You can read a short summary about the struggles described in the book here and watch a documentary here. We published the introduction to the book here. Translating this book seems worthwhile for two reasons. Firstly, at least in the English-speaking world, there is little historical material about autonomous communist working class organisation in Italy in the 1960s and 1970s that does not focus on either factories or the question of reproduction. Secondly, despite the fact that the times and conditions have changed, we can still learn a lot from these experiences. The book inspires us as we plan to organise a revolutionary hospital workers’ newspaper and collective in 2024. Watch this space!

What is the teaching hospital?

The Policlinico Umberto I was founded at the beginning of the 20th century as a nursing hospital for the poor, managed by the Pius Institute together with the St. Spirito hospital. In the following decades, the hospital developed more according to the requirements of the medical faculty to which it is attached [1] than according to the needs of its potential patients.

In 1971, when the independent workers’ struggle began, the Policlinico comprised seven departments – the so-called ‘pavilions’ – with a total 763 beds, administered by the regional health board, and 42 clinics with 3,285 beds, which were dependent on the university (and therefore on the Ministry for Education).

Considering that in the public sector in Rome there are only 13,739 hospital beds, it becomes clear that the Policlinico represents one of the major centres in the health system of the city, which in its entirety is largely insufficient for a population of about 3 million inhabitants (without taking into account that a continuous stream of patients from the south of Italy is burdening the hospitals in Rome, where there is even a greater lack of hospitals).

But it is also necessary to know that while the pavilions are organised like a ‘normal’ hospital and at least aim at providing medical care, the clinics, on the other hand, given that they constitute the ‘teaching hospital’, provide care only in a way that is subordinated to their institutional purpose, which is the professional education of medical personnel (in order to show a student how you treat a patient, the patient is also treated). Therefore the clinics are subjected to a particular regime that makes them barely suited to the purpose of providing care.

Nevertheless, the faculty of medicine is not satisfied with the situation, and intends to expand further, proposing repeatedly to turn the entire Policlinico into an Institute for higher research [2]. would be a severe misfortune for the popular masses of the capital and for the workers of the hospital. We will see why.

The characteristics of the ‘teaching hospital’ can be summarised in the following way.

The first characteristic is the selection of patients. As far as possible, the clinics don’t treat the popular masses in the surrounding neighbourhoods based on their needs. Patients, including those coming from other regions, are chosen based on their illness (taking into account also the background of their social class). This selection happens according to a precise order of priorities: first of all those patients are chosen who have an illness which is of interest for current research purposes, both in terms of pure and applied research, which means that patients become guinea pigs for pharmaceutical experiments. This is followed by those patients who have an ‘interesting’ illness in terms of being showcases for the students or specialists. The third category of patients are those who have common illnesses, who are therefore of interest for the specialists to ‘practice on’.

While the first two categories of patients (for research and teaching purposes) are chosen from amongst the proletarian patients who come to the general hospital admission desk (the so-called ‘warehouse’), or the admission desk of the clinics, the third category of patients (which is the only one that is merely ‘treated’) has a different provenance. These are the ‘patients of the director’ who have already been filtered through private surgeries for diagnosis, but who, for example, cannot afford the actual treatment in the private clinic of the director, or who have a recommendation from one of the medical barons to undergo – more or less free of charge – expensive examinations which the private clinics are not able to perform. This means that even those patients who are in the hospital just to be ‘cured’ – and there are some, which demonstrates that the Policlinico would be able to provide actual treatment if that was wanted – are not patients who just happen to be there. Patients who have just turned up randomly at the admission desks, and who are not ‘chosen’ by any of the clinics, are discharged after a few days. In the meantime, they have perhaps caught another hospital-related infection from the neighbouring beds, given that all patients are piled up on each other without distinction. They are transferred to other hospitals in the city which, given that they are not ‘teaching’ hospitals, cannot refuse them.

The second characteristic is the lack of nursing staff. In contrast to the large numbers of doctors, due to the ‘teaching needs’ of the numerous students [3], there is a scarcity of paramedical staff such as porters, nurses and technicians. There are around 2,700 of them, officially employed for learning and research purposes, but also employed as care workers, while from a nursing perspective a workforce of 4,500 would be necessary,because these 2,700 don’t all engage in proper nursing work, given the fact that in the clinics they are preferentially used as messengers or typists and therefore only engage in care work on paper. And the doctors certainly would not debase themselves to perform the work of porters, which results in a very reduced scope to perform care work – even when the potential (and availability) of staff working overtime is taken into account. Therefore the teaching hospital ends up with a good number of empty beds. Between 1964 and 1974 on average only 75% [4] of all beds were used, in contrast to the ‘pavilions’ where the patients are piled up even in the corridors and bathrooms.

