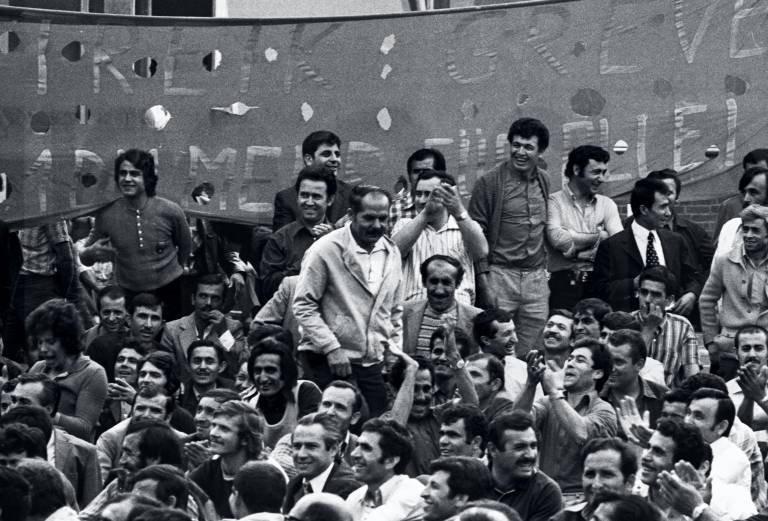

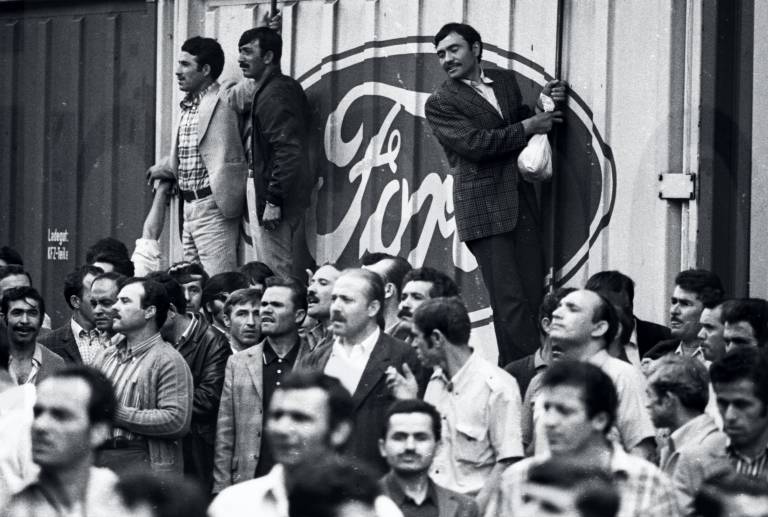

On the 24th of August 1973, a wildcat strike began at the Ford car plant in Cologne, Germany. Below you can find a conversation with Hasan Dogan. Hasan Dogan was a member of the twelve-member strike committee, alongside Baha Targün, the now deceased strike leader.

By Yusuf As

In January 1973, strikes had begun in the metal and steel industries and there were also strikes at the shipyards. The poor working conditions had been the straw that broke the camel’s back. A strike wave started to form, each strike triggering another dispute. In winter 1973 strike researchers counted more than 300 walkouts involving more than 300,000 workers in western Germany. Two particular struggles had caused a stir in the area around Cologne. First of all the women workers’ strike at the automotive supplier Hella in Lippstadt and at Pierburg in Neuss. Women of different nationalities were fighting for “equal pay for equal work”, for the abolition of the low wage category 2, which was only for women. The women were victorious in the end.

(We can see the international dimension of these type of disputes, if we think, for example, about the women workers’ strike at Trico in west London in 1976. For some of us AngryWorkers there are also biographical parallels, as for example, one of our grand-fathers worked at the Ford Cologne plant during the strike, while another grand-father worked as a Punjabi migrant worker at the Lucas car battery plant in the UK. Both of them were certainly no militant workers, unfortunately. Another AngryWorker was a car worker in UK factories himself during the 1970s and knows all about encouraging unofficial action!.

