Introduction from translating AngryWorkers

This article on the Italian Marxist current of the 1960s and ‘70s, which later on came to be known as ‘Operaismo’ (workerism), was originally published in German by comrades of the magazine Wildcat in 1995 – we now present you a re-worked translation. At the time, the Wildcat collective noticed a renewed interest in the works of Italian groups and comrades attached to Operaismo within the wider left. Referring to a talk by Sergio Bologna, they drew some parallels between the social situation that the early Operaisti grappled with in the late 1950s and the situation after 1989. In the late 1950s, the left was shocked by the invasion of Soviet tanks into Hungary and the discovery of Stalinist crimes, while in 1989 the left was shaken by the final collapse of state socialism. In the 1950s, the assembly line system expanded rapidly and the productive network became integrated into the European market, while in the early 1990s the ‘Japanese’ production system (team work, lean production, just-in-time) was transforming existing conditions in workplaces and the productive network became truly globalised. Both eras of social transformation undermined existing theoretical convictions within the left and required re-thinking.

Over a quarter of a century later, we can say with a certain confidence that we are witnessing another ‘renaissance’, another re-birth of Operaismo. There is a more widespread interest in the concept of ‘workers inquiry’, there are various efforts to translate early writings, first of all by prominent figures such as Tronti. Similar to the moments in the 1950s and 1990s, this interest will have much to do with a productive political uncertainty: the end of US hegemony, the further penetration of IT technologies into workplaces, the financial and ideological decline of ‘neoliberalism’ on one hand and the apparent weaknesses of 21st century socialism (Chavez, Lula, Syriza, Podemos etc.) on the other. Unlike the 1990s, (thankfully!), ‘work’ is not excluded from the political discourse anymore. After the neoliberal house of cards has been shaken, so too has the illusion that ‘development’ is detached from concrete labour. Everyone who wants social change is forced again to talk about ‘work’. The problem is that while people talk about work, workers are primarily dealt with as victims or pawns.

Though we welcome the current efforts to re-engage with Operaismo, we can also see some significant weaknesses in the way this is done. Due to the largely academic confinement of the current debate, we can see that the legacy of Operaismo as an effort to develop revolutionary working class strategy becomes contained and sterilised. This happens by detaching the element of ‘workers inquiry’ or ‘class composition’ from the question of political organisation. It seems as if the largely academic comrades feel that they have to provide trade unions and workers’ militants with ‘new tools of organising’, and they offer workers’ inquiry or the concept of class composition as such tools. Workers’ inquiry is thereby reduced to a more elaborate method of ‘workplace mapping’, looking for the weak spots of particular companies and possible ‘choke-points’ beyond the company boundaries. While these are useful things to do when trying to organise a concrete struggle, workers’ inquiry in its original conception was always an effort to show the political limitations of singular disputes and the necessity of wider political critique and organisation!

By detaching workers’ inquiry from the question of political strategy, the question of ‘organisation’ remains isolated and can thereby be re-integrated into pretty conventional political avenues. The translation of Tronti or the works of Negri can then be used to argue for an ‘in and against’ strategy, which promotes working within the parliamentary circus of Labour or DSA, while, of course, also building ‘the movement’. In this conception of organisation, workers’ struggles are reduced to a mechanical force, transferred primarily through the trade unions, that is supposed to support a ‘socialist’ government and to hold it to account. Once again, the economic and political struggle is separated.

It is therefore not surprising that the re-emerged interest in Operaismo is selective. We see interest in singular inquiries and broader philosophy, but not so much in the concrete experiences of political working class organisation in the 1970s, such as the political workers’ committees. In many articles, Operaismo is reduced to its’ early efforts within the traditional political parties and trade unions or to the hype of outstanding figures, such as Negri and the insurrectionist wing of workers’ autonomy. With the publishing of this re-worked translation we, as AngryWorkers, want to encourage a debate about the relation between day-to-day struggle and the wider political strategy of working class autonomy. We will engage in a series of readings and discussions of Operaismo articles in the near future – feel welcome to join in!

———

Operaismo and Workers Inquiry

In 1989 Sergio Bologna started a lecture about Gramsci’s ‘Americanismo e Fordismo’ with a description of the situation of the left in Italy. He began by recalling the years 1969-73, where, in Italy, as in no other country in the world, the “factory as the site of working class self-organisation and the development of new modes of behaviour, as a laboratory of a new subjectivity” exercised a “hegemony” over the whole society and the party system.

In contrast to this, ‘work’ today has been politically excluded in a grotesque way, the working class characterised as environmentally unfriendly and uncooperative, as a hindrance to social and technical innovation. “No-one speaks of ‘workers’ as a collective anymore, one always speaks of individual groups”. Bologna evaluates this as a “cultural crisis”.

On one hand, racism is becoming noticeable in large sections of the population. On the other hand, a new anti-racism is emerging: “While the left is suppressing its traditional base, it is at the same time utterly possessed by philanthropic activism concerning the new immigrants. The indigenous sections of the proletariat feel even more excluded by this, resulting in festering anti-migrant sentiments […] The new ‘friends of the environment’ and a section of the Greens have succeeded in making a big contribution to the cultural-political exclusion of the working class with their idea of the working class as a hindrance to environmentally-friendly innovations”. They wilfully ignore the fact that in the 1970s the workers themselves formed a movement against the unhealthy and destructive effects of the factories.

Bitter words of a “mouldy” Operaist [1] about the left in Italy. A left who have thrown away their past and their instruments of analysis with one mighty heave and whose cult of consciousness lets the middle class’s hate towards workers shine through. [2]

Five years later, in November ’94, at a small conference organised by the newspapers ‘Collegamenti-Wobbly’ and ‘Per il ’69’, a new development became apparent: a recollection of the concept and praxis of ‘workers inquiry’ and the resumption of a discussion that had been violently broken off by the repression from 1979 onwards. In time for this conference, new publications were released, which presented these historical initiatives of workers’ inquiry with all their contradictions and experimental character – avoiding the usual reductionism of organisations who have an interest in presenting themselves in a good light, rather than in critical reflection. At the conference, comrades who had been active at the end of the ’50s reported their ‘workers inquiry’ initiatives in the textile factories, automobile and electro-mechanical industries to the ‘youth’. One contribution to the discussion compared the social situation comrades faced in the beginning of the ’60s with the situation today and remarked on a few similarities:

- “Socialism” has died twice: in Budapest in 1956 and with the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989.

- In the early ’60s there was a qualitative leap in the development of the European market; today this kind of leap is taking place in the world market.

- The violent restructuring in the factories during the transition phase to mass production back then, and to “lean production” today.

- A qualitative leap in terms of migration (in the ’60s the movement of millions of proletarians from the south to the north of Italy; today the migration from Eastern Europe and North Africa).

- As well as this, the crisis that the unions find themselves stuck in today is similar to the early ’60s.

For a small group of socialists and communists, whose world view had been shaken and for whom the ideologies that had been handed down were not sufficient explanations, the above mentioned social transformations of the late ’50s acted as an impetus for a fundamental process of inquiry.

But history does not repeat itself! Every cycle of economic expansion brings with it an increase in potential workers’ power, but this does not necessarily amount to the emergence of new struggles. The situation today cries out for a radical effort of political reorientation, similar to the one that the militants of the workers’ inquiry undertook in the late ‘50s and early ’60s. It is only through such an effort that we can get to grips with the real conditions of exploitation and its existence as a constant conflict and discover the potential for change.

