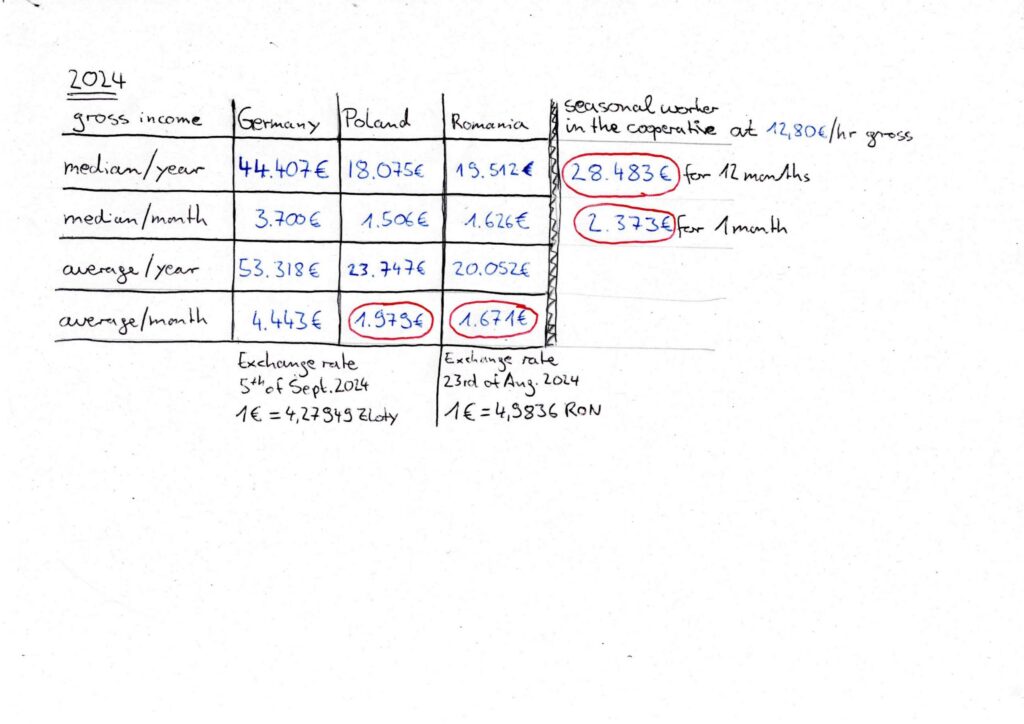

This index compiled by the Federal German Statistical Office compares the cost of living for households in different countries. If Germany is assigned 100 index points, the cost of living in Poland is calculated at 66 points and in Romania at 58 points. [7]

If you worked full-time on this vegetable farm for a year at an hourly wage of €12.80 gross, you earn a gross income of €28,483 (€2,373 per month). Compared to the median income of €44,407 or the average income of €53,318 per year in Germany, this is a low income. Nevertheless, this wage is significantly higher than the wage level in Poland. There, the median income is equivalent to €18,075 per year (€1,506 per month) and the average income is €23,747 (€1,979 per month). In Romania, the median annual income is equivalent to €19,512 (€1,626 per month) and the average income is €20,052 (€1,671 per month). In any case, incomes in agriculture in these countries are far from any average values. National differences in weekly working hours, holiday entitlements, sickness and old-age benefits are not taken into account in this brief comparison.

We write this because it might be interesting to question the widespread victim narrative that is often used when talking about seasonal workers. It is noteworthy that many seasonal workers have been returning to this vegetable cooperative every year for decades, some for thirty years. Experience knows that workers do not stay that long if the working conditions are too bad. New seasonal workers are not recruited through a temporary employment agency, but on the recommendation of other seasonal workers. All in all, it seems that many people like the workplace. We have hardly heard of any other workplace with rather good comparable conditions for seasonal workers; most of the time, it is as described by comrades from Notesfrombelow: https://notesfrombelow.org/article/workers-inquiry-seasonal-agricultural-labour-uk-sh or something like that https://notesfrombelow.org/article/struggle-agricultural-workers-italy. For a broader overview: https://notesfrombelow.org/issue/seeds-struggle-food-time-crisis.

