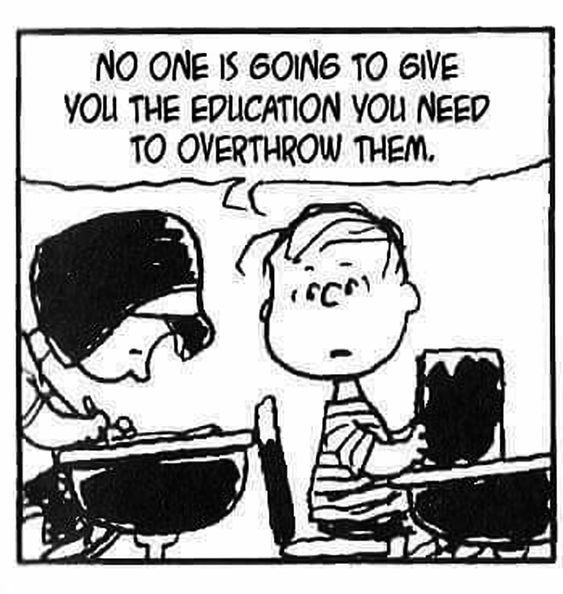

A manual for building worker power in the education industry

We document this text by Angry Education Workers from the USA

Adapted from Karl Marx’s pamphlet “A Workers’ Inquiry”, first published in La Revue socialiste, April 20, 1880; Transcribed by Curtis Price, 1997. Full text available here

Who are we?

We are a political art collective of radical education workers based in the DC, MD, VA (DMV) region of the United States. Our goal is to become a node in the wider class struggle that creates overlap with other like-minded organizations, communities, and individuals—while remaining rooted in our workplaces. To accomplish this, we aim to open up as much dialogue between education workers of all kinds as possible. Big businesses and the state can take advantage of mainstream methods of mass communication like advertisements, the news media, and social media algorithms to shape narratives to their own ends. But we have our own. Internationalism and anti-imperialism thus form bedrock principles of our collective. Zines, an online newsletter, podcasts, and agitprop such as stickers and fliers are the means to our ends. In the near future, we will be able to distribute these in bigger numbers.

Every education worker plays a vital role in our communities. Yet, the education system divides us, preventing us from organizing together over our shared material interests. Mainstream union leaderships often uphold these divisions, separating workers at the same institution into different bargaining units that compete for measly benefits and fail to support each other during labor actions.

This leaves these mainstream unions often paralyzed in the face of neoliberal capital—which is international in scale—that easily skirts around these arbitrary divisions. We want to chart a different path.

If you’re interested in joining the collective, contact us using the information at the end of this article. We welcome all levels of engagement and involvement. If you want to send us a scribbling about your workplace, a random sticker design, or other agitprop and never submit another piece, that’s fine. Burnout culture is bullshit. All our zines and materials are marked as collectively authored. Even if just one or two people work on a particular piece. This recognizes the fact that individual “authorship” is artificial in the first place. It also protects our jobs and privacy.

We’re especially interested in:

- Investigations of education businesses, foundations, and “non-profits”.

- Worker narratives from current or former workplaces.

- Descriptions of educational institutions, including the composition of the workforce and the history of class struggle at the site.

- Analysis of your local political and legal landscape of the industry.

- Workplace journal entries.

- Thoughts on revolutionary strategy for education workers.

Any identifying information will be removed.

Priority goes to DMV education workers, but we accept submissions from workers everywhere. We want to build contacts between education workers across the industry and around the world. We also encourage you to start your own local collectives by and for workers rooted in education or another specific industry. Feel free to use our project as a “template”, so to speak.

Inquiry by and for Workers

Building power with your coworkers is no walk in the park. It’s more like being in a secret, underground organization. Whether your goal is to build a formal workplace union or not, the bosses don’t respond kindly to any collective resistance by workers. Before you can think of going on the offensive against your shitty boss, you (and your coworkers) need to understand how they exploit you. That means asking and answering substantive questions about your workplace—we recommend keeping a notebook where you can keep track of all this. Don’t let it fall into the wrong hands.

