We translated an article on the history of the workers’ collective at the polyclinic in Rome and added subtitles to an inspiring documentary. The original of this report on the hospital ward occupation can be found here.

A first reflection

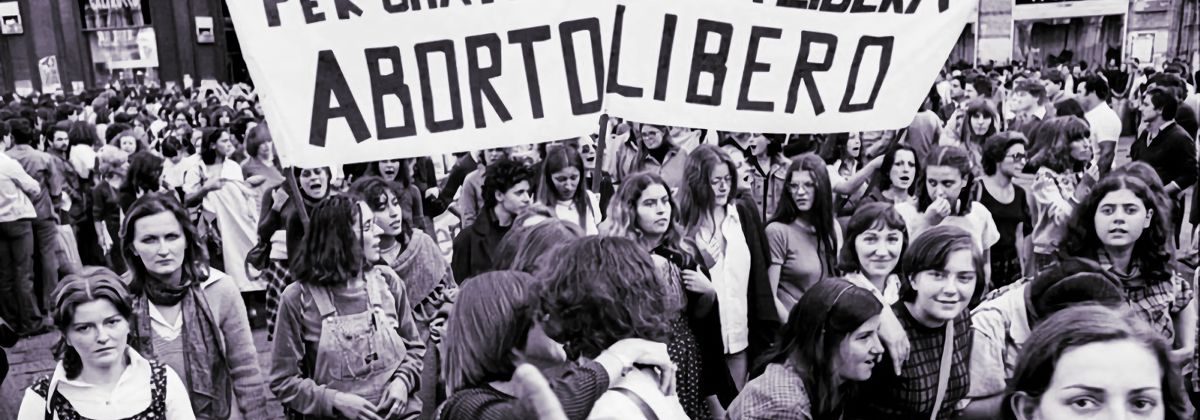

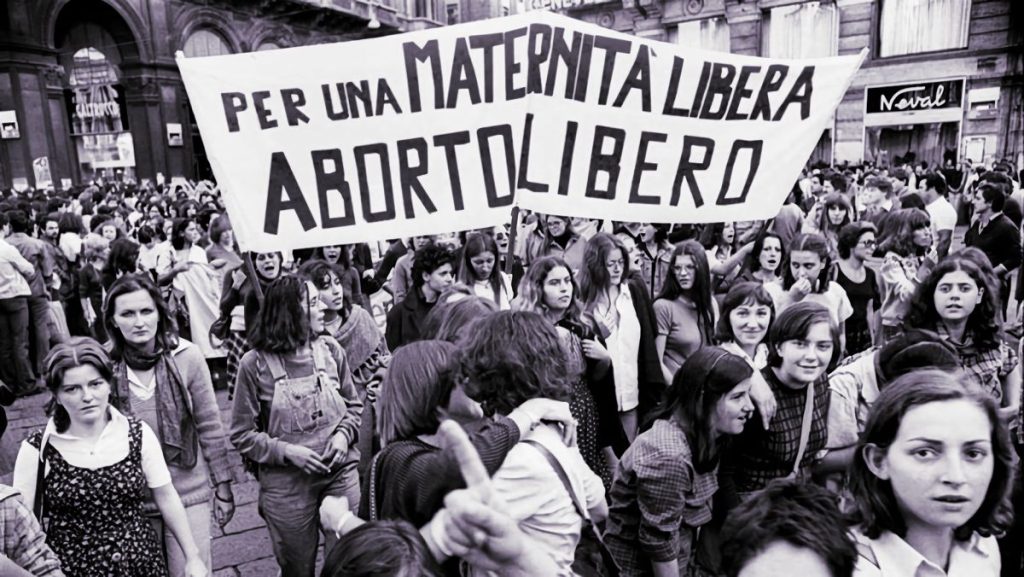

After the passing of the abortion law, the (female) comrades of the San Lorenzo Collective in Rome chose the Policlinico as a moment of verification and continuity of their experience of the ‘nuclei for the self-management of abortions’. They chose the clinic both for its proximity and for the presence of a situation of struggle that guaranteed a minimum of self-organisation. The occupation of a ward of the Policlinico reactivated for abortions was the most advanced experience of struggle in a public health facility in Rome. After three months, the ward was ‘cleared’ with a police operation; ‘their’ (the cops) occupation still lasts. The (female) comrades have begun a collective reflection on this experience and have collected their testimonies, with complete documentation, in a small book soon to be published. We feel it is important to let those of us who are personally involved in making sure that the law is properly applied in the hospitals and all of us women whose rights were recognised and immediately taken away know about the nature and complexity of the problems that arose from this experience.

