We’ve translated an excerpt (Interview with Giacomo and Piero Despali, edited by Mimmo Sersante, published by Derive Approdi) of this book, which documents a long interview with two of the participants in the political collectives in the late 1970s. We haven’t translated it because of political nostalgia, but because it deals with the question of how to defend wages and workers’ independent organisation in times of crisis and repression. At the time of the political collective’s life, the large factories were coming under increasing attack and being isolated from the rest of the movement, and the remaining political activity primarily involved small companies, student-workers, workers who worked from home and the unemployed. There are bits and bobs to learn for our situation today. Here we can refer to our recent articles on the ‘Don’t Pay’ campaign, about the current strike wave and the role of workers’ vanguards in the current moment.

The text on the back cover of the book can serve as a brief general introduction to the Political Collectives:

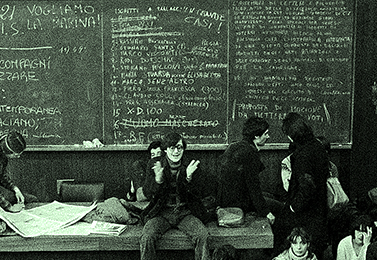

“The story of the political collectives for workers’ power began in autumn 1974, after the experience of Potere Operaio came to an end. The project was founded on an explicit strategy of forming strong territorial roots, of political-military unity of militancy and a trajectory that can lay claim to a rich and refined theoretical-cultural development in the tradition of Operaismo. [1] In this political laboratory, which could make use of a strong presence within the ambit of the university and which comprised a radio (Sherwood) and a magazine (Autonomia), comrades engaged in inquiries and analyses about the contemporary process of productive restructuring. These inquiries would form the concept of the ‘diffuse factory’ that gave life to the ‘social worker’, the figure of the modern precarious worker that would be destined to take on a central role in the political conflicts of the class. Within the vast area of their region, the collectives organised political-military mass actions against the fascists, responsible representatives of the repression and the factory hierarchy for which they were able to count on various groups, each corresponding to a specific level of organisation. The increasing scope of these practices galvanised in the famous ‘night of the fires’, which saw dozens of parallel attacks in various cities of the region. The repressive operations of the 7th of April 1979 [which saw thousands of comrades arrested – the translator], and those in the following years, aimed at the destruction of this organised network and its revolutionary project, which was amongst the strongest, most consolidated and intelligent within the galaxy of autonomy.”

Unlike the political collectives in Porto Marghera or Magneti Marelli, which also emerged from the political ruins of organisations like Lotta Continua and Potere Operaia, but who were mainly industrial workers, the core militants in Padova were students and university workers. They reached out into the industrial zones, and, what is more exceptional, into the working class villages in the region. Their political approach might have clearer flirtations with a certain kind of Maoism, e.g. their territorial strategies of building red bases, and their relation to the PCI seems a bit more blurry than that of their contemporary comrades at Senza Tregua. (For a wider political context of the time please check out our article on Senza Tregua). We will translate further excerpts in the future. We slightly changed the order of the text for chronological reasons. When the comrades mention proletarian rounds they refer to the practice of groups of workers and unemployed to blockade companies that run overtime or to enforce lower prices for public transport or other utilities.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

The year 1976 was crucial for the growth of our collective. There were lots of us, perhaps a thousand in the whole of the Veneto region; a thousand comrades who participated actively for various reasons. It was a crucial year, because the collective contracts were coming up and because of the PCI’s electoral victory. One out of three people in Italy voted for the PCI, but at the same time we should not forget the failure of the electoral alliance Democrazia Proletaria, which had already formed for the regional elections in 1975. The alliance comprised the Unita Proletaria Per Il Communismo, Avanguardia Operaia, Movimenti Dei Lavoratori Per Il Socialismo; Lotta Continua joined it in 1976. Together with other minoritarian formations, it was no more than a platform that gathered 1.52% of the votes and six elected representatives in parliament. A failure in all regards. The result confirmed our belief that there was no space to the left of the PCI in an electoral competition, and that a vote for this party could have sharpened the contradiction between its two souls, the soul of the government and the soul of struggle. It didn’t take long for the chickens to come home to roost with the formation of the first government of national unity led by the conservative Aldo Moro, supported by Enrico Berlinguer from the PCI.