One of the most important sets of information to obtain sounds much simpler than it actually is: finding out who works with you. Capitalism brings together huge numbers of people from all backgrounds to work together to generate profits for the bosses and politicians. Fifteen million people work in the education industry, for example. Only healthcare makes up a larger share of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

But that doesn’t mean your bosses want you to cooperate outside their direct supervision. Most of the time, your bosses can’t actually maintain this level of active surveillance. They’re too fond of their offices. That’s why they’re so careful to keep tight control over information about the workplace within those offices. We’re separated and divided by department, job role, education level, shift, job site, and status. And we can’t check our racial, religious, gender, political, or cultural differences at the door, either. Our bosses rely on that.

The corporate and small business owners tremble before the dangers which an impartial and systematic investigation by and for education workers might represent. Knowledge generated by and for ourselves gives us tangible ways to formulate concrete next steps for building solidarity between you and your coworkers of all backgrounds. This is how we can change the balance of power in our workplaces. Let us subject our workplaces and local economies to a ruthless criticism. That means understanding the negative impacts of our institutions alongside the positive contributions they make. First, we must build relationships with our coworkers and study our jobs through a scientific lens.

We must attempt to initiate an inquiry of this kind with those poor resources which are at our disposal. We hope to meet in this work with the support of all fellow workers in education: urban and rural; manual and intellectual. It is us alone who can describe with full knowledge the misfortunes we suffer. Only we—not experts like education researchers, academics, and journalists, or bureaucrats from government agencies—can begin to heal the social ills which we and our communities are prey to. We also rely upon ideological socialists of all schools who, being wishful for social revolution, must wish for an exact and positive knowledge of the conditions in which the working class—the class to whom the future belongs—works and moves. Margaret Haley eloquently summarized why in her 1904 speech to the National Education Association convention titled “Why Teachers Should Organize”:

Two ideals are struggling for supremacy in American life today: one is the industrial ideal dominating through the supremacy of commercialism, which subordinates the worker to the product and the machine; the other, the ideal of democracy, the ideal of the educators, which places humanity above all machines, and demands that all activity shall be the expression of life. If this ideal of the educators cannot be carried over into the industrial field then the ideal of industrialism will be carried over into the school. Those two ideals can no more continue to exist in American life than our nation could have continued half slave and half free. If the school cannot bring joy to the work of the world, the joy must go out of its own life, and work in the school, as in the industrial field, will become drudgery..

It will be well indeed if the teachers have the courage of their convictions and face all that the labor unions have faced with the same courage and perseverance.

Our self-knowledge and understanding builds solidarity and demystifies the ways our enemies, the bosses, exploit our labor and steal our time. By doing so, we take the forms of organization imposed on us by our bosses and start to build our own structures in the workplace. The goal must be to take control of the schools, libraries, museums, and archives. We also encourage you to share the information you and your coworkers discover with an organizer. Only by communicating across job sites, companies, and districts can we come to a true accounting of the common struggles, demands, and dreams we share as a class of workers in the education industry. This text itself is the product of extensive conversation and revision by several education workers who are actively organizing collective worker power in their workplaces. Some in the collective, and some are not.

Education workers globally are consistently on the front lines of the class struggle. From Hungary, to Mexico, to Russia, to India, and beyond we can build an international movement to beat back privatization and make education truly public. Educational institutions belong to the workers and communities who give them life!

The League of Black Revolutionary Workers in 1960s and 1970s Detroit demonstrated how this can build worker power. At the time, Black workers in the city were building Revolutionary Union Movements (RUMs) in individual factories. Almost all of them published one or more newspapers. Workers discovered they only knew what was going on in their own, individual factories. Newspapers by and for autoworkers broke down those barriers. The Angry Workers political collective in the UK and the Virginia Worker in the US have further tested this idea of the worker run newspaper. In 2006, teacher unionists and community members expropriated not just the schools, but most of the radio and television stations in the Mexican state of Oaxaca. Just last year, teachers and dockworkers took control of a shuttered school in Oakland, CA. Further back, in the 1800s and early 1900s, local newspapers written and published by working class people filled urban neighborhoods. Being able to research with our own tools and speak with our own voices is a revolutionary act.