Silvia of the S. Lorenzo Collective in Rome – December 1978

After three months of ‘feminist occupation’, the ward of the Policlinico that was reactivated for abortions was returned to normal through a police operation. This means several things:

First of all, the reaffirmation of a technical power of the medical class over the paramedic staff and patients, and above all over women; a power that cannot be undermined without calling into question behaviours that are also political: just think of how acceptance normally takes place, of all the steps that one goes through in the hospital before and after the operating theatre. The will to reaffirm – even with the presence of public force – the untouchability of this power, that entrenches itself behind the possession of a scientific training and specialisation completely controlled by a closed and corporate professional order, was very clear.

Secondly, the unconditional support of the political forces that govern local administration for the power structures existing in public and private health facilities; these powers are based on co-option, on clientele (sometimes of a mafia type) and on the maintenance of the psychological subalternity of the people who are part of the medical category at various levels: their subalternity is paid for with various types of privileges and through psychological rewards, recognised to those who possess knowledge and know how to use it to their own advantage and in the most convenient way for the category that controls it. It certainly seems difficult to fight against centres of power that are never isolated from each other, but rather intertwined with each other, with party leaderships and with interests in other sectors (including industry and educated culture).

Thirdly, an application of the law on abortion that in practice grants no possibility of direct initiative to women. It is no coincidence that those who drafted the law adhered to a general rule that social subjects who are impacted on by these measures should be controllable; control is imposed through normal administrative action. In fact, self-determination has been formally recognised, but care has been taken not to create the possibility for women’s groups to really affect the functioning of the institutions called upon to ‘serve’ them. Self-determination is recognised as a merely individual possibility; moreover, it is denied de facto at every step of the law by a framework of bureaucratic steps that reiterates, for those who have not yet understood, that the state protects motherhood and safeguards women and children. Thus, with the support of an ambiguous and generic law, the health facilities and the few existing consultancies are already demonstrating what this possibility of state control means, which not only tends to blunt women’s demands by atomising them, but is already being used specifically to prevent them from being enforced collectively.

The operation of counselling centres has already taught us something about this. The rigmarole of obtaining the certificate permitting abortion serves, by itself, to clarify certain written and unwritten rules governing the relationship of the user – particularly the woman user – with the institutions. If she is lucky enough to overcome the barriers to being accepted and admitted to a hospital or clinic, the woman then finds herself completely at the mercy of this structure. Thus, to the psychological burden of the humiliating initial rigmarole is added the physical risk: the needs that are taken into account are certainly not those of the person using the service, but those of the organisation that runs it, that is, of the people who operate within it exercising power. Even if the physical risk can be reduced by better equipment, by a more capable doctor than another, living this experience alone becomes traumatic precisely because the moment of abortion brings conflicts and anxieties that have behind them the whole web of relationships with the ‘male’; the impact with an institution such as the hospital is so hard that it is generally removed from consciousness; ‘forgotten’; it is only the relationship with other women, experienced at this moment, that helps to find the thread of an awareness (and not mere consolation). Faced with the first attempts at collective awareness, left-wing parties and organisations behave like watchdogs of the power wielded over women, limiting themselves to pressing for hospitals to equip themselves to perform an adequate number of abortions; for the timing, methods, and conditions of the intervention, women should rely on those who know more than they do, i.e. hospital management and doctors.

Participatory strategies

All this takes place in an increasingly repressive political framework, where the left suffers or even supports the isolation and crushing of all its elements that resist participatory strategies, which are strategies that promote the participation in institutions of those who are in power. The PCI has become a champion of normalisation. In hospitals, as everywhere, it seeks to re-found hierarchies based on a power that has been repainted with technicality. It makes use of a quantity of new legal norms that in theory are intended to account for what goes on in the institutions; in practice they are an arsenal of weapons that can be used to keep up well-established privileges and to marginalise, co-opt and control. Thus normality becomes a cage to keep out the different. It seems unthinkable that, at a time when the call to order is so strong, women – these ‘different’ ones par excellence – really question cultural and scientific values on which a whole complex system of relations and powers rests.