The strike broke the state’s attempt to keep workers from Turkey as the ‘eternal foreigners’, who were not allowed to bring over family or to stay in Germany if they were not working. In this sense the strike played a similar role like the Grunwick strike in the UK, although, and that’s a big difference, it didn’t get the support of the official labour movement. Still, after the 1970s the IG Metall union opened up and integrated many of the former ‘workers’ rebels’ from Turkey into the lower ranks of union officials.

An ironic fact about this strike is that comrades from autonomist groups around the ‘Wir wollen alles’ (‘We want everything’) network, some of whom had worked at Ford, had ‘given up’ on Ford workers and had started focussing on housing struggles by the time the strike kicked off.)

When did you start working at Ford, and did you already have contacts to other workers?

I got a job there about three months before the strike. At that time 32,000 people were working at Ford, 12,000 of them from Turkey. In some halls were up to 90 percent people from Turkey. We mostly did the dirty work. I got to know the militant workers relatively quickly. Baha Targün, the figurehead of the strike, I met him as soon as I arrived. We became friends. Baha knew many in the company and was a respected worker. He was very well connected. We often discussed our situation at the plant and in the dormitories. (Initially so called ‘guest workers’, mainly from Turkey, had to live in isolated barracks, often with a curfew imposed by security)

In 1973 there were countless strikes. You joined them only in August. Why so late?

When the wave of strikes broke out in West Germany, one company after the other joined the struggle. Left-wing groups tried to mobilize at Ford in Cologne as well. Flyers were distributed at the gates with the call, “When is Ford on strike?” The plant was firmly in the hands of IG Metall (metal union, biggest industrial union globally) and the works councils, who wanted to prevent any strike and cooperated with the management. So there was no strike at Ford for a long time.

How did the strike come about? What were the preconditions?

We had very bad working conditions. Our dormitories were a disaster. We shared a small room with six men and had a shower for two rooms and a kitchen for three rooms. We worked in rotating shift-systems on a piecework basis. In addition, almost all of us were on pay grade four. Almost all of our German colleagues had pay group six or seven. After the summer vacation, the last straw that broke the camel’s back was delivered. Several hundred colleagues from Turkey were summarily dismissed after the vacations. They returned from vacation too late. For the most part, they had sick notes or explanatory excuses. Annual leave was a big issue for migrant workers. In those days, a one-way trip to Turkey by car took no less than three days. That’s why everyone wanted six weeks of vacation at a stretch. The longing for the homeland and the

family was very great. Many of them, like me, had left their wives and children behind to work here for a few years. Then hundreds of colleagues were sacked without notice, which meant that we had to continue to work with fewer people. But that wasn’t possible, we had already reached the limit. Then we had a big blowout.

What happened on the 24th of August?