What is militant inquiry?

Inquiry is something concrete that all revolutionaries should engage in, and most of them have done. In contrast to bourgeois ideology and the corset of orthodox Marxism, it is to look at the real social and material relations, just as Marx himself did. In doing so we have to treat Marxist ideology in the same way as Marx dealt with bourgeois science.

To engage in inquiry is to break with the official myths, to be engaged with real people, to ask them questions without knowing beforehand what is supposed to come out of it. On the other hand, it also means political-theoretical work. In order to know what questions to ask, a hypothesis is necessary. Hypotheses about how the class will establish itself anew as a political subject in the process of radical change.

As a basis for such an inquiry today we suggest the text by Karl Heinz Roth [3], in which he puts forward the hypotheses that a new proletariat is developing, and developing on a worldwide scale. In the six months after its appearance the text was, rightly, knocked down for its theoretical and analytical weaknesses in many discussion circles. Now the work of a collective inquiry has to begin, that attempts to find out what this ‘re-making’ of the proletariat really looks like. Otherwise the discussion will remain an academic hobby.

An inquiry would, firstly, examine the hypotheses through large-scale discussions with workers in modern factories, ‘precarious’ or ‘casual’ workers, immigrants, so-called self-employed workers etc. Secondly, in the process of these discussions an inquiry would have to develop more exact concepts, as, for example, ‘multitude’ or ‘precariat’ are rather superficial ones. Thirdly, inquiry means to actively intervene with initiatives of struggle and attempts at organising, in order to accelerate the collective process of understanding and to uncover the underlying tendency to communism that resonates in the class movements. To work together with the workers, to find forms of struggle that are not repetitions of the old ones.

The beginnings of workers’ inquiry in Italy

In the following, we want to present the first of the above points (the method) and also the third (the intervention), using the workers’ inquiries in Italy in the early ’60s as an example. To do this we have to start by sweeping out of the way a few myths about those genius Italian Operaists. Workers’ Inquiry is neither an Italian invention, nor only feasible in Italy. Neither is it a crowbar that can create struggles where there aren’t any, nor find the ‘Archimedes point’ to lever the system off its hinges (as it was described at the time!). But through their inquiry the Operaists were prepared for the coming struggles, had analysed the problems within the factories and had followed the workers discussions, in order to be able to write down and circulate workers’ demands in leaflets and assert them as a political line in meetings and assemblies. They had learned, “that there is already struggle, before it breaks out into the open”. [4]

One difficulty in the reconstruction of the workers’ struggles in the early ’60s and the beginnings of ‘Operaist’ theory lies in the fact that the history started to be written retrospectively, starting from the end of this phase, i.e. the experience of the ‘Hot Autumn’ of 1969. As a result, the beginnings of this movement have been simplified in hindsight, as for example Dario Lanzardo showed in the subsequent reflection of the events that took place in the Piazza Statuto in Turin in 1962. He criticised the subsequent written history that gives the impression that “the mass worker” marched as a compact block out of the factories and into the town centre and revolted against the unions. In the Fiat plant, from where the workers’ demo started, there were no immigrants from the South employed, but rather almost all were skilled workers from the Piedmont region of Italy. 600 workers took part in the demo. At the riot at the end it was mostly young people and the residents of the surrounding proletarian parts of the town who took part in large numbers. As to who they really were, there were only strongly politically biased opinions. From the legal case notes you can see that quite a few young PCI (Communist Party of Italy) members took part, who later found themselves in trouble with the party because of this. [5]

During the ’50s, Italy went through an epochal transformation. The development of industry and the booming economy attracted millions of people, who migrated from the poor south to the cities in the north and were not well received by the people living there, workers included. They were said to be stupid, uncivilised, apolitical, idiots who put up with anything, and who put downward pressure on wages. It was common at the time for landlords to hang up signs, “Room free. Not for Southern Italians”. The unprecedented rise of mass consumption was based on hard work, low wages and an iron command in the factories. At Fiat the active communist cadres were banned from the shop-floor or put out of action in out-of-the-way departments. The union had already given up on organising in Fiat factories and concentrated their work on smaller companies. On a political level the party of the working class took part in the ‘national reconstruction’ project and guaranteed social peace in exchange for workplaces.

At the end of the ’50s the situation for the Italian Left was characterised by the following facts: The soviet ‘mother-party’ had been shooting workers in uprisings in Berlin in 1953 and in Budapest in 1956, so their credibility was badly shaken in Western Europe. The socialist party (PSI), in which many anti-Stalinists had sought refuge, was on its way to social democracy. A process that ended in their taking part in government in 1963 and the division of the party. In 1959 workers of the textile industry in the region around Biella started the first self-organised strikes. In a few metal and chemical factories in the Po Valley, workers’ strikes broke out of the years of stagnation.

The new mixed economy in Italy, whose development was funded by Marshall Plan money after the Second World War, was termed ‘neo-capitalism’. The institutional left interpreted this development as a chance for a peaceful path towards socialism, through the expansion and control of the state sectors (an an anti-monopoly alliance). The left communists, on the other hand, saw it as the end of the working class’ revolutionary power, because the working class was being integrated into the system. Neo-capitalism meant planned capitalism. The dominant ideology was that everything can be planned and society thereby re-organised, e.g. by influencing behaviour through, amongst other things, the supply of consumer goods.

In the ’50s sociology was the corresponding dominant social science. (In the ’70s, when the emphasis was on the change of the individual person, psychology became the leading science, whereas today it is macro-economics, given the fact that the economy is once more seen as the dominant determining force). At the time, the mainstream of US industrial sociology announced the disappearance of the working class, the social integration of the ‘affluent worker’, their ‘assimilation into the middle classes’, and production becoming part of the so called ‘service sector’ (tertiarisation). In parallel, a ‘critical’ or left sociology developed, which started researching the work conditions in factories and miserable jobs, demanding the ‘humanisation’ of the organisation of work. ‘Participation’ and the discovery of the ‘whole person’ were the key words of the enlightened faction of capital. Olivetti, regarded as a ‘socially minded’ employer, brought psychologists and sociologists into the factory to improve ‘human relations’. The influential ‘party of the sociologists’ made politics, writes Alquati. [6]

Industrial sociologists’ main object of inquiry was the ‘new worker’, the ‘new working class’: the educated, skilled, technical worker, employed in highly technical or automated parts of production, who is clearly different from the image of the traditional working class. Sociologists predicted at the time that this figure would soon play a central role in the production process and that the form of conflicts within companies and industries would also change. An enormous amount of studies appeared on this subject, originating primarily from the USA and France, which were translated into Italian in the early ‘60s. They were published by, amongst other people, Montaldi and Panzieri in the left publishing houses Feltrinelli and Einaudi.

The socialist (non-Marxist) left fostered engagement with the new science, while Togliatti’s PCI were vehemently opposed to any kind of sociology, as were the traditional left-communist groups. Related to this was the fact that the PCI had not played any kind of role on the shop-floor or in industrial disputes for years and hardly discussed the changing relations in the new factories at all. The sociologists were the only ones who went into the factories and engaged with the changes in the organisation of work and the new modes of behaviour – a situation that is comparable today. While the remnants of the left retreat into ideology and repeat, parrot fashion, the latest ideas about ‘the end of mass production’ or ‘the chances of teamwork and job enrichment’, the multi-functional skilled worker experiences a steep increase in exploitation and work stress. Today, once more, workers are on their own.