In the face of all this, it became a priority to re-start our political initiatives around some main issues of our program in the factories and the territory with even more vigor and determination. For example we confronted the issue of overtime work head on, which, together with redundancies, had become another weapon of the bosses to enforce restructuring and decentralisation. While our worker comrades had to work the entire week, including Saturdays and regular double-shifts, the trade union appeared impotent, if not outright complicit. Often they accepted overtime, double-shifts and the intensification of the pace of work in exchange for some puny pay hikes. In 1976, in particular in upper Padovana, where the Collective North was active, we noticed the first signals of attacks from the trade union against us, which meant that the practice of proletarian rounds and pickets hit the mark. For us, it was a way to put the problem of workers’ power back on the agenda. In fact, we didn’t have to wait long for the response from the carabineri and the police, with searches inside the factories and provocations outside, dissolution of pickets and attempts to impede proletarian rounds. The trade union didn’t miss a chance to take part in these threats, in particular against the vanguards.

Our slogan of the day was, “Build organised workers’ power in the run up to collective bargaining”, clearly stated in our leaflets. In addition to the defence of jobs and wages, we focused on the question of prices in the territory: we engaged in so-called auto-reductions, we imposed price reductions for basic necessities and bills. There were not only people in the working class neighbourhoods involved in this, but also the factory workers. In this regard, I remember our interventions in the industrial zones of Padova, in front of Precisa, Monteverde, Unus, Ottogalli, Miazzo, Sordina, Antoniana: these were all factories controlled by the trade union and the PCI, but where the Collective North insisted on their intervention. The second slogan of the day was this one: “In the crisis we have to enforce our needs, more money, less work”. It was us who put these issues forward, not the trade union. For us, the struggle for political prices meant defending our wages. There were, for example, the interventions by the Collective North and the Gruppo Sociale di Pieve di Curtarolo, which got engaged in the mobilisation of proletarian housewives and workers in a few working class neighbourhoods in Padova in 1976, who practiced ‘shopping strikes’ in some local supermarkets – at Pam in Arvella, Despar in Brusegana, Dea in Guizza. We proposed the reconstruction of municipal shops, in particular in the villages, where basic necessities could be bought for reduced political prices.

Here we have to stress the independence of the Gruppo Sociale vis-a-vis our Collective North. The relationship between the two groups was not of the classic type of a transmission belt [between the political ‘the party’ and wider social organisations, where the party uses various social organisations as leverage or recruitment grounds – added by translator]. We were never a pyramid-type structure, a vertically organised ‘party’. In our case, the high and low levels of organisations could mix themselves up. During a particular argument, the social group might decide independently and drag the Collective with it; in a different situation the opposite might happen. We, as the Collective, certainly moved things forward, but always with the objective to defend this horizontality, against any form of verticalism. To put it briefly, the social groups were our soviets and that is how we understood them.

Regarding the municipal shops, we also have to remember the municipal pharmacies that were still present in our area, but they were slowly disappearing. In the crisis we tried to reanimate them. I remember well the battle around the imposition of local prices for bread. The natural outcome of this struggle was a series of police raids at houses of youngsters who were involved in the social groups. The cops searched for weapons, using all kinds of denunciations; and it was this theatre of repression and intimidation that would allow the trade union to propagate the idea inside the factories that we were dangerous, if not outright terrorists. But the usual trade union exercise was to sign sell-out contracts, like what happened during the dispute at Wierer in Curtarolo, a factory for building supplies. The demands were put forward by us and confirmed by the factory council [an official formal representative body – added by translator]: we demanded a wage increase, a fourteenth monthly wage due to the health risks at work, a canteen and a staff shop. When it came to the agreement, the union sold out. It was now clear that this was the line of conduct of the trade union within our factory confrontations: spit on us, if they could, or present our proposals as their own ones if they couldn’t, and then sell them out during the agreement.