The third characteristic is the irregular nature of the work relation of the nursing workers. The irregularity starts with the clientelist hiring process, which is – to say the truth – not much different from those in other hospitals. There is not a single worker in the Policlinico who wouldn’t admit they got hired because ‘they already knew someone’ – and because, in many cases, they have been recommended to the university baron, the head of the personnel department or the head sister by the priest of the parish of their village, by the secretary of the local section of the DC (Democratic Party) or another government party or, finally, by the trade union. Such an entry to the workforce then defines the behaviour that is expected by this ‘clientele’: becoming members of the recommending political party or trade union or performing, as part of their work, all kinds of informal personal services or other activities for their ‘guardians’, in particular services which have nothing to do with nursing. It’s enough to think about election campaigns, when the nuns and boot-lickers of all kinds become active to ‘defend the free world’ by banking the entire votes of the hospital workers and their families, of the patients and their relatives for the bosses of the DC, or other government parties (the Policlinico has always been a solid fiefdom of the DC).

If we keep these premises in mind, it is easy to understand how the behaviour of those who have succeeded in getting hired by the Policlinico is constricted, and in which ways their labour is from then on actually regulated. As the workers of the clinics are employed by the Ministry of Public Education for the requirements of teaching and research, and given the fact that their work contract is that of a public servant, it is not presumed that they perform other types of labour, as these would not be officially recognised. However, these workers perform actual nursing labour, with specific job tasks, shift patterns and regulations that are absolutely different from those of any other ‘ministerial worker’. For example, the official working day of employees of the Ministry is six hours long, from 8am to 2pm, while the workers in the clinics work shifts (of eight hours, plus two hours overtime, on all days of the week, also on bank holidays). The Ministry employs them as ‘janitors’, while they work as porters, nurses and also perform other nursing tasks. The Ministry rules out night-shifts and hazardous work [5], while these workers do both.

This situation is the source of great discrimination towards these workers, in addition to the difficulties it creates when it comes to caring for patients. You would not ask a janitor to know how to administer an injection, or take someone’s blood pressure, etc.. Now, while it happens on one hand that a worker who has been hired without particular skills (as a janitor you only need to have passed the fifth elementary school class) can learn how to do their work, to take the lead from the patients and to gradually take on tasks with greater responsibility; on the other hand, the irregularity of their work relation will never be cured. Management pretends to solve some of these issues by paying compensations [6], but many others are sources for a particular subordination of the workers regarding their two bosses – the Ministry and the director of the clinics.

Let’s start with the question of the organisation of work within the clinic. As there is not a legal status with a job description that would assign particular tasks to workers with the respective competence and diploma (and how could you, if everyone is a ‘janitor’?); and because it is only prescribed that in the ‘research institutes’ the workers do ‘whatever is necessary for the requirements of research’ – meaning, the insidious requirements of the barons – the workers find themselves at the mercy of the will of the latter, who assign heavier or lighter work tasks as they please, dish out recognitions and punishments, grant overtime and career advancements as they see fit, and put one worker against the other in order to consolidate their power in the clinic. The barons use a whole array of loyal lieutenants for this management of the ‘administration’ of their clientele: nuns, head nurses, secretaries, foremen and forewomen who have been chosen by them, and only answer to them in order to make sure that everything runs according to their will.

There is therefore an issue of the relationship between tasks and qualifications. The majority of workers who have been hired as janitors (a qualification corresponding to the qualification of a porter, who is only supposed to undertake cleaning and transport tasks) actually perform the work of technicians, nurses, head nurses etc. Yet their formal status, in terms of contract and pay, is that of a janitor.

Often, in order to get around the ‘rigidity of the law’, workers who find themselves in such a situation pursue professional training courses in technical institutes, of their own accord.: In order to get a salary commensurate with the tasks performed in the hospital, these workers try to enforce a formal qualification (a ‘patentino’or license) which they obtained outside the hospital. There is a lot to say about the difference between what they learn ‘in theory’ in these institutes, and the hard practical reality of a profession which they already know very well!. Naturally, this adjustment of the wage also depends on the whim of the barons. Once the patentino has been obtained, in order to transfer to the higher job category (for example, that of a nurse), the worker needs a ‘’ from the director of the clinic, declaring that the work has been performed in a ‘commendable’ fashion. If the baron does not want to issue this note, the worker will not be promoted, even if they have the diploma. [7]