The real working class did not have much to do with the ‘ideal working class’, who the institutions of the official labour movement claimed to represent. So some young political dissidents were eager to grasp the instruments of ‘field research’, which had been developed by sociologists in order to analyse the new reality of work. “It was mainly about the various facets of an initial exploration of the terrain. A terrain which both us and the official labour movement were ‘external’ to, and which was not easy to enter. Needless to say, it was also unknown to the wider left in Italy, and as long as one remains on the outside, the (French, English and American) industrial sociologists had some ideas to offer”. [7] To engage in an inquiry was a refusal of the orthodox Marxist habit of extrapolating the development of the working class from an analysis of capitalist development.

What is class, what is the working class? – The precursor of workers inquiry in France…

The anti-Stalinist left in France has a long tradition of inquiry. Already during the time of the popular front they discussed the epochal changes in working class composition through the introduction of semi-automatic machine tools. At the time, generally-trained skilled workers were being replaced by workers who had only been trained in the operation of particular machines. The Trotskyist militant and industrial sociologist Pierre Naville researched the antagonism in these new relations of production instead of ‘deriving’ the development of the working class from the technical development. He analysed, for example, the fact that working hours didn’t decline, but rather rose steeply with the introduction of new machinery. The reduction of the working day is purely the result of the struggle of the ‘workers’ coalition’. This discussion was published in his journal Cahiers Rouges [The Red Notebook].

The group Socialisme ou Barbarie [Socialism or Barbarism] originated from the tradition of council communism, and counted Lefort, Castoriadis and Mothe as some of its members. In the early ’50s they anticipated much of what would later become known as ‘workers’ autonomy’ in Italy. Following Marx’s theses (“the largest force of production is the revolutionary class itself”), Lefort [8] understood the proletariat not as a physical mass, as it was seen in orthodox Marxism, but rather as a self-forming subject of history. To work for the emancipation of the workers, means grasping the seeds of subjective self-constitution as the oppositional force against exploitation within the ‘proletarian experience’. You don’t work for their emancipation by giving sermons to the workers nor by proposing, once more, ‘the party’ as the ultimate solution and Deus ex machina to overcome the current status quo.

Lefort proposed an inquiry to understand the existing forms of cooperation within the social production process, which already point towards the overcoming of the capitalist mode of production. His main interest was in the specific character of the ‘proletarian experience’, from which the class would constitute itself. He wrote that the words from the Communist Manifesto have lost none of their explosive character: “The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles”. The pseudo-Marxists turned the theory of class struggle into an economic science and reduced the proletariat to performers of their economic function. Throughout history, though, the proletariat not only reacted, but rather acted and intervened, not according to some scheme predetermined by objective conditions, but on the basis of their own universal experience. It would be absurd to interpret the workers movement without continually reflecting on the economic structure of the society – but to reduce it to this structure means leaving out three quarters of concrete class behaviour.

The bourgeoisie, just like the working class, are united in their common interests. However, the common interest of the workers is something quite different: it lies in ceasing to be a worker. It means to radically negate, rather than to perform their economic function. The workers’ conditions of existence themselves demand a constant struggle for change, i.e. a constant questioning of their immediate fate. The advance in this struggle and the development of an ideological content that allows this questioning, form the experience through which the class will constitute itself.

Lefort tried to apply Marx’s hypothesis in the ‘German Ideology’ to the situation of the time: How do people appropriate their labour under the conditions of industrial work? How do they practically produce their relation to the rest of the society? How do they piece together a common experience, one that forms them into a historical power? He distances himself from Lenin’s view, in which the proletariat form one unity, whose historical task is set for all time, who are created by the relations of power and where only the relations of power are of interest. Lefort saw the activities of the proletariat in all their contradictions: on one hand in the form of resistance, which constantly forces the employer to improve the method of exploitation and, on the other, in their adjustments and active collaboration with the (technical) progress. Workers themselves find answers to the thousands of problems that are thrown up by the production process every day. The result of these daily adjustments and improvisations is then presented as a systematic answer and given the name ‘invention’. The process of ‘rationalisation’ or ‘optimisation’ of the production process thereby merely incorporates, interprets and integrates workers’ dispersed and anonymous innovations.

Up to this point, the proletariat had been researched in three ways: economically, ideologically and historically. Lefort suggested a fourth way or method: he wanted to reconstruct the proletariat’s attitude to work and to society from what was already happening within the proletariat itself. He wanted to demonstrate their inventiveness and their strong social organisation in daily life. Lefort was the first person to undertake an inquiry on this basis. It had not been done before – either by Marx or by the so-called ‘worker’ sociologists of the USA, who Lefort saw as doing the work of the bosses. The ‘enlightened’ capitalists had discovered that the process of technical or organisational rationalisation (such as automation or the reorganisation of work-steps) has its limits; that the human-object will react in a particular way; that one has to pay attention to them if one wants to exploit them effectively. But due to their class perspective, these sociologists can’t grasp or relate to the proletarian character, because they are approaching from the outside and are only able to see the worker as producer, as a mere performer, irrevocably bound up in the capitalist system of exploitation.

The inquiry of the social life of the proletariat should not be a study of the class from the outside – but should rather answer the precise questions that are being posed explicitly by the workers’ vanguard and implicitly by the majority of the class today. Lefort collected statements and accounts written by workers, life histories, individual experiences of the relations to their work, the relations to other workers, the social life outside of the factory and the bonds of a proletarian tradition and history. He writes that opinions can change, that they often carry with them mystifications but that, “all workers have got in common the experience of exploitation, the experience of alienation – all workers know this. Every bourgeois person notices this straightaway when they enter a working class area”. To discover this workers’ mode of behaviour is the aim of the inquiry. Is there a ‘class mentality’?

By adopting this perspective Lefort is by no means aiming at a ‘workerism’ that denies the necessity of a critical theory. The opposite is true, as he has always distanced himself from this type of ‘workerism’: “From a revolutionary standpoint, the act of gathering this kind of information could enable us to show how a worker fuses with their class and whether their relationship with their social group is different from a petit-bourgeois’ or bourgeois’ relationship with his or her own group. Does the proletarian connect their fate, on all levels of his existence, consciously or not, with the fate of their class? Are we able to verify the classic, and often too abstract, concepts such as ‘class consciousness’ and ‘class behaviour’ in concrete terms? According to Marx, the proletarian, in contrast to the bourgeois, is not simply a member of their class, they are an individual member of a community, and they are conscious of the fact that they can only liberate themselves collectively. Can we concretely verify this assumption?”

… and in Italy: Danilo Montaldi

The communist Danilo Montaldi, who had been expelled from the PCI, built up a small group around him in Cremona and wrote for various left communist newspapers. He learned about the theory and practice of workers inquiry from his contact with Socialisme ou Barbarie. He translated a few workers’ biographies into Italian and took part in similar projects. In 1960 he published an inquiry into the life of immigrants from south Italy living in Milan with the title ‘Milan, Korea’. Montaldi didn’t use any consistent ‘method’: he worked in an ‘interdisciplinary’ way, using literary elements, for instance letting people write out their stories and histories using their own means of expression. And he used methods from sociology, a subject he had looked at in detail. Montaldi’s works are a constant search of the subjective as a means of understanding the history and life of the class. Whether it was the inquiry on immigrants from the south, on the life of the sub-proletariat during Fascism or on the experiences of political rank and file militants, he was always searching for communism as a ‘structural need’, searching for the subjectivity of the class, the ‘class for itself’. All this formed part of his effort to reconstruct a ‘class party’, a party consisting of ‘comrades who can have membership cards of various different parties’.