The left-wing parties adopt soft tactics towards feminists that serve to painlessly absorb what is most vital and stimulating about the movement: this is evident in publishing, the press, the mass media in general. As usual, the operation seeks to establish itself by means of awards given to ‘good’ women on an individual basis. Even in political life, women function as a tonic, they are new subjects: accepted as long as they do not really undermine the massive male values present in all life situations and consciences. If women claim to stand up for their needs collectively, impacting on the reality of power, their friends on the left will judge that the ‘good’ must be divided from the ‘bad’. Precisely this has happened in the abortion struggle. The left paternalistically praises the participatory drive that women know how to express in order to enforce the law; with their protests against institutions, they show that they know how to impart new impulses to political life. But repression strikes immediately when the ‘new subjects’ seriously believe they can counter the command exercised over them.

After the occupation of the ward at the Policlinico, the health and regional authorities, the parties, pretended to use the affair as a case of positive intervention by women, which had unblocked the immobility of a hospital degraded by the conservative party, DC. This happened when everyone had by then realised that the occupation had been led by women and not by a few males from the Autonomia (although some still harbour doubts). After the ward was restarted, even the doctors showered the feminists with praise: ‘Bravo! Thanks to them, the ward would from now on start working again.’ But at this point, they sent them home unceremoniously, because they were beginning to become intruders. And since the expulsion was not accepted so easily, they tried to divide the women, denouncing the dirty alliance between the feminists and the women of the Policlinico Collective, the only organised group that, although different from the feminists, immediately set about enforcing the law in the hospital.

The denunciation of this alliance is purely instrumental: in fact, our friends who want to bring us back to order – Unità in the lead – avoid talking about a particular fact: the women comrades of the Policlinico Collective were present with us in the ward as women and were the first to confront the health institution from within at the dramatic moment of the application of the abortion law. As usual, there is an attempt to play the political game over women’s bodies; because, as was immediately clear, the target that is attacked is precisely the emergence of initiatives that appropriate control from the parties that govern the health institution. Women’s health is entirely secondary in this game.

In order to reaffirm the full control of the doctors and politicians (each other’s watchdogs), the ‘good’ feminists were even offered the content of a symbolic presence – secured by four or five female comrades who could have returned to the ward – for who knows what reason. Of course it would be appreciated if they would continue to perform free labour, which can always be useful, after having duly distanced themselves from the Polyclinic Collective. Here’s the point: women are accepted because they work hard, as long as they don’t annoy too much; if they no longer accept to behave ‘like women’, all the male counterparts simply go berserk.

The struggle has opened up a number of problems that many would like to bury as quickly as possible. The thorniest one concerns work. The lovers of order complained loudly about the ‘squatters’ being on the ‘struggle list’, which would allow them to be considered during future recruitment for hospital jobs. They tried hard to censor the real problems behind the presence of women who work as volunteers in the department, and behind the demand to be hired. Instead they said other things, such as that the squatters were a means of dividing the workers already on the ‘struggle list’ within the wider Polyclinic, and so on. Of course, they could not admit the fact that the female comrades tried to stay on the ward for two specific reasons: a) because they did not like unpaid work, b) because their presence was the only real guarantee for the women because to the female comrades the question of who is in control and how is this control exercised was so dear to them. With women being present, things would come out that were embarrassing to handle. And then, the women comrades were in the department claiming not only to work, but to do it in a certain way, and even that is not a problem that can be easily dismissed .

What is our relationship with the institutions?

During the occupation of the Polyclinic, we tried to control what was happening inside the institution through work done by comrades who worked inside, either as volunteers or as hospital employees. This was important for the quality of the control we tried to exercise, but it also raised several problems for us. Work, voluntary or otherwise, is all up for discussion among the women comrades: what does it mean to work in an institution, trying to politicise one’s professional role (e.g. that of female doctor, nurse, midwife, porter), and what does unpaid self-managed work entail? Furthermore, how can the motivations of these struggles be welded to those of those who ‘transit’ into institutions as users? And how can the movement support these struggles? On these issues we would like to move forward, not back. The Policlinico struggle was taking on specific forms precisely in the positive affirmation of contents concerning health work; themes already present in the Policlinico Collective were being developed, but also others of their own, linked for example to self-help [original in English].