Finally, there’s the question of the stablility of the work relationship. If a messenger employed by the Ministry accrues a certain amount of years seniority they can, if they pass a trial period, be promoted to a superior role. Can such a thing happen to a janitor who works as a nurse? As there is no official trace of the fact that they work as a nurse, that they have a diploma etc., the janitor in the clinic – in contrast to the messenger in the Ministry – can accrue endless stages of seniority without there being any planned career progression, for example from janitor to ‘health supervisor’. To circumvent these career ladder problems, management only issues annually-renewable contracts for janitors. In this way, the issue of accruing seniority is avoided. It means, in substance, that because they are not in one of the the nursing job categories, they belong to no job category at all. And here we’re still dealing with ‘permanent’ work relations.. here are many cases of truly precarious work contracts: workers who are hired for 88 days (because this means that they cannot prove three months of continuous service, which would give them a legal entitlement to a permanent contract), who are then sent home and re-hired after a few months.

There are even workers who are only hired for the day, the ‘giornalieri’ (day labourers), the true ‘hands of nursing’: these present themselves every morning to see if they can substitute for absent workers. They don’t have a fixed work contract and are paid for the day!! [8]

These normative aspects, so to speak, of the clientelist organisation of the clinics have a profound impact too on the behaviour of those who experience the subordinate side of this reality on a daily level: the workers and patients.

Given the precarious situation in which they find themselves, and the climate of ruthless competition with their colleagues, the main activity expected from a worker is to humour the barons in any way, hoping for some special compensation. In this way, the worker is alienated from their work, they don’t exercise any kind of control over it, and step by step they are dragged into becoming accomplices of antipopular medicine, into not giving a fuck about the patients, and into seeing them only as awkward objects on which to perform the tasks that the barons demand. They think that they don’t have any other interest apart from becoming a public servant and receiving a wage to get by.

The patients, on the other hand, who have submitted to the image of the baron as the great luminary of science on which their cure depends, find themselves in daily contact with the workers and their attitude of ‘I don’t give a damn’. This pushes the patients into blaming the workers for their bad medical treatment, and to trying to win the benevolence of the barons by all means (with gifts and favours). If all this shows that in this type of hospital the nursing aspect is subordinated to the research purposes, what type of health care is then actually given? And what is its relationship to the care given in other hospital units?

Too answer this question, it’s important to keep other factors in mind. In a social organisation that aims at the realisation of profits and accumulation, even the performance of medical services is oriented towards that goal.

There is a private sector which says openly that its aim is to create a profit from the health needs of the middle-class, and which organises itself to be able to offer ever more adequate services, also using the infrastructure that the state specifically provides. For example, by sending their own patients to public hospitals when it is necessary to use very expensive technology for examinations which only the state can afford to purchase; or by applying new treatments or medication that have already been tried on proletarian patients in public hospitals.

Then there is the public sector, which pretends to mediate social antagonisms by reducing class differences when it comes to sickness and health care (“the medicine which cures both rich and poor”) – whereas in reality, it offers a service for proletarians which does not aim at the reconstitution of their health, but rather at the reproduction of their labour power, so that capital is able to make use of it again.

The bourgeois patient can afford to pay for better services offered by private clinics [9], and their relationship with the doctor – even if they are treated in a university clinic – is a contractual relation between equals. [10] “The bosses are treated in the private clinics and they are supposed to recover completely in order to be able to perform again, with their full faculties, in their role as exploiters. With the bosses you cannot mess things up”, says the Collective. By contrast proletarian patients, who are nursed because they are covered by health insurance, receive treatment according to their subordinate position in society. “In the Policlinico, proletarians are only patched up and sent back to their place of work and exploitation, and if they die during the process, which often happens, it is just a common mishap”, continues the Collective. [11]

Often, the proletarian patient has personally experienced the dual reality of the private and public medical system, and can draw comparisons. A patient who was treated at the neurosurgical clinic directed by Guidetti said during an assembly: “As long as I had money I stayed at Villa Giulia, where Guidetti was very kind and thoughtful. Now that the money has run out and that I am here through the common health insurance, Guidetti ignores me completely, as if I wasn’t me anymore”.

We can conclude,contrary to the common sense that claims care provision at the Policlinico is better because the doctors there are more ‘knowledgeable’ thhat proletarian patients misfortunate enough to arrive here receive the worst care possible within this ‘stopgap medicine’ practiced at the public hospitals for the mere purpose of reproducing labour power, and also being treated as guinea pigs And within this classist organisation of medicine lies the reason for this ‘misfortune’ afflicting the socially most vulnerable people, who, apart from not being able to afford better care in the private clinics, are also not prepared to protect themselves against the abuses of medical trials, which they would not be subjected to in ‘normal’ hospitals.