This manual is meant to help you with your own self-inquiry. We recommend that you start talking to your coworkers about issues at work and use these questions. There are further trainings offered by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) rank-and-file union about how to approach and execute these conversations. They happen often, but not constantly. In the meantime, try to keep conversations with coworkers one on one. Staff lounges and classrooms often work, but ideally have them outside work, even if it’s virtual or over the phone. Once you have a group of coworkers meeting regularly to discuss solving problems with collective action, you can pose the relevant questions to the committee. That way, you can collaborate to answer questions you may not have thought of by yourself. Or add fuller data and discover new ways of thinking about the issues.

Only answer the questions relevant to you. You don’t have to answer all the questions. Or answer them at the same time. Skip and return to them as best for you. Answer in as much or as little detail as you like. If you write eight pages in response to one question, so be it. In replies shared with us the number of the corresponding question should be given. With many of these questions, you will have to perform research and investigate in your physical workplace.

The questions are divided into various categories. Some of these are for the different types of workers in the industry. Many of them will overlap, however. For example, the question about grants and funding posed about schools could easily be applied to libraries and museums.

If you wish to share a summary of the results (so far) of your own worker inquiry, please send them to angryeducationworkers@gmail.com. Don’t worry if you feel your inquiry is incomplete or lacks polish, we appreciate any effort you can make to help workers across the education industry understand their predicaments and how to respond to them.

Replies that you share with us will remain anonymous and undisclosed unless you give us explicit permission otherwise.

Guiding Questions

General Questions

- What is your job role?

- Where do you work? What city? What neighborhood?

- Do you work in a school, museum, library, or archive?

- Are you classified as support staff? (custodians, security guards, maintenance, grounds keeping, dedicated aide, behavior intervention, etc.)

- What is the age, gender, racial, religious, etc composition of the workforce? Gather a full list of your coworkers and their non-work contact information. A spreadsheet is a great way to keep track of this information.

- Is there sufficient work for your existence or are you forced to combine it with a second or third job? If you have another job, what is it? When do you work it?

- Do you work with your hands, head, or with the help of machinery? All three?

- How many employees are there?

- State the number of administrators and other employees who are not rank-and-file hired workers.

- Which rank-and-file employees have close relationships with management/administration?

- Are you a worker in the building from staffing agencies or on other forms of contract/temporary employment? Has your number grown in your institution since the start of the pandemic?

- How much time do you lose in your commute? How do you get to work? Can you afford to live in the community you serve? If yes, do you struggle to afford it?

- What are the general physical, intellectual and moral conditions of life of the working people employed in your trade or industry?

- If you work at home, describe the conditions of your work room. Do you use working tools or computers? Do you have recourse to the help of your children or other persons? Do you work for private clients, or for an employer? Do you deal with them direct or through an agent?

- Is Information Technology (IT) staff employed on-site, or are they contracted out? Is there a management company that employs them directly instead?

- Compare the price of the commodities you manufacture or the services you render with your pay. For example, in Washington D.C., each general education student comes with $24,000 in public funds. Special education students $31,000. In the 2023-2024 school year these figures will each increase by 5 percent. Most school staff, especially instructional staff, labor on dozens of students at a time every day. With just 50 students, a classroom teacher in the District is helping produce $1.2 million in human capital. Divide by 180—the usual minimal number of instructional days—and you discover that the average teacher produces more than $6,000 of human capital every day. Their starting annual pay rarely exceeds $60,000 (a daily wage of maybe $300), and even highly experienced teachers max out at $90,000 in a city with one of the highest costs of living in the country. Most teachers around the country make significantly less since DC has the 4th highest teacher pay in the entire United States. Many other school staff members make even less.

Questions for and about Support Staff

- If you are support staff at a school, library, or museum, how would you describe the relationship between support and instructional staff?

- Does administration treat you differently from instructional staff?

- If work takes place both night and day, what is the order of the shifts? Is there any communication between them?