The collectivists share management tasks and responsibilities, but also the more delicate, creative work and long-term planning and strategy tasks. Their wages are rather high when they start as unskilled workers or straight after training, but older, more experienced collectivists could earn 50-90% more money as team leaders or operations managers on other veggie farms. However, they have decided against this and prefer to work collectively, with equal pay and all the social challenges that come along with collective cooperative work modes.

Is it ideology that motivates people to stay, or is it being rooted in the region? In our opinion, it is a combination of both: The people who stayed had social and family ties or other commitments in the village. Some decided they would rather work in a collective than start their own business, becoming a boss and spending the rest of their lives paying off a mortgage to the bank.

Some of the older collectivists are couples with both partners working in the cooperative. And somehow some of them have managed to finance their own homes and raise children. Although they work for low wages, they have been able to achieve a certain degree of material security.

Role in case of a workers’ uprising

What will happen in this farm if a significant proportion of the country’s workers dared to revolt against the capitalist economic system? If workers stopped paying rent and stopped doing useless jobs? If we placed the economy under democratic self-management and refused to continue destroying the environment?

If the cooperative stopped paying rent, it would run into problems with the landlords who lease land and business premises to the them. How would the collectivists respond to this? The main landlord is a family, who is not only earning money from leasing land, but also running a farm themselves. Other relatives of the landlords run a business in the village. They are very well integrated into the small-town community and are involved in local cultural initiatives and the Green Party. This would therefore lead to serious conflicts in the village.

In practical terms, the question will be in which cities and industries such a revolt may begin and how quickly it will spillover to rural areas. It is questionable under which circumstances and conditions farmers and horticulturalists will supply insurgent communities with food instead of continuing to produce for money on the market. It is also questionable who will take over and manage the cold storage and warehouses of the wholesalers, to whom the cooperative is selling produce. Hopefully it is the workforce taking over the wholesalers.

According to the film The Loud Spring, in the event of such an uprising, we may focus on truly useful work and stop doing bullshit jobs. Which jobs are really bullshit jobs reaches beyond the scope of this text. Anyways there are countless jobs, done because they generate profit in the current capitalist economy, or because someone is paid to do them. However, upon reasonable consideration, they are utterly useless: Advertising, influencers, designers for app-controlled coffee machines, ocean cruise ships, the tobacco industry and many more. If we stop these useless jobs and put our work force into reasonable and useful work, the average working day might be reduced to three hours, claims The Loud Spring.

The remaining time is set free for reproductive labor of all sorts and democratic self-organisation in neighbourhood assemblies. Or for other things we desire doing.

It is difficult to calculate, but we are concerned in this regard. At least in the mid term, agricultural work cannot be done in three hours a day. If a large number of people with no agricultural experience suddenly joined this cooperative, it would initially cause a lot of work to coordinate and train everyone.

Vegetable calculations

Currently, this veggie farm annually sells approximately 885 tonnes of vegetables each year. This requires in total 60,000 working hours per year in cultivation (excluding the retail department). This results in an average productivity of 14.75 kg of vegetables in retail quality per working hour. [8] Transport and marketing are not included here. Converted to full-time job equivalents, this requires 34.65 horticulturalists working a 40-hour week.

The annual yield of 885 tons divided by the 34.65 full-time positions results in a productivity of 25.54 tons per full-time worker (equivalent) in this veggie cooperative. At the current level of technological development. This figure is, of course, only a rough guide, as it simply lumps together all crops from coriander to potatoes, carrots and lettuce. Furthermore, even in economically successful years, the total amount of produce sold is smaller than the quantity actually produced: Sometimes things go wrong and vegetables that are nutritious and edible cannot be sold because nobody wants to buy them or because they do not meet primarily aesthetic marketing requirements – too small, too large, too this, too that, blah blah blah. In other words, the gap between quality does not meet retail demands and literally starving is very huge. In true emergencies, people do not make a fuss about eating aesthetically inadequate or even ugly vegetables.

This allows us to estimate how many people the yield can nourish per year: The current per capita consumption of vegetables in Germany is around 100 kg annually. Roughly estimated, this means that the 50-hectare veggie farm covers the current vegetable demands of 8,850 people in terms of quantity alone. In this farm’s cultivation system, this means an area of 56.6 m² is required to meet the annual consumption of 100 kg of vegetables per person. This rough estimate does not take into account many important factors, such as seasonal fluctuations and the variety of vegetable types.