Workers, students and the struggle for health

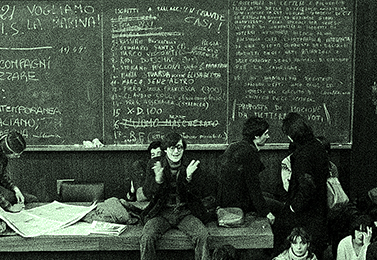

Reflecting the aspect of oppression experienced by workers and patients, in the moment of the great awakening that followed the student and workers’ struggles of 1968-69, a new consciousness emerged among some hospital workers, with a new watchword: defeat class medicine and the power of the barons, unite workers and patients in the struggle against the teaching hospital. The realisation of this programme will be a long and tortuous process before being taken up by the oppressed masses, for whom it represents the only possibility of liberation.

Before the start of the struggle of nursing staff in the university clinics against the teaching hospital, the Policlinico already witnessed the agitation of the Collective of medical students which proposed two goals: “no to class medicine” and “doctors should be educated in those places where sickness originates”. These very general slogans managed to create a progressive sector among medical students, who are, by social background and aspiration, the most integrated in the classist dimension of education that they receive. But they had not yet facilitated an alliance between progressive students and all those – hospital workers and proletarian patients – who could, and need to be, united against the target of the hour: the university barons.

The political limitations of both the students’ and workers’ actions can be seen as a root cause of this failed alliance. On one side there was a typical ‘workerist’ idealism amongst the students, which, in their search for the proletariat, didn’t see it in the porters or the patients on the hospital wards, and with whom there would have been lots of things to talk about. Instead they were chasing it amongst the factory workers of the metal manufacturing sector in Tiburtina, to whom they later on proposed discourses from the outside about science not being neutral, and about exploitation as a reason for physical harm, which, to be fair, remained abstract; because these discourses were not the product of an elaboration taking the experiences of these workers as a starting point.

On the other side, the weakness of the workers’ actions were due to the corporatist politics of trade union organisations which only took care of the economic issues – and even that only just about – and which were organised in a way that discriminated against the workers in the clinics, and the little influence they had within the hospital.

Firstly, workers who perform the same tasks and who work side by side in the same part of the hospital were members of two different trade unions, depending on the institutions that they belonged to. The workers of the pavilions were part of the Federation of Hospital Workers (Federazione lavoratori ospedalieri), whereas the workers of the clinics were members of SUNPU (Joint national union of university staff CGIL-CISL-UIL / Sindacato unitario nazionale personale universitario), an organisation of state employees. [12]

The former, who were part of a collective contract, entered into dispute once the contract had to be renegotiated and perhaps went on strike a few times for the ‘health reform’. The latter mobilised themselves whenever the union agitated state employees, and perhaps in order to support ‘bureaucratic reform’.

Sometimes SUNPU had to take care of these particular ‘state employees’ because they lacked the usual cover of job security (and therefore security of income). In these cases, SUNPU adapted itself to a role recognised by those in power when it comes to precarious labour, in particular when it is bordering unemployment: forming a clientele and pushing for an ad hoc intervention of the ministry. Occasionally the latter then concedes a small legal measure [13] in order to control the dissatisfaction of the workers, and to correct a situation which has become too irregular or, alternatively, the ministry puts vacancies out for irregular workers to compete for. In this way, while the union reinforces its role as an intermediary [14], the minister and his party gain votes in subsequent elections.

So workers were never mobilised around the general issues at the core of their precarious employment, or concrete problems of their work. Their cases were dealt with on an individual basis, or at the most as cases of a few people spread across various clinics, between whom the unions acted as middle-men. Ministers who were out of reach were asked to provide solutions, and workers had no control whatsoever over the proceedings of negotiations concerning them.

When, later on, the union wanted to take the complex situation of the workers in the clinics into consideration, they always did it in a way that emphasised the ‘difference’ between them and other nursing workers; meaning, their condition as state employees. For example they pushed for struggles that aimed at getting recognition for the special status of research work, or at equalisation with other state employees. [15] In this way, they end up aggravating the discrimination of the workers in the clinics, and reducing the possibility of creating a force of all hospital and university workers around the problems of nursing.