Montaldi researched the reality around him. His work was explicitly directed against the mysteries of the ‘true primitive man’ that was used at the end of the ’50s to suppress thoughts about the present. The type of academic work he criticised is surprisingly reminiscent of the way oral history has been practiced here in the last 20 years (i.e. often lacking context, celebrating ‘marginal life forms’, having given up on class struggle).

”While the industry in Italy becomes more concentrated, while the agricultural world goes from one crisis to another […] this great mourning for the past way of life or for remaining antiquated ways of life increases. The enthusiasm, research and analysis of what is not current, what is marginal. In this persistent hunt lies something retrograde, a false consciousness of the society in which we live, a shrinking back. While in the last few years, the dictatorship of the monopoly in Italy has become ever more public, the cultural interest focuses on those aspects of social life that are in the process of declining. This is not so bad, if it is about bringing to light the totality of the everyday conditions from the south up to the north. But within the analysis that attempts to interpret the antiquated lifestyle, there is almost always a glaring omission of the fact that this phenomenon is connected with the present system. This tendency encourages a certain cultural reformism that is itself an expression of a crisis. A reformism that expresses the wish to be a part of the antiquated forms of life itself […] But we can see the effects that it has on a cultural level. […] chronicles of the manners and customs of the descendants of the Ligurians, who settled in Sardinia 400 years ago, are more ‘interesting’ than the situation in the Fiat production plants; the dialect of our remote and distant ancestors is surely more beautiful than the non-accidental silence of the workers in the rank-and-file organisations. We are not interested in the folkloristic aspects of this type of social research, but rather in looking at how this figure of an ahistorical person has been set up between and amongst us. One who has fate and nature as his enemies”. [9]

The Quaderni Rossi

Italian Operaismo originated in discussion circles around the journal Quaderni Rossi, which first appeared in Turin in 1961. (Quaderni Rossi also means ‘red notebook’ and so shows their connection to Cahiers Rouges). The comrades who gathered around the paper were mainly young comrades from the PSI (Socialist Party of Italy) and PCI, some of whom had left their parties, and some of whom were still members. They were joined by union activists and students, those who were searching for new ways of doing practical political work and theoretical debate. We have to note that, for the majority of them, ‘Operaismo’ was a derogatory term from which they strongly distanced themselves, just as much as from the insult of ‘anarcho-syndicalism’. They saw themselves not as extremists, but as representatives of a majority current of the working class. ‘Operaismo’, as a political culture, only became acceptable once the actual workers’ struggles after 1969 turned the political situation in Italy on its head for several years.

The Quaderni Rossi journal was a catalyst and point of convergence of various political ‘scenes’, interests and political approaches that saw themselves as an internal and external opposition to the institutional labour movement. They critically examined the theories that were being discussed around the globe, related to and absorbed anti-Stalinist experiences and re-read Marx. Their emphasis was clearly on the inquiry into the class antagonism within the production process. Raniero Panzieri is seen as the ‘founder’ of the project and a man full of ideas and inspiration. He was an intellectual from Rome who, as a PSI official, had helped organise land workers’ struggles in Sicily in the ’50s. He had also made a new Italian translation of the second volume of Capital. His initial aim was to put the Socialist Party back on a ‘revolutionary’ course i.e. to fight against its increasingly social democratic direction and its aim of taking part in government. Rather than being based on its participation in parliament, Panzieri wanted to deepen the party’s base amongst land and factory workers. He, as chief editor, used the party newspaper ‘Mondo Operaio’ [Workers’ World] as an instrument. He initiated a broad discussion with his text ‘Theses on Workers’ Control’, written together with Libertini, which was a strong critique of the concept of state socialism. When he failed to impose his political course inside the party, he moved to Turin “to find the working class inside the factory again”. In 1961, after years of conflict, he finally left the PSI central committee.

The times were over where everything happened inside the official organisations. In 1960 Panzieri had a discussion with the socialist leader Lelio Basso on the question,”should one be active in the historical party of the labour movement or in political groups that intervene autonomously?” Panzieri took the standpoint, that when facing a situation where not only a section of the party, but the party itself (the PSI), was in a crisis, one “should not put new wine into old flasks”, but rather search for a political line “on the level of the rank-and-file itself”; instead of clinging onto a political inheritance that has become redundant, the starting-point should be, “a process of examination and verification that the movement today fortunately allows us to engage in”. [10] After a discussion in the PSI office in Mestre, attended by a large number of workers, he wrote to Montaldi:

“It would really be a shame, if we would allow that such a lively force be confined to the current narrow corridors, bottlenecks and mystifications of the PSI (and the same goes for the PCI). I am more and more convinced that we have to create focus points totally independent from the party structure and hierarchy, which these class forces can refer to with full trust. These are forces that are conscious of the lies of the official politics of the parties, but do not want to renounce the need for an association. An association which doesn’t become the vehicle of their trust in the ‘authorities’, but of their consciousness and their class solidarity, and thereby becomes a concrete force against the bosses, a revolutionary will. We have to tackle the practical problem; how we can create a connection between the various groups with a revolutionary orientation, both within and outside of the parties, in an organisationally open form – in so far as one has to avoid any appearance of being a small sect, as that is the most terrible error which all small groups of the workers’ left commit”. [11]

Panzieri saw the Quaderni Rossi journal as a political instrument directed at creating a unified / unifying revolutionary movement of the working class, i.e. one not divided into the various parties. The group drew hope for a revival in the workers’ movement from the 1959 strike wave in the metal and textile industries and above all from the actions against the Party Day of the MSI [Social Movement of Italy, the fascist party] in 1960 in Genoa, the main town of communist resistance. For the first time, lots of young workers took part in the militant demonstrations. In the emergence of these ‘new forces’, a generation that was no longer characterised by the Resistance, Quaderni Rossi identified a possible reversal of the situation at Fiat, the ‘middle point’ of capitalist development in Italy. [12]

“We took part in the metal workers strike on Christmas Eve, 1959. A small group of comrades in Milan had begun to research the situation at Marelli, Pirelli etc. On the whole, between 1958 and 1961 we began the analysis and engagement with the factories like unravelling a puzzle, and to recreate contacts with the workers inside these factories… So the revolt of the workers against the fascists in Genoa in July 1960 was extremely meaningful for us. In this movement that kicked off against the Tambroni government across the whole of Italy, there was clearly a potential of rupture on a mass scale. This really whipped up the comrades and inspired them to drive forward the inquiry and organising. In my opinion 1960 was exceptionally important for several comrades and for myself. It was the first time that we found ourselves with precise functions inside a mass movement. We noticed for the first time its extraordinary strength and its capability to turn the power relations upside-down, through workers’ militancy and proletarian mode of behaviour”. [13]

The inquiry was the means of approaching the ‘real working class’. In Italy at the time there were a few small groups undertaking such ‘inquiries’ and discussing the political consequences. Usually ‘inquiries’ of the time came from ‘outside’, although leaflets and workers’ newspapers were written and produced together with workers who took part in group meetings. There is only little written material remaining from a few of these inquiries. Some of the familiar ones about the conditions at Fiat or Olivetti were more or less individual achievements. Individual achievements that nevertheless allowed particular hypotheses to be put forward that then became the basis for political work. From the interviews with young union activists at Fiat emerged a new picture of the working class, whose aspirations and desires Alquati summarised in a new ‘figure’: the young technical workers who enjoyed skilled workers’ training at technical college, who were dissatisfied with the work at Fiat, who confidently believed that they could manage production themselves – and in reality had to undertake ‘stupid and stupefying work’. In this widening gap between new aspirations, “the confidence to be able to run production”, qualifications and the actual work reality, Alquati saw an explosive contradiction that led to the destruction of the myth of neo-capitalism.