There was, in common with the Collective, the desire not to be opponents of women who came for abortions, but the opposition to medical power. But the desire to start from the needs of women and the experience of self-help led us to attempt a form of self-management that tended to undermine the technical and decision-making power of the doctors, and not just denounce it. The experience of the occupied ward went, in this sense, beyond the threshold bearable by a health institution and our own organisational capacity. Rather than proposing it as a model that is immediately sustainable in the long term, we should consider it for all that it meant in the limited time of its duration: it was an experience that made us verify for the first time the practical consequences that listening to our needs can have in the health organisation: if one listens to these needs, without subordinating them to conditions set by others, the normal health organisation undergoes upheaval, it is called into question from top to bottom. Our struggle was not only about problems of hierarchies and pay, but also decisively expressed a desire for the re-appropriation of knowledge by subordinate women workers vis-à-vis doctors; and what is more, it presupposed a socialisation of knowledge between the women worker comrades on the ward and the women who came for abortions. The physical occupation of the ward, or the interruption of the normal routine of the hospital, could not have expressed its contents without being accompanied by a complex interaction with the doctors, with their knowledge. That is why it is absurd to interpret the content of this struggle only in terms of claiming the job, or as a replacement or adjustment action for the shortcomings of the institution.

There was, then, a close relationship with the women who came for abortions, but also some ambiguity: in fact, the institution is always a ‘counterpart’, which the user identifies in the people with whom she is in fact confronted. Experiencing a ‘hot’ moment in the struggle resulted in a welding together of volunteer workers, nurses, feminists on the ward and women who had to undergo the operation. But perhaps we cannot always rely solely on the guarantees created by a situation in motion; there may be different moments, when our control is not as incisive, but more external, when our mobilisation is more sluggish, and how should we organise ourselves in view of this? Can we propose that we systematically enter the institutions together with the women users, to experience the stages of hospitalisation alongside them, to control (even when we are not employees of the hospital or clinic) what the doctors do? Must the struggle of women outside the institution, who want to control what goes on inside, always be linked with that of women workers, and in what way? And is it possible that it presents different or complementary ways of organising?

Certainly, collective actions re-propose the crucial issue of organisation. Even if complete self-management is not feasible and will not be for a long time, neither inside nor outside institutions, we cannot avoid asking ourselves the question, if control really interests us. And here, the confrontation not only comes out violently with external reality, but with our own conflicts, between desires on the one hand and the needs of technology and division of labour on the other. To respond by escaping into the ‘private’ is a bit like accepting the delegation to political organisations, accepting the limits placed by male politics on our struggles, and it is a big risk for us. It means, in fact, being divided, as a natural consequence of social organisation, between the guaranteed and the non-guaranteed, between women who are included – even if in a subordinate way – in some hierarchy of privilege in terms of work, politics, material conditions of existence, and women with whom it is difficult to find points of solidarity, because they are more marginalised than the others. Each of us knows that, on her own, she cannot fully combat her exploitation but only seek spaces to live better, to be less oppressed. This seems, for now, to be the only way out, given the long time the movement has to travel in the search for goals that go beyond what has been achieved so far. There are different forms of alienation and subalternity, exploitation that each one suffers, and it will take time to discover and connect them.

In the meantime, our collective weakness strengthens the state; that is, the people who make us give birth in conditions that are sometimes worse than two thousand years ago; who make us instruments of domestic labour, in the various forms of recognised and unpaid labour. This instrumentality is not purely physical, but also psychic. We begin to move away from the fatalistic acceptance of the inferior relationship with those who control our lives, realising that the isolation suffered in one situation, is the extension of other situations of oppression that follow one another in our lives. The hospital, precisely, is a public service that we use in solitude. The woman who faces abortion, childbirth, is isolated in traumatic moments of her life, as she is in any kind of hospitalisation, especially when she does not present herself as a special or privileged client. The normal functioning of the institution is oppressive for her, whether in dilapidated hospitals or well-equipped clinics. The oppression stems, in the first place, from the total impossibility of controlling what is practised on her body. But under what conditions could we intervene to control?

The lack of collective ‘strategies’ weighs on the comrades who have started to attack some institutional realities. Isolation can bring back questions that were present in these experiences. Should we give up trying to answer them? Or should we accept the political advice of those who insist on limiting our intervention to an external control – not sure how incisive, unless it really calls into question the technicians and their knowledge? Should we trust the doctors, whose level of political consciousness goes so far as to allow women to serve them so that they can better exercise their profession, or perhaps to delegate some subordinate function to women, but not to accept that women should fight themselves to pave the way for different values, for ways of practising medicine that would undermine the institution and with it their own power?

We do not believe, on the other hand, that the political engagement between women can any longer be separated from collectively experienced situations, and analysed within the context of everyday life. That is why demonstrations in the streets are no longer enough for us, but we would like to fight on the terrain of everyday existence. In this way, perhaps, the needs of everyone can begin to be expressed.