In spring 1971 some clinic workers wanting to organise a struggle around their working conditions had extracted themselves from the clientelist politics of SUNPU. They started to meet up with a group of medical students. This group had formed during an ‘external’ intervention in the industrial area of Tiburtina with the environmental commission of the local council.

The outcome of this experience in Tiburtina, which took place during the time the collective contract in metal manufacturing came up for renewal and which focussed on the problem of toxic working conditions in the factories, led to a division between the students. On one side there were those who saw the outcome as positive. They intended to continue working within the Collective of Medicine as it were (essentially an instrument for the political socialisation of students) [16] and could imagine the creation of stable links with the popular masses only through the support of the trade union left. [17] On the other side there were those who saw the political limits of the experience. They criticised the fact that the relation between the students and the exploited masses was based on the subordination to the trade union line, also because the students had no precise role in this action. According to their view, to engage in an external intervention of such a kind, however related to the discourse about the qualification of a doctor, is an escape – a symptom of the inability to struggle on one’s own terrain (which is, instead, the contradiction with the university barons). And this is even more mistaken in a moment where the workers of the clinics started to develop their struggle against the barons.

In this way the second group of students (some of whom had found work as technicians or analysts at the clinics in the meantime, and would later on have a determining role in the leadership of the struggle) identified the possibility of unifying students and clinic workers in a common struggle against the barons, with the objective of a ‘proletarian management of the hospital’ appealing to all the social forces interested in the struggle for health – hospital workers, the popular masses who live in the surrounding neighbourhoods and who should have been ‘served’ by the hospital, the worker-patients and the progressive students. The Collective of Workers and Students at the Policlinico emerged on this basis.

This different way to impose the struggle for health inside of the hospital (contrary to what was said later on by those who continue within the Collective of Medicine) does not mean abandoning the students as subjects of this struggle, but calling back onto the terrain where their action can be more specific, and therefore more autonomous. The clinic barons are also their professors at university.. In the course of the subsequent struggle against the ‘teaching hospital’, which is in itself an objective of progressive students (certainly not those who want to make an academic career!), there were multiple times when the Collective of Workers and Students at the Policlinico tried to involve the students in struggles dealing with concrete aspects of their subordination within the faculty and hospitals in which they ‘exercise’. For example, during one of the many times when the barons tried to turn the entire Policlinico into a teaching hospital, the Collective addressed the students with the following words, explaining to them that such an institutional change would oppress them more, and calling them to struggle together with the workers:

“They try to keep students ever more distant from the hospitals where day-to-day medicine is practiced, in order to prevent them from understanding which role medical practice has today: enriching oneself on the backs of the patient by curing diseases without understanding their true causes, which are based on exploitation. This is the most fundamental fact that emerges from the workers’ and student struggle, which the students should take into account if they really want to operate within the framework of a true class struggle. While it is true that amongst the students there are ‘daddy’s sons’ who are not interested in combating the strategy of the barons in white coats, there are also proletarian students who know what the exploitation is that they suffer day in and day out, and who oppose and mobilise themselves against the bosses and their lackeys. Until now all the objectives that students have put forward (research collectives, alternative educational programs etc.) have not been obtained, as they evidently don’t hit the bosses’ organisation in its vital parts. Today, instead, we want exactly that: to destroy the barons’ strategy and their sources of wealth at their foundation. Comrades, it is necessary to join the struggle of the workers at the university clinics […] Currently we organise ourselves to beat the anti-worker structures of the faculty which uphold the mystification of the tasks of medicine during lectures and later on during the exams”. (12th of February 1973)

However, the major novelty, when it comes to the way the Collective of Workers and Students at the Policlinico engaged with the struggle for health, concerned other aspects.

Firstly, the Collective emphasised the need to define the proletarian struggle for health in a different way, having developed a critique of the subordination in which the students found themselves regarding the trade union line. “To fight for the defence of health means to confront day in and day out the mechanisms and structure through which the bosses manage the exploitation of workers: the home, the school, the transport system, the health system should increasingly become terrain of conflict beyond the factory; it is those struggles that break the isolation of workers, which gather workers of all sectors for a common class struggle”. [18] If instead, one remains within the confines of the factory and doesn’t struggle for the defense of the physical integrity of the proletariat in all moments of social life, it becomes more likely that the struggle against toxic working conditions becomes ‘monetarised’, meaning, that the workers’ health is considered like a thing (a commodity) that has simply to be sold at a higher price and that one gets imprisoned within a normal ‘trade union dispute’. [19]

Here we come across a second issue. The popular masses, who express a need for health at the moment when they come into contact with the institutions that are supposed to satisfy their needs, invariably face a series of concrete problems: there are no hospitals or they are located far away; often you have to pay bribes to enter; [20] health insurance doesn’t cover certain services; the university clinics give a different treatment depending on economic considerations and they use proletarian patients as guinea pigs etc.