The practice of inquiry

‘Biographical approach’, ‘intensive interviews’… today everyone from feminists to left sociologists practices these inquiry methods. The difference of the ‘workers’ inquiry’ is that they started from a collective dimension: the self-constitution of the class, the detection of communism in the movement of the working class itself. “Porto Marghera [location of the petrochemical industry on the mainland across from Venice] was the laboratory in which we verified the situation with scientific methods. One could not begin to have a political discourse without what we called ‘workers’ inquiry’. We were determined to clarify once again what the workers standpoint was in concrete, because they were the social figures that were strategically relevant in the process towards the ‘new’. [14]

There was a serious political confrontation within the group around the fundamental question of whether the instrument of sociology could be applied critically. This went from the tendency that reduced Marxism to a mere sociology on one side, to the critical application of sociological instruments on another. Others went further and aimed at the abolition [Aufhebung] of the difference between inquirer and the objects of the inquiry, the workers, promoting ‘workers’ self-inquiry’. The latter two positions called their practice ‘Conricerca’, word-for-word meaning; ‘with-inquiry’. Liliana Lanzardo explained in November 1994 in Turin, that today it is much clearer to see the difference between those who wanted to do an academic inquiry and those for whom it was about a political project; at the time there was no terminology at all. Today, a few of their fellow militants of the time are recognised industrial sociologists – in the worst sense. [15]

By 1975 Alquati had already demystified the heroic chorus about the initial practice of inquiry. He wrote that ‘workers’ inquiry’ as a slogan was supposed to be a provocation, because the institutional labour movement was just as ‘anti-worker’ as its left workerist component. “When we said ‘class inquiry’ in the early 1960, for us it had the same meaning as ‘revolution’ or ‘revolutionary process’.” In reality comrades engaged not in a ‘workers’ inquiry’, in the sense of a workers’ self-inquiry, but in a sociological inquiry about the working class. The individual workers who took part were the source of information and knowledge that the group then processed further outside the factory, in order to prepare the second phase of ‘intervention’. According to Alquati, they never actually managed this transition to the second phase, which would have presupposed a relation to collective workers and put the emphasis on the subjective movement, because ‘the collective worker’ cannot be equated with ‘a group of workers’, but rather refers to the political organisation of the workers. This organisation did not exist, but only its precursor, workers’ autonomy. This is why one part of the group had ‘provisionally’ started by engaging in sociological inquiry, whereas the other part focused on the reconstitution of an actual political organisation of the working class as the means to realise the sociological inquiry. [16]

The sociology students within the group did the first inquiries. The rest of the group were worried about the difficulties and did not consider themselves prepared enough. In concrete terms the work of inquiry meant working through material about the restructuring of industries, analysing the various work tasks and steps within the work process, researching the machinery and the factory system with its, possibly explosive, contradictions. There were only a few, but very intensive, interviews – “everything was new and interesting”, Liliana Lanzardo described her enthusiasm of the time. But none of it was Conricerca, the process was known only to the interviewers, there was no parity between the inquirer and the inquired. However, this parity was easier to achieve in small companies, where workers’ newspapers were produced together with workers. The contact with workers was established primarily through the metal workers unions FIM and FIOM, who in Turin were very open towards the project, at least initially. [17]

The mainstream sociological research of particular industries discovers conflicts everywhere. But usually the bourgeois sociologists examine these conflicts as problems that are there to be solved in order to guarantee the smooth functioning of the factory. And the ‘critical’ sociologists expose the conflicts to prove that the factory does not function perfectly. In contrast to this, the comrades, schooled on Marx, took the contradiction of the work process as the starting point of the inquiry. Thereby they could understand how micro-conflicts could also be functional for the valorisation process, and which functions of the hierarchy within companies – from representatives to quality controllers to management – are there to prevent these conflicts from turning into a united struggle.

“The socialist use of sociology requires a rethink. It requires studying these instruments in the light of the main hypotheses that one puts forward, and that can be summarised as follows: conflicts can turn into antagonisms and thereby cease to be functional for the system. We have to take into account that the conflicts are functional for the system, because it is a system that further develops itself out of these conflicts”. However, the relation between conflict and antagonism is best researched in a situation of struggle, what Panzieri calls ‘hot inquiry’, “because workers hold certain values in normal times that they don’t hold anymore in times of class conflict, and vice versa”. The relationship between workers’ solidarity and a rejection of the capitalist system should be researched: “… to what extent are workers, faced with an unequal capitalist society, consciously demanding an egalitarian society, and to what extent are they aware that this could become a common social value”. [18] However, reading this text, it also becomes clear that in a few essential points, Panzieri wasn’t able to overcome his former role as a party cadre. He writes about the possibility of identifying and “raising” the consciousness of the workers.

The antagonism within the production process

In the introduction to the Italian edition of the diary of the Renault worker Daniel Mothé (‘Militant chez Renault’), Panzieri elaborates on the antagonism within the relation of production. “The book […] goes beyond the usual testimonies of the worker’s conditions, testimonies that mostly merely express sympathy with the situation of the factory worker (and no more than this). In Mothé’s diary the problems of the working class in a large modern factory, in all their complexities and specific reality, are shown step by step through the keen and thoughtful observations of the everyday life in one department. Initially, the book deals with the so-called ‘rational organisation of work’, such as time-and-motion studies etc.. There is a contradiction between, on the one hand, the attempt at a rational organisation of work that isolates the individual workers more and more; and, on the other hand, the conditions within which the work has to develop and be improved, as this development requires the constant breaking of official rules. Only through daily transgressions and improvisations can production run smoothly and make sense, e.g. in the form of the quality of the product. The worker has to fight against the implementation of these ‘rationalisations’, as they have to exclude any qualified human experience in order to be put into practice. They have to exclude experiences such as the legitimate need to connect to other colleagues – a need within which appears the value of an unshakeable solidarity – and the experience of cooperative work itself which brings the worker to understand his own problems as collective ones”. [19] The Olivetti text by Alquati is a good example of how the Italian Operaists used these preliminary works by Mothe and others in a fruitful manner. In the following, we want to show how he applied Mothe’s insight that, “the rules have to be constantly broken so that the production can run” to the inquiry at Olivetti. [20]

The workers, who at first took for granted all the official myths about the ‘rational’ organisation of work at Olivetti, which at the time was seen as a very ‘modern’ company, finally came to the following verdict: “Everything here is organised and determined, down to the smallest things, but despite this, there are many important things about the work that don’t function. If one sees that despite the meticulous organisation things don’t work like they should, one could almost come to the conclusion that organised disorganisation is being studied at Olivetti”. [21] Alquati goes on to extract the negative side of this ‘workers’ critique’ and formulates the hypothesis that the individual worker is unable to see the fundamental collective contradiction within the everyday small contradictions – precisely because it is “in these micro-conflicts” where the “fundamental contradictions of the system become as one, are developed and reproduced”. [22]

The fundamental contradiction is that in capitalism the work process (the production of use value) and the valorisation process (the production of exchange value) are both intrinsic, but contradictory elements of the same production process – and the worker is at the heart of this process. The capitalist is interested in the profit, which is based on the commodity containing surplus value, i.e. the valorisation process. But only goods can be sold that also have a use value, that have been turned into useful things through the work process. In the production process as a contradictory unity of work and the valorisation process, the worker is on one hand trained to make sure that the quality of the product is preserved (so that the goods remain saleable), on the other hand she is supposed to produce as fast and as many products as possible, in order to increase the surplus value.