- Is there mandatory or voluntary overtime offered? Do overtime hours fluctuate based on season?

- Are any support staff contracted out or hired directly by the institution you work for?

- If you are a crossing guard, what personal dangers do you face from traffic? Do you normally work in another role?

- How is student transportation and busing handled? Where are buses parked? Where are they taken for maintenance and gas?

- Do you receive the same visibility and recognition that instructional staff receive from the institution?

- What is the turnover rate for support staff compared to instructional staff?

- Are there on site maintenance staff or are you hired from outside?

Questions for and about School Workers

- If you work in a school: Is your educational workplace part of a traditional public school district? Or do you work in a charter, private, or alternative school situation?

- If you work in a charter school: Is your school managed by a major Charter Management Organization (CMO) like KIPP? A local charter school network? Is there a site-specific school board?

- Who is on the school board? What are their connections to corporations, government bodies, or potentially unaccountable foundations?

- What age range/grade levels do you work with?

- Who is on the district/state boards of education? Is there a separate school board overseeing charter schools? Who is on it?

- Who are the institution’s donors? Does the school rely on grants to keep certain programs running?

- Are their volunteers, interns, student teachers? How many? Does Teach for America have any people placed in the building?

- Does your school help with purchasing supplies? Do you ever have to spend your own money on classroom supplies? If yes, how much?

- How many SPED workers are in your school? Is this amount enough to effectively and caringly manage their caseloads?

- How often do you, as a mandated reporter under the law, file reports in cases where you suspect child abuse or neglect? Have you ever refrained from filing because there are so many cases where you suspect abuse or neglect? Have you ever refrained because you felt Child Protective Services response would inflict further harm on the child?

- If you are a substitute, classroom teacher, or another type of school worker forced to cover extra classes, are you supposed to be paid for that work? Is there a clear way of documenting the labor time you put in? Do payments actually come through?

- How does your pay compare with other substitute teachers and teachers who are not substitutes?

- How many classroom teachers and other instructional staff are certified?

- What curriculum does your school use?

- Where does the curriculum come from?

- If you work in a school as a teacher, do you have control over what you teach? Is there a scripted curriculum you must follow? Autonomy without curricular support from the school? Are there differences by subject?

- If there is a scripted curriculum, do teachers follow it?

- How are the students fed? What companies does the school institution hire/contract with for deliveries? What schedule do they follow?

- What are the policies on printing and copying? How many copy machines are there in the school? How many copies, color and greyscale, are allowed per employee? What company delivers the paper?

- For front office staff: what informal expectations exist for you to maintain the staff culture within the school?

- Does your school have a media center or library? Is there a school librarian employed there?

- Does your school have any counselors on-site?

Questions for and about Post-Secondary Workers

- Do you work for a public or private university or college? A community college system?

- Do you work for a vocational school or program?

- Are you tenured? What are the conditions of your tenure?

- Are you dependent on the post-secondary institution that employs you for housing?

- Are you paid through various stipends and grants?

- If you are instructional staff, what is the ratio of researching versus teaching you are expected to carry out through your workload?

Questions for Preschool and Daycare Workers

- If you work in a daycare/preschool, what are your local laws on child care?

- Do you work under a certified or un-certified daycare/preschool location?

- Is your workplace franchised?

- If you work in a daycare/preschool location that also teaches older students, how are you treated in comparison with colleagues who work with older students?

Questions for and about Library Workers

- If you work in a library: Is it a single branch within a library system in a major urban center? A county library system?

- Is it an academic, special, or public library?

- Do you receive meaningful autonomy in your work? Do you have opportunities to help develop library programming?

- What programming does your library branch offer?

- Do you receive autonomy in designing programming without meaningful decision making power or resources for implementation?

- If you work in a school library, have there been attempts to cut your programs or position?

- How does administration evaluate performance? Do any measures seem arbitrary?

Questions for and about Museum Workers

- How is the museum funded? Does it receive any public funds?

- Does your museum charge for admission? How much?

- What type of museum do you work in?