But within these oppressive structures a more favourable situation can open up for the proletarian patient once a contradiction develops between the nursing workers and the group of ‘political-scientific’ leaders (in the case of the Policlinico, the barons of the university clinics), meaning that once the workers develop a consciousness that the subordination they suffer depends on the fact that, although they produce a service that is necessary for the masses, they work for the dominant classes, who at the same time oppress the popular masses and enrich themselves through their labour.

While in other institutions which have purely repressive or controlling purposes towards the masses, such as the state bureaucracy, the police force etc., workers are separated both from power and from the masses they oppress, in the hospital, on the contrary (like in other ‘social’ services that the state has gradually incorporated) the presence of the masses themselves tends to burst open the internal class contradiction, and workers’ struggle cannot then disregard it. [21]

Based on this general assessment of the condition of proletarians regarding the issue of health, workers who joined the Collective and linked up to the external struggles refused their privileged position as ‘state employees’ or as ‘guard dogs’ of power who are placed above the masses right from the start. They struggled against all divisions between workers (and against all corporatist actions that maintained them) in order to blow up the repressive function of the hospital and to create a unity between workers and patients. [22] Therefore: “No to the teaching and research hospital; yes, instead, to a hospital that provides care and that unites the hospital and university workers” (10th of November 1972).

This position is the foundation stone for the slogans of the day: “Proletarian management of health”, “No to the exploitation of workers and patients” [23] and of the objective for the transfer of all workers in the clinics to the administrative entity of the hospital, which characterised the Collective right since its emergence.

In this longer quote from one of the Collective’s first leaflets, it becomes clear how they explain to the masses their decision to constitute themselves as an independent organisation:

“The function of the state in our country is to be a repressive apparatus in the hands of the bosses, in order to keep the workers in a relation of exploitation.

- State employees understand that within the differences amongst themselves, they work in entirely different sectors.

- Employees of the ministries, for example, live within the bureaucracy and are as such neither directly situated within the productive apparatus, which is the factory, nor within social services, which is the school and the health sector, and therefore they don’t live in direct contact with the general problems of the working class.

- In contrast to this, the non-teaching staff of the university and the university clinics work within social services such as the school and the hospital.

These workers therefore feel the very contradictions of these structures directly, the problems that stem from the bosses’ power in the school and most of all in the health sector, and the profound insufficiencies that afflict these social sectors. From all this emerges the necessity for profound and radical changes.

- Through their work they are in daily contact with workers who fall sick, because the subordination to exploitation continues not only at the assembly lines, but also in the poor ghettoised neighbourhoods, in the city where you no longer move around and up. From these relationships emerges a new consciousness which pushes the clinic workers to join up with all other workers in order to destroy this violence.

- Finally, all university workers are in contact with the students, which in recent years have expressed, through their struggle at the side of the workers, the will to combat the exploitation by bosses and barons in schools and the entire society.

The struggles the university workers have conducted so far show that they lagged behind struggles of other workers, for example the hospital workers, who were initially perceived as having a status inferior to the university workers. They enforced such levels of economic improvements that their treatment is now superior to that of their university colleagues,and they are even considered as having drawn ‘the golden ticket’.

“All this has happened not because there are ‘better’ workers and ‘worse’ workers, but because the potential of the university workers to struggle has been limited by the fact that they are intimately linked to the staff of the ministry and all the other state employees in general, including the medium and upper level of the bureaucrats. The struggles and strikes […] were therefore not able to disengage from a logic that was wholly internal to the system. Despite themselves, the university workers were then forced to reduce the qualitative scope of their demands and to lead cooperative struggles, for example, for the maintenance of privileged status, including private payments for hospital rooms or for outpatient services etc.” (18th of May 1971)

From this moment on the collective took their own action forward, clarifying their position wherever the occasion emerged, emphasising the objectives of the struggle within which the masses could be organised, explaining better the objective to abolish the teaching hospital.