“The worker, locked into her use value sphere,” can’t develop an understanding of this contradiction because her critique remains individual and starts from the point that one could produce the products more rationally, with fewer hand movements, with better quality etc. Moreover the capitalist organisation of work actually ensures that the individual worker perfects the exploitation through her ‘critique’. She has to constantly strive to create breathing spaces, in order to make the work at all bearable; breathing spaces that the time keeper takes away bit by bit, the result being that her ways and means of creating these breathing spaces eventually confront her as ‘invention’ or corporate measures of productive improvement. In the factory, “the worker, in order to survive, develops the mechanism that is squeezing her, which she has the freedom to do in cooperation with other workers”. [23] This includes the workers, in their cooperation with each other, constantly breaking the official rules and constantly re-arranging the division of work amongst themselves. (This process, analysed by Alquati as a process of ‘accumulation of tasks’, offers a good starting point, e.g. to analyse the modern concept of teamwork).

In his discussion with the workers at Olivetti, Alquati further explored and revealed the collective dimension of the contradiction. The employer has to encourage the workers in their ‘use value myth’, not only in order to ensure that the goods are actually saleable. The ‘myth of use value’ is at the same time the bosses’ most important means to enforce the production of surplus value in a political sense. (Here parallels with today’s propaganda of ‘total quality’ spring to mind). Without this ‘use value myth’ the companies would lose the workers’ ‘collaboration’.

“The high expectations of the worker in relation to both technology and the quantitative development of consumption are not fulfilled. This disappointment also results in the worker not being able to figure out whether the use value of the product he produces is in a decisive dialectical relation to other set aims, which he is left in the dark about. All this leads to continuous disappointments in his relation to and understanding of his work”. [24] Alquati continues: “If you ask both the ‘assembly worker’ and the ‘controller’ why things are organised as they are and what role they really serve, then most of them will answer that they have never understood it. One thing however is clear to all; namely that the controller actually hasn’t got the function of the high priest of quality, […] that the function of quality control still mainly lies with the assembly worker”. [25]

Alquati developed questions from this, which he then asked other workers. A few of these workers then started to do their own ‘little inquiries’: Who actually does the quality control? What role is served by the ‘faulty products’ that the controller rejects? Do the technicians and engineers know about this? Have they perhaps planned it? And what do the small managers do?

“This whole complexity finally leads to a fundamental discussion about exploitation, the rationalisation or ‘scientific work organisation’ and the bureaucracy – and about class struggle. The workers themselves often make a crucial mistake here. They set one work task as distinct and opposed to the other, and thereby set off the political mechanism that the company management have brought to life with these mystifications.” [26]

Alquati tries to criticise this opposition of tasks. If the workers say, for example “the controllers are unnecessary, in reality we do the quality control ourselves”, he then poses the question: “And what role do the controllers really serve then?” He works out that they are not there for the quality, i.e. the use value, but for the fulfilment of the plans that take care of the valorisation. How the plan is carried out, how they manage to produce use value in the given time, only the workers themselves know.

From these few quotes it becomes clear how Alquati and Quaderni Rossi make a decisive inversion in the direction of the inquiry. The workers are no longer the unconscious, to whom the socialists have to explain that capitalism is something very contradictory. But rather it is now about finding out, together with the workers, where, in the everyday conflicts, the potential for a common struggle lies. Even if the hypotheses of these inquires were often wrong in their detail, the fundamental thesis that the workers were not integrated and had not become ‘middle class’, but rather that they could still become the subject in class struggle, was confirmed in the 1961/62 strike movement.

Mistakes were often made where comrades tried to find a new, central subject or where the old intellectual (and Leninist) bad habits re-emerged, e.g. that one could understand class struggles in advance (“anticipate the class struggle”). Similarly, the whole argument about the ‘central figure’ is one of the worst legacies of Operaismo, and one that often prevents a real inquiry. Unexpectedly, one particular workers’ figure took on an important role in these struggles, one that the factory inquiries had not paid any particular attention to up to then: the young, unskilled worker who had migrated from the rural south, who was later simply referred to as ‘the mass worker’. However, on the basis of their previous work and in cooperation with emerging workers’ groups, the comrades could very quickly bring their theoretical work up to date, in line with the actual stage of class struggle.

Along with the new wave of strikes, a lot of interest in information and discussion developed amongst workers, which meant that the focus of the political work shifted. Conricerca now meant helping to spread information about the various struggles. The groups of ‘external’ militants ‘who got in touch with workers at the factory gates now saw their task in taking care of the ‘horizontal circulation of struggles’, for example, by distributing a leaflet or a newsletter with information about a small strike in one factory to workers in other factories in the same region. Or to make a strike in one department known to workers in the whole factory. Comrades made an effort to include workers themselves in the editorial groups of these publications. A then militant from Potere Operaio biellese [Workers’ Power, Biella region] described the role of these ‘externals’ like this: “We were the postmen of the workers”. And Guido Bianchini from Potere Operaio veneto-emiliano [Workers’ Power, Veneto-Emilia region]: “We wanted to help to spread these struggles, to break the old structures… We went to the factory gates, but not to preach, we didn’t want to be the party that sets the tone. We asked the workers what they wanted”. [27]

During the specific political situation at the time, this approach became very fruitful. It brought militants from various different political organisations together. Consequently the groups were not politically homogeneous, but the common reference to the working class movement made it possible to work together.

Intervention and organising

When Quaderni Rossi formed they broke only partly with the official institution of the ‘labour movement’. For example, Alquati presented the paper about the ‘new force at Fiat’ at a congress of the PSI. The confrontation around the ‘class union’ and the different opinions about the role or tasks of the party characterised the inner discussions from the beginning and soon led to the formation of factions.

Initially comrades in Torino still cooperated officially with the local branch of the metal workers union, who were politically at a dead-end and were hoping for some new ideas. In the first issue of Quaderni Rossi, a few union activists had signed their articles with their full names, for example Vittorio Foa, who only shortly after didn’t want anything to do with the ‘extremists’ from Quaderni Rossi. Cooperation with the union entered into a crisis when a part of the editorial group supported the wildcat strike of the maintenance workers at Fiat in the summer of 1961. The union ‘finalised’ the break with the group after the events on the Piazza Statuto in Torino in July 1962.