8,850 people sounds like a lot. However, this number is far below even supplying the 40,000 inhabitants of the nearest town. To do so, four to five veggie farms of this kind are needed only here.

Now, one might argue that there is not enough arable land available. Obviously, all available arable land is already being cultivated. In a post-capitalist, socio-ecologically reasonable world, one possible consequence it to eat much less meat and grow correspondingly less fodder – thus freeing up arable land for vegetable cultivation and fertiliser crops. The current global trade routes for food may have to be reconsidered in each individual case. Even a per capita consumption of 200 kg of vegetables per year can be covered. The neighbouring land of this veggie farm is farmed conventionally. Animal fodder, energy crops for biogas plants, potatoes and sugar beet for the food industry are grown here, also for export.

The current food consumption of the population in Germany, with its current eating habits, requires 16.6 million hectares of farm land worldwide. [9]

At the same time, in total approximately 16.5 million hectares of land in Germany is used for agriculture. That is about half of the country’s total surface. In purely mathematical terms, this may be enough space available locally. However, we are not talking here about banana and coffee imports or meat imports and exports. 13.8% of agricultural producers in Germany cultivate 10.8% of this area according to certified organic standards. That is 1,784,002 hectares (in 2021). [10]

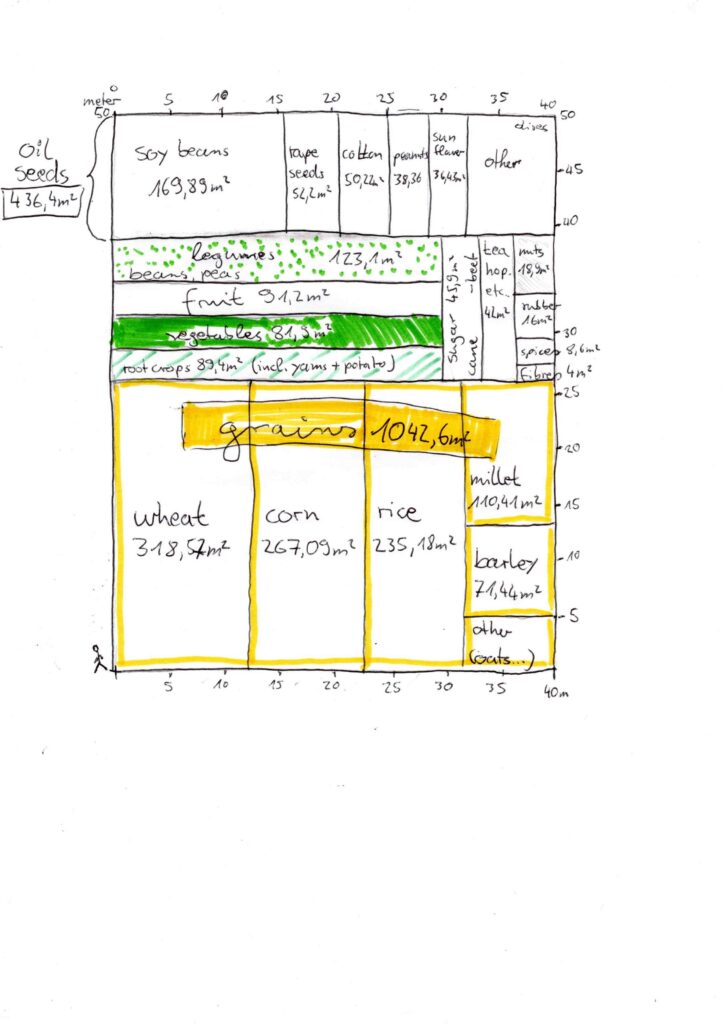

According to the Zukunftsstifung Landwirtschaft (=Future Foundation for Agriculture), which runs educational projects such as Berlin’s Weltacker, there is 1.6 billion hectares of usable farmland available worldwide. [11] Divided by the total world population, this means that 2,000 m² are available per person. [12] Of those 2000 m², 81.9 m² are for vegetables, 89.4 m² for roots (potatoes, yams, etc.) and 123.1 m² for legumes, adding up to 294.4 m². With a predominantly plant-based diet and reasonable land use, the globally available arable land should still be able to feed a world population of 9 billion people in 2050. [13]

As mentioned above, the veggie cooperative in this chapter needs an area of 56.6 m² for 100 kg of marketable vegetables, or 113.2 m² for 200 kg of vegetables per year. Depending on the categorisation of the individual vegetable crops, this cultivation system can be compliant with the available land in the 2000 m² Weltacker model calculations.