It was a struggle that developed in alternating phases, which in some moments saw the collective limiting itself to contrasting the actions of the trade union with a different discourse, and in other moments saw autonomous initiatives – also on an organisational level. Initially the Collective was composed of a minority of workers from the clinics. Bit by bit the collective’s discourse imposed itself, and the SUNPU first became a minority and then disappeared. The discourse started in 1971 and had a first significant success in spring 1974, which delivered a heavy blow to the subordination of workers and the power of the barons: the transfer of the clinic workers to the general hospital staff. From this moment a new phase, and new pitfalls, opened up in which the challenge of leading the struggle against the monopolistic power of the state and capital in the health sector intertwined with the challenge to counteract the advance of revisionism, which appeared under the new disguise of the ‘democratic management of the hospital’. In the following chapters we will reconstruct the phases of this process.

Footnotes

[1] For the period from May 1971 to the beginning of December 1973, the quotations of the leaflets of the Collective of Workers and Students at the Policlinico are signed with the simple mentioning of the date. We indicate explicitly those cases where the leaflets have a different signature. The requirements of the medical faculty increased with the rising numbers of students (600 enrolments in 1964, 4,000 in 1974) and professors (from 40 to 120 during the same period).

[2] The faculty demands the application of law no. 1140 from the 26th of October 1964, whose enactment has so far been postponed, which stipulates “regulations for the separation of the Policlinico Umberto I in Rome from the administration of the Pius Institute of the Holy Spirit and the assignment of the entire complex to the University of Rome”, “for the requirements of expansion and modernisation of the clinics and the institutes of the Faculty of Medicine and Chirurgy” (article 1). The law stipulates the construction of a hospital with 1,000 beds and a boarding school for 280 students (article 2). Within two years from the time of granting the loan for the new hospital, the process of transferring the ‘pavilions’ to the university is supposed to start and to be concluded within four years. (article 6)

[3] In the Policlinico there is on average one doctor for every 4 patients, or 1 for 2 if we also consider specialised doctors. In other hospitals, in comparison, the ratio is 1 doctor for 7 patients. However, these averages don’t make sense if they are not seen within a particular context. There are some clinics where there are more doctors than patients (which is not surprising, if you want to study a very rare medical case!), while it can be that in the general admission /accident and emergency department you might find only 1 doctor for 30 patients!

[4] Quoted from: S. Guerra, R. Masini, L. Isolabella, E. Santoro, ‘Ipotesi di riassetto sanitario della città di Roma’, Casilina, Roma 1974, p.59. In a survey at the Policlinico from 1974-75 the number of patients was 3,180: in the meantime this number might have come down by another 100?

[5] This ranges from hazards that stem from the type of work, for example the work of radiology workers, who engaged in a struggle around this issue in the winter of 1973, to those that are due to the conditions of overexploitation in which the subcontracted workers are kept. These conditions are often found amongst cleaners, maintenance and kitchen workers etc. The question of radiology is also clearly explained to the patients themselves: “The workers make clear that they are no longer willing to suffer the exploitation of a type of work that is in itself harmful, not only for themselves, but also for the patients, who often suffer the incompetence of those who put their hands under the x-rays, while the radiographer presses a button from a distance […] There are many cases where the detected exposure to radiation is too high.” This is followed by an example of a radiation certificate of an imaging porter (leaflet 10th of March 1973, signed by ‘Workers of the Radiology’).

[6] The bonus payments for night-shifts and hazardous work tasks are paid out of a special fund of the university.

[7] The law 1125 from the 3rd of November 1961 even stated that “in order to be employed within the job category III of a nurse, the possession of a diploma is not required […] provided that the performed labour is recognised as commendable”.

[8] These workers often wait for several hours, till the end of a shift, in order to be given work. For them, of course, there are no paid bank holidays, sick pay and so on. It is enough to be sick for a day and unable to come to the HR office in order to lose even this fragile connection with the hospital. At the end of the month they are paid for the days that they have worked.

[9] And the higher their profit margins, the more they try not only to cure, but also to offer a hotel-like comfort, which is a question of prestige pure and simple. You can take the disproportionate importance of obstetrics departments in the private clinics as an example, in particular in the South. To give birth in luxury is in fact one of the most important status symbols of the southern bourgeoisie, who, as everyone knows, attribute a lot of importance to motherhood.

[10] This doesn’t mean that, also in the relation with the bourgeois patient, the doctor would not use their own knowledge in an exclusive manner, but they use it at their service, like the bourgeois who would supply the doctor with their own goods or a different kind of service. The bourgeoisie, in their mutual relationship, understand the class motives in their reciprocal ‘exclusivity’ and don’t feel regret about it. A lawyer or an engineer would not like to share their own knowledge with a doctor when representing him in a court case, or build him a house, in the same way that the doctor does not impart his own knowledge when they fall ill.