In May 1962, Panzieri formulated the tasks of the group in a letter to the editorial member Asor Rosa: “I believe that we have to put the strike over the collective agreement of the metal workers at the centre of our work […] I am more and more convinced that there are possibilities for a revolutionary line. But we have to get rid of the last remnants of our ‘minority’ complex and carry the spark, the search for a new strategy, into the crisis of the organisations. This is even more vital for us as we don’t want to be a small sect that is in possession of the truth, but rather militants who make a valuable contribution to the necessary new organising of the working class, a problem that is facing thousands of militants at the moment, including those who remain within the organisations. In my opinion we have to revise, modify, and if necessary totally change, our instruments of intervention. […] We can see the emergence of a new workers’ movement, but preparing a strategy for them is not a spontaneous process. The fact that we are able to see this new movement defines our tasks today, tasks that are really new. The features of the figure of the collective worker are not simply hidden within the heart of capital, he can only become conscious himself in his own way and collectively. These features are anticipated within the struggle and within the struggle the unity and revolutionary potential grows […]. It is about finding some forms of mediation. Because by distorting workers’ struggle and presenting it as a knee-jerk reaction to capitalist development, capital suggests strategies that will lead workers to failure. The ‘new’ potentials for revolution do not arise from capitalist planning, but from the anticipation-reversal of the decisive elements of capitalist planning by the workers”. [28]

Despite this anticipation, the group was surprised by the dimensions of the proletarian rage that erupted in July ’62 in the three-day street fight. Before the beginning of the metal workers’ general strike, Quaderni Rossie had suggested a public meeting together with the PSI, but this did not happen. Then they put their own call out to the Fiat workers that began with the sentence: “Fiat workers, behind your back and without asking you, the union organisations, in the service of the bosses, have signed a separate pay and conditions contract, in order to liquidate the workers’ struggle and workers’ power at Fiat…” (See the full text at the end of this article). The fact that in the text the unions were attacked apparently without distinction, i.e. that no distinction was made between the Fiat-run union and the ‘left’ union, got the unionists in the group into a lot of trouble. After the PCI press attacked Panzieri personally as an ‘extremist provocateur’, he made a u-turn and condemned the street fight as “damaging to the actions of the working class”. This did not represent the opinion of the rest of the group.

The part of the group around Negri interpreted the events in the Piazza Statuto as the working class breaking with the institutional labour movement (unions and parties), as an expression of the autonomy of the working class that now stood without representation. The leading article of the first issue of the factory newspaper ‘Gatto selvaggio’ [Wildcat] was entitled: “Through acts of sabotage the struggle continues and organises its unity”. Panzieri severely criticised this position. He criticised the Gatto selvaggio newspaper for their positive evaluation of Piazza Statuto and the “raw ideology of sabotage” and spoke about the “philosophy of the working class” in the paper by Tronti. In the years before his death in 1964, Panzieri’s position swung back and forth. Despite all the rhetoric he didn’t want a direct confrontation with the historical organisations of the working class. He rather saw the new role of Quaderni Rossi as a long term calculated forming of revolutionary cadre and was explicitly opposed to any rash or hasty party founding projects.

A political party of the class?

Within Quaderni Rossi there were three tendencies, which had managed to work together during the initial enthusiasm of the first two issues of the magazine. By the time the third issue appeared, it already featured two separate editorials. When the development of struggles required a decision about how to intervene politically, the group split.

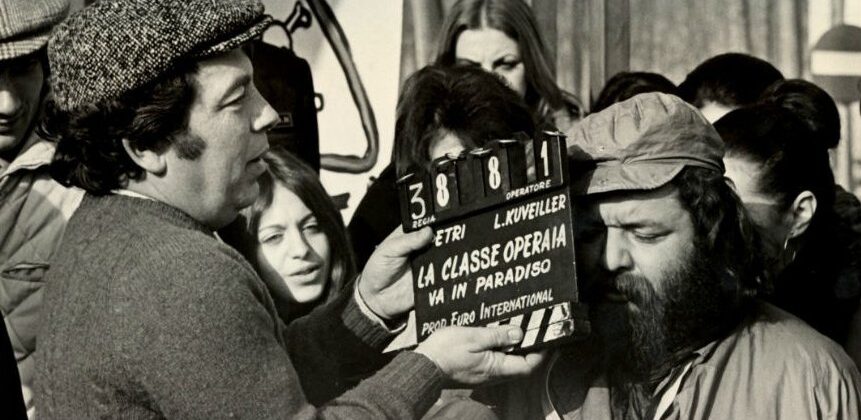

The group of ‘politicos’ (who later on became the theoreticians of the ‘autonomy of the political’, advocating the take-over of state power via the PCI), the ‘wild ones’ (representatives of the factory newspaper Gatto selvaggio) and the group around Negri came together to start the project ‘Classe Operaia’ [Working Class], a newspaper that targeted workers’ militants directly rather than the intellectuals and party and union officials. [29] The leading article in the first issue, ’Lenin in England’, by Mario Tronti [30] puts the question of the political organisation of the working class on the agenda. In contrast to the orthodox (Marxist Leninist) notions of organisation, Tronti deals with the question on the level of tactics:

“Capital, at this moment, is better organised than the working class: the choices that the working class imposes on capital run the risk of giving strength to capital. […] In particular, the working class has left in the hands of the traditional organisations all the problems of tactics, while maintaining for itself an autonomous strategic perspective free from restriction and compromises. […] The history of past experiences serves only to free us of those experiences. We must entrust ourselves to a new kind of scientific interpretation. We know that the whole process of development is materially embodied in the new level of working class struggles. Our starting point might therefore be in uncovering certain forms of working class struggles which set in motion a certain type of capitalist development which goes in the direction of the revolution. […] But this practical work, articulated on the basis of the factory, and then made to function throughout the terrain of the social relations of production, needs to be continually judged and mediated by a political level which can generalise it. […] These are impossible objectives for us at this stage of the class struggle: this is the stage where we must embark on a discovery, not of the political organisation of advanced vanguards, but of the political organisation of the whole, compact social mass which the working class has become, in the period of its high political maturity — a class which, precisely because of these characteristics, is the only revolutionary force, a force which, proud and menacing, controls the present order of things. […] And in place of the bureaucratic void of the general political organisation, they substitute the ongoing struggle at factory level — a struggle which takes ever-new forms which only the intellectual creativity of productive work can discover. Unless a directly working class political organisation can be generalised, the revolutionary process will not begin: workers know it, and this is why you will not find them in the chapels of the official parties singing hymns to the ‘democratic’ revolution. The reality of the working class is tied firmly to the name of Karl Marx, while the need of the working class for political organisation is tied equally firmly to the name of Lenin.” [31]

After one year it was clear, at least to the Rome faction, that this party could only ever be the ‘class party’, the PCI, renewed by ‘trade union-ification‘ and the ‘factory communists’. In the end Tronti’s revolutionary reversal of the levels of strategy and tactics ended up contributing to a very traditional concept of organisation. After the Rome faction had left the editorial group of Quaderni Rossi after the 3rd issue, Panzieri continued working with the ‘sociologists’ and other comrades from Turin. They had major illusions that they could continue the old inquiry project – and always with major fears of becoming marginalised as a sect. The political discussion took place mostly with the union and the PSIUP, the branch of the PSI that split from the party in 1964 over the question whether or not to take part in government. Some of the editorial group members had joined the new party.

Both groups that left Quaderni Rossi dissolved within two years, a few years before the new student and workers’ movement struggles in 1968/69 completely changed the situation in Italy. But, as political tendencies, they had a lasting and rejuvenating effect on the wider political debate. Many of their methods, political approaches and thoughts were only taken up later, and only years later it became clear how valuable they were. Many of the experiences and documents from this period have been lost and could be of great benefit, even today.

This leaflet was distributed by the Quaderni Rossi comrades at the Fiat gates on the evening before the metal workers general strike over the national collective contract in 1962:

—————-

Fiat Workers

Behind your back and without asking you, the union organisations, in the service of the bosses, have signed a separate collective contract, in order to liquidate workers’ struggle and power at Fiat. Now it is your turn to decide and to explain what you want and what you don’t want. We have to clarify what that bosses’ strategy is and what the workers’ answer should be. The position of the Confindustria (employers’ association) and the state owned enterprises is clear: the Italian bosses are prepared to make minimal concessions and demand in return that there will be no real workers’ struggles in the next three or four years. In the last few days the workers’ struggle has exposed this strategy of the bosses. It has made clear that the question of how workers’ struggle can develop in the next few years is on the table.