- What area does your museum serve? Is it a national museum institution like the Smithsonian? Is it a local museum for a town, city, or county?

- What exhibits and programs does your location offer to the public?

Questions for and about the Students and Community Members

- Is there racist, sexist, homophobic, or other bigoted mistreatment of you and your fellow students?

- Do you feel that you are treated as “raw material”? Or that your school structure resembles a factory assembly line?

- Where are the sympathies of the local community? What resources and support could they provide?

- What sympathetic or potentially sympathetic community/civic organizations exist around the institution?

- Which staff members are sympathetic or accomplices to your own causes and struggles?

- How could these resources and people be mobilized?

Questions about the Layout and Structure of the Workplace

- How is the labor divided in your workplace? What departments exist? Do you have access to an organizational chart?

- Where does the electrical power come from?

- When and how are supplies delivered? What companies does the institution contract with?

- How is student drop-off and pickup managed? Is it conducted safely?

- State the number of rooms in which the various branches of production are carried on. Draw a map of the workplace.

- Describe the specialty in which you are engaged. Describe not only the technical side, but the muscular and nervous strain required, and its general effect on the physical and mental health of you and your coworkers.

- Describe the hygienic conditions in the workspace; the size of the rooms, space allotted to every worker and student, ventilation, temperature, plastering, lavatories, general cleanliness, noise of machinery, pollution, dampness, and so on.

- Is there any municipal or government supervision of hygienic conditions in the workplace?

- Are there particular hazards which are harmful for the health and produce specific diseases among the workers?

- Mention the accidents and incidents which have taken place to your personal knowledge.

- Are there sufficient safety appliances against fire?

- Have you ever received hazard pay?

- Is there a nurse or other medical professional employed in your school, library, or museum? If you are such a medical professional, do you have adequate PPE provided? What are the conditions of your work?

Questions about the Raw Material and Relationship with the Public

- If you work in a school, what are student enrollment levels?

- What behavior issues are common among the students?

- Do you feel that the administration ever lets students off the hook when they shouldn’t? Does your administration punish students too harshly?

- How much public and private funding follows each student into the building? See question sixteen for DC figures.

- If you work in a private school, how is admissions handled? Financial aid? Are there inequalities in how they are managed?

- If you work in a charter school, does your school use a lottery system for admissions?

- If you work in a library or museum, how many patrons can you expect daily? What are they like?

- Are there police officers stationed in or around your school, library, museum, or archive? How do patrons, students, and community members feel about their presence? Workers?

- Does the administration force you to implement policies you disagree with?

- Does your administration push or abandon you into dangerous situations with patrons or students?

Questions about Scheduling and Work Hours

- How many hours a day do you work? How many days a week?

- Are you paid hourly or do you receive a salary?

- Do you ever take work home with you, come early, or stay late? Are you paid for these hours?

- Do you work on weekends? Either “voluntarily” or through compulsion?

- How many holiday breaks do you get each year? Has the administration tried to take any away or whittle them down?

- What breaks are there during the working day?

- Do you take meals at definite intervals, or irregularly? Do you eat in the workshop or outside?

- Do you or your coworkers work through meal times?

- Does the institution provide adequate infrastructure for refrigerating and heating meals that workers bring from home? Is water available to staff and students? If so, what do staff and students know about the water quality?

- If you work in a school, when does the school-day begin and end? When are workers expected to come in? Are there differences between departments in requirements?

- If you work in a museum or library: when do you open? When do you close? Do you have to come in before, or stay after, formal open hours of the institution?

- If you are a teacher: Do you receive planning periods? Is there a difference between the time you are allotted and the actual time you are able to spend planning instruction?

Questions about Employment Arrangements and Pay

- What agreements do you have with your employer? Are you engaged by the day, week, month, etc.?

- What conditions are laid down regarding dismissals or leaving employment? Are you at will employed? If you are in the United States, the answer is almost certainly ‘yes’ unless you have an officially certified union at your work.

- Are you paid weekly, biweekly, monthly, or on some other arrangement?

- What are the details of any fringe benefits offered by your employer, if available?