Footnotes

[1] Registered co-operative or just co-op (Genossenschaft e.G. in German), refers to the official legal structure of the farm. The expression collective refers to the social mode of organising the farm.

[2] A market garden is a small-scale farm which often markets its produce locally and directly. A small patch of land is used very intensively and efficiently. Usually, market gardens do not use heavy machinery, which saves space as you don’t need driveways for big tractors. Comprehensively explained in this book: https://themarketgardener.com/books/the-market-gardener/ . Jean-Martin Fortier. The market gardener book. Or in these youtube talks: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0hBUOdv2vn8&list=PLiM0T_Y7peh-2sjP2oC2ZgI7IPIbhMURr (both accessed 10th of January 2025).

[3] We only understood German and English. We did not understand what some seasonal colleagues said in Polish or other languages.

[4] Back in the day already Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels spent a lot of time writing about this and in particular the metabolic rift. For a rough introduction Der Öko Marx by John Bellamy Foster, published in Le Monde Diplomatique 7th of June 2018: https://monde-diplomatique.de/artikel/!5508514 (accessed on 1st of December 2025). More recently Kohai Saito’s writings caused renewed attention to the issue in recent years.

[5] We discuss the advantages and disadvantages of hybrid seeds in our first chapter: https://www.angryworkers.org/2023/01/29/farmworker-fury-inquiries-about-organic-agriculture/ Hybrid seeds have to be bought anew every year from agro-chemical corporations, which creates long-term dependencies. Using non-hybrids seeds is a bit like using free- or open source software, anyone is free to experiment and breed with those seeds or to make their own seeds. This is very interesting when thinking about truly sustainable agro-ecological systems that can function without the industrial-capitalist agricultural industry. However, hybrid seeds are very common in conventional and organic horticulture because yields are higher and crops grow more uniform.

[6] Operaism means a non-dogmatic workers-focussed neo-marxist current, which strongly inspires us for this text and helps us analyse. For an overview https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operaismus (accessed on 8th of Februar 2025). Or even better: https://www.angryworkers.org/2021/10/03/the-renaissance-of-operaismo-wildcat/

[7] All data in this paragraph: https://timeular.com/de/durchschnittsgehalt/polen/ ,

https://timeular.com/de/durchschnittsgehalt/rumanien/ and https://www.capital.de/karriere/medianeinkommen–so-viel-verdienen-die-deutschen-im-mittel-31108506.html accessed on 6th of January 2025.

[8] Calculations in this paragraph:

885,000kg of vegetables divided by 60,000 work hours = 14.75kg per working hour

One horticultural worker working a 40 hour working week, sums up to 1731.6 work hours per year: 52.5 calendar weeks minus 5 weeks annual holiday minus 2 weeks sick leave minus 9 public holidays.

All data taken from the veggie cooperative in 2020

[9] Michael Berger, Elisa Kollenda & Maja-Catrin Riecher. (2024). DER BLICK ÜBER DEN TELLERAND in BODENATLAS Daten und Fakten über eine lebenswichtige Ressource. Hrsg: Heinrich Böll Stiftung, BUND Friends of the Earth Germany, TMG ThinkTank for Sustainability Töpfer Müller Gaßner. https://www.boell.de/de/bodenatlas (accessed 11th of January 2025).

[10] All data: BRANCHEN REPORT 2022 Ökologische Lebensmittelwirtschaft. Hrsg. BÖLW. Bund Ökologische Lebensmittelwirtschaft. The umbrella organisation of several German organic growers asociations.

[11] https://www.2000m2.eu/de/ (accessed 11th of January 2025).

[12] Christine Chemnitz. Endlichkeit der Landwirtschaft. (2018). in: FLEISCHATLAS Daten und Fakten über Tiere als Nahrungsmittel. Hrsg.: Heinrich Böll Stiftung, BUND Friends of the Earth Germany, Le Monde diplomatique. https://www.boell.de/de/fleischatlas (accessed 11th of January 2025).

[13] https://www.2000m2.eu/wp-content/uploads/Weltacker_Broschure_2024_web.pdf (accessed 11th of January 2025).