In order to grasp the complexity of the intervention of the Collective North in Padova in 1976, you should at least read the third of the three bulletins published that year; the issues ranged from the collective bargaining in small and medium-sized factories, to the social groups and the strengthening of the regional workers’ coordination, to the question of political prices, to the RAF of Ulrike Meinhof, to an invitation to workers to put their name on the electoral ballot papers for the 1976 elections, those won by the PCI. It was actually about the use of workers’ power, of which we started to see hints of, thanks to the practice of the proletarian rounds. The rounds were an extension of the regional workers’ coordination and the social structures in the territory and villages. In particular the workers’ coordination, in addition to the structures in the metal sector, started to intervene in other sectors, for example the furniture and shoe factories of the industrial zone. I remember that there was no trade union presence in these sectors. The unions were absent to such a degree that the social group in Fiesso d’Artico published a pamphlet explaining the Statuto dei lavoratori [a legal text with the basic labour rights in Italy – added by translator]. It was on our shoulders to familiarise the workers with its existence, the workers were not aware of it. The appreciation and use of the Statuto was based on the fact that we were still in a transition period from one class composition to the other; according to our view, after 1977 and the loss of the centrality of the big factories, the Statuto lost its relevance.

Returning to our factory interventions through, in this case, the Gruppo sociale San Giorgio delle Pertiche, we have to remember companies like l’Aermatic, Ilva and the workshops San Giorgio; but here we also occupied ourselves with the process of decentralisation and working from home, for example at Pavan di Galliera Veneta. We always stressed that decentralisation was the small bosses’ slogan of the day because it guaranteed enormous profits. We had to deal with these small bosses who employed two or three workers, we had to explain that the boss is not an ally of the working class, that he is not their friend. This workers’ struggle was accompanied by an initiative about prices in the villages through public assemblies with the purpose to strengthen already existing organs like the Consigli di contrada (municipal assemblies), in order to link these up with the (official) factory councils and the workers in the industrial zone. There was a need to connect the villages with each other because they all had the same problems.

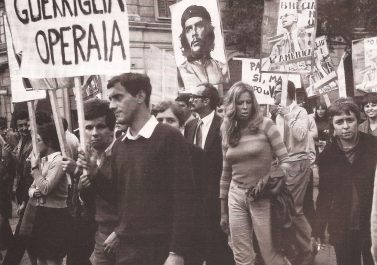

To continue with the narrative of 1976, at the end of May in Sezze Romano, during a demonstration against the fascist rally by Sandro Saccucci, an ex military and leading participant in a coup attempt, the fascists fired shots and killed a militant of the Federazione Giovanile Comunisti Italiani ( FGCI ), Luigi Di Rosa, and injured a militant from Lotta Continua; in response there was a demonstration by many organisations on the following day in Venice against a rally by the fascist MSI leader, Gestone Nencioni. The rally was banned, but the demonstration took place nevertheless, close to the local MSI office. The cops fired a few pistol shots, followed by tear gas. Our comrade Diego was seriously injured. Still, in hospital he was framed with the accusation of having provoked the police. Even today the comrade still carries the scars of this injury. At the end of June, another of our comrades was arrested in Padova and accused of having seriously injured two fascists, one of whom was a defendant in an ongoing court case in Padova against the so-called ‘thirty three black-shirts’; (…) But in terms of antifascism the events in Arcella were our little master stroke. I talk about our response to the threat of the fascist MSI leader Almirante returning to Padova. For this occasion we, as the political collectives, had invited the factory councils to mobilise workers to stop the fascist rally from happening, whereas the PCI only invited people for a so-called ‘democratic vigil’. Why the area of Archella? We were conscious of the fact that we had to rely only on our own strength and that the practice of some kind of urban guerilla was not practicable in a small city like ours. We therefore focused our response within an area that we knew well, precisely within Archella, where the headquarter of a historically significant branch of the MSI was located.The events of the day still are still really vivid to me. On the day before the Almirante rally, we blockaded the entry routes into the neighbourhood with a large group of comrades, which included the overpass to the train station; a separate group attacked the MSI headquarter in order to destroy it and they didn’t forget the pizzeria Sajonara, which was a meeting place for fascists. A third group moved to the house of Fachini, the fascist murderer [2], attacking it with bottles and some pistol shots. Comrades from Venice, Mestre and Vicenza had been invited to take part in these actions. A big success, also because Almirante cancelled his rally. We managed to sweep everyone off the streets: the fascists, the police and caribinieri, and the PCI, which had to keep a low profile. The chosen and achieved objectives of involving hundreds of comrades and the outcome of the action were clear proofs for our maturity and strength. There were no confrontations, no contact with the police, no one had been stopped or arrested. It was only the fascist headquarters that had been destroyed and only Fachini, the associate of the murderers Freda and Ventura, was threatened with weapons. This was a visible success, to the point that some comrades of the group ‘Classe e Partito’ from Vicenza and some former members of Lotta Continua from Thiene decided to join us and form the Political Collectives of Vicenza.