In Italy we see an intensive economic development that is supposed to bring the bosses immense profits, resulting in enormous increases in accumulation. A few days ago Valletta (president at FIAT) made clear that capitalism wants to enforce the control over a stable economic development, both within and outside of the factory. In the struggle today the workers’ movement stands at a crossroads: either the capitalist power consolidates itself, its capriciousness and its despotism, or the working class rediscovers its own power and organises itself against capital. The working class determines the conditions within which decisions are made, the conditions for the wider development of capitalism, right up to its complete defeat.

Fiat Workers

Fiat is decisive in the struggle today, because the metal sector is at the centre of capitalist expansion and Fiat is at the centre of this sector. Precisely for this reason the workers at Fiat face the decision to either go back to a situation of isolation where the bosses despotism once again has a free hand: the speeding-up of the work process, arbitrary qualifications and skill grades, redundancies, relocating workers, all summarised as the intolerable despotism of the Fiat company against the workers; or whether to become the conscious vanguard of a strong and unified working class.

Fiat Workers

The plan of the Italian bosses looks like this today: they want to divide the immense struggle of the Italian metal workers, by separating the contract negotiations of the state companies and the private companies and forcing through an in-house contract at Fiat. If they are able to enforce this before the working class at Fiat has reached their decision then this big struggle will be split. This struggle is so important for the entire class. And Italian capitalism, which the workers struggle has brought into such difficulties, will again be able to push ahead with the project of its masterplan.

Fiat Workers

Today you hold it in your hands to make the bosses plan fail. You are no longer isolated from each other and no longer isolated from the rest of the Italian working class. Your slogan has to be: no stepping back on the way to unity in the struggle of all Italian metal workers. You have already fulfilled the first and decisive condition of defeating capital. Faced with the power of your unity, capital is weaker than you. In your hands lies not only the key to today’s struggle, but the key to the future of the struggle of the Italian proletariat.

Fiat Workers

No-one but you yourselves can hit back at the bosses’ manoeuvres, that multiply in order to isolate you and make you powerless against the power of capital. Every bosses’ manoeuvre and every decision that you face, you have to confront collectively. In the last few weeks your protest has become an organisation. It was, at the least, the beginnings of a workers’ organisation. You have spontaneously found each other, to discuss, to reach decisions – group by group, department by department. You have gone to the works councils to discuss, rather than waiting for their decision. You have installed strike pickets at the right places, to discuss with the unsure colleagues and persuade them. That is the first form of a real workers organisation at Fiat. If you carry on with this organising then in the future you will never meet a struggle unprepared. No bosses’ manoeuvre could defeat your power.

Fiat Workers

The company management is worried that these forms of organisation are getting stronger, that they can really attack the bosses’ power in the factory. That is why they have, together with their (union) slaves, agreed to the current separate contract that doesn’t actually touch on any of the existing questions about the working conditions in the factory. With this everything is clear: the decision lies with you. You have to take your fate in your hands. This strike is a big opportunity to take a step forward in the organising of the class. You will come out of this struggle with an organisation in every group, in every department, in every Fiat plant. With a workers’ discipline that is capable, in every moment of exploitation, of standing against the despotism of the bosses and their lackeys.

Footnotes

1.

As Bologna describes himself in the title of an article in the journal “1999”.

2.

Quote from: Sergio Bologna, ‘Zur Analyse der Modernisierungsprozesse’ [An analysis of the modernisation process]. Introduction to the lecture by Antonio Gramsci’s “Americanismo e Fordismo”, Paper of the Gramsci conference on 29-30 April 1989, Hamburg Institute for Social History of the 20th Century. [Hamburger Institut für Sozialgeschichte des 20. Jahrhunderts], working paper No. 5, Hamburg 1989. On ‘workers’ medicine’ see the article by Sergio Bologna in Wildcat 56 [German only].

3.

Karl Heinz Roth (Hrsg.), Die Wiederkehr der Proletarität. Dokumentation einer Debatte, Köln 1994. [The return of the proletariat, Cologne, 1994]

4.

Guido Bianchini, Interview November 1994, Padova.

5.

Dario Lanzardo, La Rivolta di Piazza Satuto, Torino, Luglio 1962, and Milano 1979.

6.

Romano Alquati, Camminado per realizzare un sogno commune, Turin 1994 (Velleità Alternative), page 161.

7.

Romano Alquati, Sulla Fiat, Vorwort, Mailand 1974. Translated into German in Thekla 6.

8.

Claude Lefort, L’expérience proletaire, in: Socialisme ou Barbarie, Nr. 2, 1952. In the German version of this text, here and in the following quotes from the Italian translation in Collegamenti 2-4, Mai 1978. For this English version we have, where possible, translated from the French original.

9.

Danilo Montaldi, La mistica del “selvaggio” (1959), in: Bisogna sognare. Scritti 1952-1975, Mailand 1994, Page 364. Or a new recent article: https://newleftreview.org/sidecar/posts/montaldis-notebooks?s=03

10.

Raniero Panzieri, Spontaneità e organizzazione. Gli anni dei “Quaderni Rossi” 1959-1964. Selected writings, published by Stefano Merli, Pisa 1994, Page XL.

11.

Raniero Panzieri, Lettere, Venezia 1987, page 256 onwards.

12.

Alquati: Die neuen Kräfte bei Fiat [the new forces at Fiat], in: Alquati (1974).

13.

Toni Negri, Dall’operaio massa all’operaio sociale, 1979, page 48 onwards.

14.

Guido Bianchini, Interview with Gabriele Massaro, March 1991.

15.

Speech in Torino, November 1994.

16.

Romano Alquati, Sulla Fiat, Introduction, Milan 1975, page 13.

17.

Ibid.

18.

Raniero Panzieri, Uso socialista dell’inchiesta operaia, in: Raniero Panzieri, Spontaneità e organizzazione, Pisa 1994.

19.

Raniero Panzieri, Il diario di un operaio di Daniel Mothé, in: Panzieri (1994), page 17.

20.

This paragraph is the summary of a paper from the workers circle ‘militant inquiry’, that was published [in German] in Thekla 8. “Organic composition of capital and labour force at Olivetti” Organische Zusammensetzung des Kapitals und Arbeitskraft bei Olivetti was first translated into German in 1974. This text fell into our hands at the beginning of the ’80s and was one of the most important discussion papers for the Karlsruher Group [the pre-cursor to the Wildcat group].

https://viewpointmag.com/2013/09/27/organic-composition-of-capital-and-labor-power-at-olivetti-1961/

21.

Alquati, Olivetti, page 109.

22.

Ibid.

23.

Ibid. page 181.

24.

Ibid. page 174 onwards.

25.

Ibid. page 175.

26.

Ibid. page 175 onwards.

27.

Guido Bianchini, Interview, November 1994.

28.

Raniero Panzieri, Letter to Asor Rosa, 10th May 1962, in: Lettere (1987), page 330 onwards.

29.

In Thekla 6, that unfortunately has been unavailable for years, we had published in German some some articles from Classe Operaia by Romano Alquati.

30.

Classe Operaia No. 1. translated [to German] in: Balestrini/Moroni, Die goldene Horde, Berlin/Göttingen 1994.

31.

Balestrini/Moroni (1994), page 93-100.