- Has your pay ever been delayed? Have you ever had to go into credit card or other forms of debt as a result?

- How have budget cuts affected the institution in which you work?

- Are wages paid directly by the employer, through the staffing agencies, through some other means?

- If wages are paid by contractors or other intermediaries, what are the conditions of your contract?

- What is the amount of your money wages by the day? The week? The month? The year?

- What are the wages of the most marginalized workers in your shop?

- What was the highest daily wage last month in your shop?

- What were your own wages during the same time, and if you have a family, what were the wages of your partner and children? Does your partner make less, the same, or significantly more than you?

- Are wages paid entirely in money, or in some other form? Does your boss/administration ever throw pizza parties or similar events?

- What are the prices of necessary commodities? A cost of living calculator (search “cost of living calculator” and you will find plenty of options) is an easy method of getting an approximate sense of price levels in your area.

- Try and draw up a weekly, monthly, and yearly budget of your income and expenditure for self and family. Have you noticed, in your personal experience, a bigger rise in the price of immediate necessities, e.g., rent, food, etc., than in wages?

- What are the salaries of upper management/administration? What bonuses and extra benefits do they seem to receive?

- Many education technology (edtech) companies, including communication platforms and providers of digital assessments, claim that they make educators jobs easier. How true is that in your experience?

- Many edtech companies also claim that their products help educators become more productive. How true is that for you? If you have become more productive, have you or any other rank-and-file workers received any raises as a result?

- Have you noticed, in your personal experience, a bigger rise in the price of immediate necessities, e.g., rent, food, etc., than in wages?

- State the changes in wages which you know of.

- Have there been any pay raises in your workplace? Do they match up with rises in inflation/prices?

- Describe any interruptions in employment caused by changes in fashions and partial and general crises like Covid-19. Describe your own involuntary unemployment.

- Have you ever known any rank-and-file workers who could retire from employment at the age of 65 and live on the money earned by them as wage workers. Are there any workers who have come out of retirement, or never retired after 65, in your workplace?

- How many years can a worker of average health be employed in your job role?

- If you experience any disabilities that affect your daily experience at work in any way, do you receive any of the necessary accommodations?What are the laws on this in your area? What is your pay compared to other workers?

Questions about Resistance and Retaliation in the Workplace

- Quote any cases known to you of workers being driven out from burnout or harassment from administrations.

- Do any resistance associations like unions or political collectives exist in your workplace or education sector and how are they led? Are they formal or informal? How helpful do you find them?

- How many strikes and other direct actions have taken place in your trade or industry that you are aware of?

- How long did these strikes or direct actions last?

- Were they for the object of increasing wages, or were they organized to resist a reduction of wages, or connected with the length of the working day, or prompted by other motives? To resist charter school laws or gentrification? Something else?

- What were their results?

- How have the courts responded to these efforts?

- Were strikes in your trade ever supported by strikes of workers belonging to other trades?

- What—if anything—have employers done to hinder strikes or other organizing efforts? Have they ever created their own associations with the object of lowering wages, lengthening the workday, or generally imposing their own wishes?

- Have the governmental bodies regulating your institution acted to impose policies over the opposition of workers?

- What are the laws on subjects like “Critical Race Theory” in your locality? Have education workers been targeted for speaking on these subjects? Has anyone self-censored in response to these laws? Does anyone flout these laws?

- How hard does the government seem to work to call attention to and enforce laws and regulations restricting workers? What about compared to how hard they work to call attention to and enforce rules and regulations designed to restrict employers and empower workers?

- Miscellaneous remarks.

“To change everything, where do you start? Everywhere!…Each their own historian. We’d be more careful about the way we live. Me, you, him, her, them, us, all of you….Class struggle!”

Get in touch / Join us!

Angry Education Workers’ adaptation of this text was first published on our Substack blog on April 20, 2023 to commemorate the 143rd anniversary of Marx’s original pamphlet.

Send responses to the guiding questions, submissions, and suggestions for additions to:

angryeducationworkers@gmail.com

Find everything we do through our linktree!