During late 1976 and early 1977, the Gruppo sociale del Piazzolese organised and practiced protest blockades in the periphery of Padova against the increases in ticket prices and travel cards on the rail-lines between Padova and Piazzola, amongst others. This was an attempt to create commuter committees on different rail-lines and zones in order to get working class areas and villages involved through demonstrations, road blockades and occupations of buildings of the municipal administration. This struggle joined other parallel initiatives in the province that had been pushed by commuter committees, with the slogan “We won’t pay for the rail card!”.

The workers’ coordination in the west of Padova intervened with the proletarian rounds against overtime, which was accepted as a way to increase workers’ income. Why don’t we wrestle more money from the bosses in order to avoid having to work longer hours? For us the defence and recuperation of the wage had to develop on two levels: 1) in monetary terms, with an increase in bonuses, a fourteenth monthly wage and control over the progression from one job category to the other; 2) in real terms, through the imposition of political prices of basic goods, rent, transport and staff shops. These two forms of wages formed for us the so-called political wage, comprising the wage from the factory that we receive in our pay cheque, and outside the factory, comprising the prices of pasta and bread, of transport and canteens. Therefore, in our battle against overtime, we also turned towards the factory councils and the so-called ‘leagues of the unemployed’, which was a more or less fictitious and short lived organisation pulled up by the PCI and the trade union. In order to be effective, we would need to organise the pickets not only when the bosses asked for occasional overtime. Rather, in a situation of high unemployment, each Saturday shift had to be combatted through proletarian rounds, and not only in the medium and large factories. The round was a form of struggle that would involve mainly the unemployed; they went in front of the factories, also with the workers of the factory, to blockade overtime shifts. For the unemployed, this was the only possible form of struggle through which they could regain their dignity, because it allowed them to fight for their interests.

Also in 1977, the Gruppo sociale Loreggia and the workers’ coordination in the north of Padova intervened in smaller manufacturing units, (…), mainly dealing with the textile and garment sector. We supported the struggle of workers at HOMME in particular, who managed to wrestle a minimum of regulation for their work from home. For the first time, the arrogance of the bosses was defeated. Based on this first victory we proposed to set up zonal assemblies to elect delegates amongst the textile workers who worked from home, who could then coordinate the struggle together with the factory workers. A way to overcome the existing divisions within the class. But this type of struggle didn’t aim at the abolition of work from home, because this was impossible to even imagine. Apart from women, this domestic sector employed the elderly and children, not to mention unemployed and dismissed workers. Women workers were forced to do these shit jobs, because, as far as they were housewives, they could not take a factory job due to the lack of nurseries for their children and public transport for their commute. It was therefore no coincidence that we started to agitate around these issues, besides the struggle to reign in the self-exploitation at home somehow. We proposed to confront the municipal administration on the terrain of public services and expenditures. The struggle of the women workers at Loreggia allows me to speak more about feminism, which was particularly strong in Padova thanks to several female comrades who were enrolled in the political science department at the university. Here I obviously speak about Alisa de Re and Mariarosa Dalla Costa [3], whose merit, I think, was to raise the problem of the conditions of exploitations that working class women were subjected to at home with having to prioritise domestic labour.

Footnotes:

[1] More on the political tendency of Operaismo (workersism):

The Renaissance of Operaismo – Wildcat – Angry Workers