[11] From a leaflet of the Assembly of the Workers at the Policlinico, from the 24th of June 1974.

[12] Being part of SUNPU was seen as a factual membership of CGIL, even though on paper one was a member of the three union federations. The unions of non-teaching university staff divided up their zones of influence: while the CGIL was only present in the clinics, CISL and UIL represented staff in the actual university. (5th of June 1972)

[13] For example the law no. 1225 of the 3rd of November 1961 prescribes the job transfer of those precarious workers who have been hired after the 1st of June 1961; the law of the 28th of February 1970 prescribes the job transfer of those hired after the 31st of July 1970. As these laws give these workers a supernumerary status, who wait for posts to become free, they are only a halfway solution, because initially they block actual career advancement.

[14] In certain cases the union acts as a real state structure, for example when it collects applications for internal vacancies in competition with the university secretariat and afterwards tries to have ‘their’ applicants hired.

[15] In this way SUNPU rescued its raison d’etre: if the workers in the clinics weren’t state employees, but employed by the hospital, SUNPU would not exist. When the workers of the clinics proposed to push for a transfer to the hospital contract, SUNPU tried everything to obstruct this, backed by the union federation Federstatali (to which it belonged).The Collective of Workers and Students at the Policlinico (11th of November 1971) stressed that this obstructive behaviour, apart from showing that SUNPU ‘prioritises’ its own interests to a real unity of workers, reveals the fear of the Federstatali to not only lose a lot of members, but also the only workers who, through their struggles, bestowed it with credibility. In fact, the workers of the clinics have always expressed a high level of combativeness, in spite of the attitude of the union leadership.

[16] The Collective of Medicine had also always been a stronghold of Manifesto in Rome.

[17] Later on this attitude transformed itself into an action that was diametrically opposed to the one of the Collective of the Policlinico, even when the solidarity of the students was openly requested. In March 1972, during the course of a struggle against the precarious contracts during which it came to the first internal protest march autonomously organised by the Collective, the hope was that students, hospital and university workers would participate actively in the demonstration against the contracts. “This didn’t happen! […] The hospital and university workers, who were traumatised for too many years by the reformist conditioning of the trade union, were not able to easily do away with the firefighting role of the union activists, while the medical students, in contempt for the proclaimed effort to create a unity with the workers, remained passive and subordinated their action to the institutional terrain of dealings between trade union structures” (10th of March 1972). This boycott repeated itself subsequently during the course of the struggle for the transfer of the hospital from university to the public health administration.

[18] 2nd of March 1972 – One has also to keep in mind that on the terrain of social struggles, revisionism is more absent, and that this is a fundamental part of the emergence of many autonomous struggles.

[19] Of course we have to consider that in the worker’s consciousness the problem is often still perceived in its mystified form: it is a daily occurrence to hear workers say that they feel physically bad because they have not taken care or because they are “nervous”. Workers become subjects in this struggle to the extent that their revolutionary consciousness grows and with it their capacity to criticise the revisionist line put forward by the trade union.

[20] In the leaflet of the Collective of the Policlinico from the 24th of July 1974 a photocopy of a declaration is documented, which had been signed by a group of patients on the 17th of July, in which they state that “they have paid 50,000 Lire to Prof. Aldo Turchetti and that they have subsequently been treated immediately in the medical clinic no.1 directly by him”. This is one of many examples which would come to light during the course of the struggle.

[21] Therefore it is neither true – as claimed by some comrades – that the auxiliary nurse is a proletarian who struggles against a routinised work, like they do at the assembly line: because the material with which they work is another human being, another proletarian. The struggle against their alienated conditions has therefore to take into account the necessity to join up with the patients. What workers said in the quoted leaflets will be examined further in the text.

[22] “We have to turn the hospital into a space where the contents of the struggle against toxic working conditions are being circulated in order to come to a unity of struggle for common objectives, in order to destroy the current structure of the hospital and use it not for readjustments and reintegration into the productive cycle, but to create a consciousness amongst ever more vast strata of workers about the close relation between exploitation and illness” (2nd of March 1972)

[23] In reality, in none of the two cases is the term ‘exploitation’ correct. Regarding the worker, in public hospitals no surplus value is extracted, but rather the state spends here the surplus value created by workers in factories. Neither do the patients produce a surplus value, because they are not active instruments in the hands of the barons, but they are rather inert material that they ‘exploit’ like a raw material. Nevertheless, we continue using these expressions used by the collective because they highlight the antagonism that exists between workers and barons and between patients and barons, and they also help to locate the class enemy inside of public institutions.