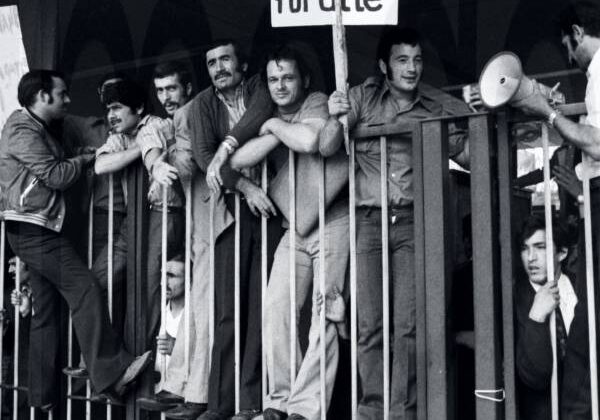

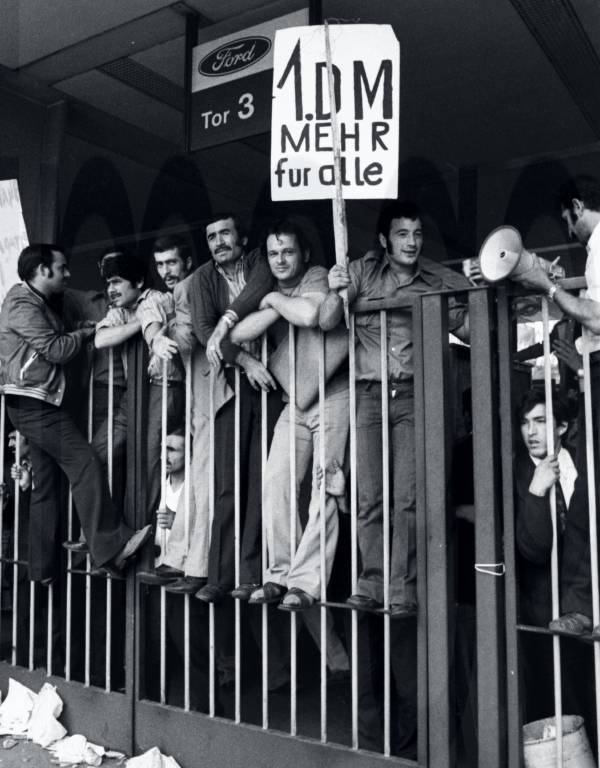

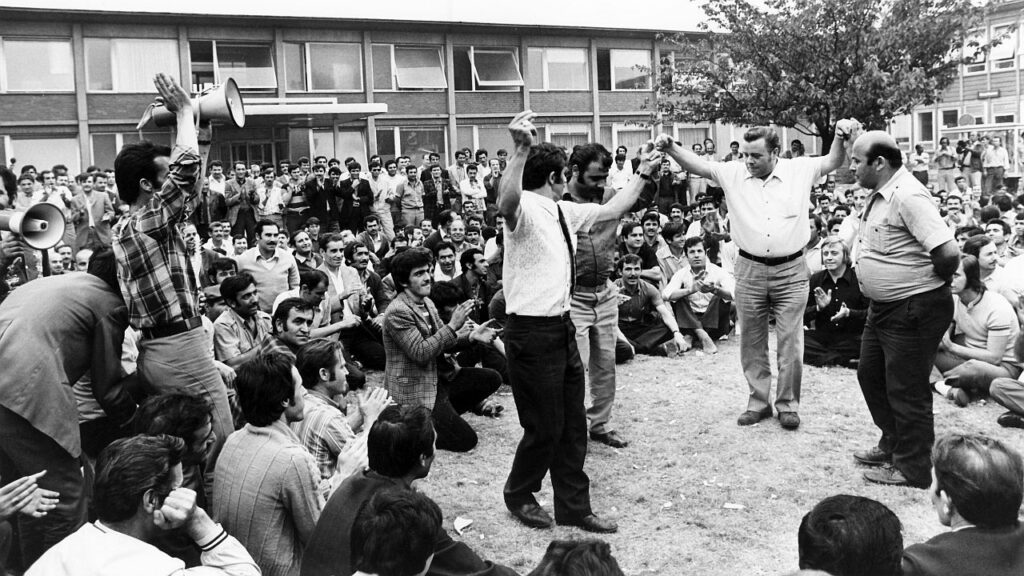

The time had come on the late shift. We were in the “hell” of Ford, in the Y-hall. We were supposed to do the work of the laid-off colleagues. We already didn’t follow the normal piecework. Then one of our colleagues suddenly lost his patience and started shouting. And immediately we all joined in. Baha had a very powerful voice. He shouted very loudly that we should demonstrate through the halls. We ran from department to department, all of us, arm in arm. Almost everyone joined us – mostly the people of Turkish origin, but also German colleagues. We walked out to the next hall and then over the bridge to the western area. When we arrived there, thousands of workers were behind us. We blocked all the gates. No one could get in or out.

What were your demands, and how did the works council and the IG Metall behave?

In front of the personnel department, we held a big meeting with the work-mates and discussed our demands: one Deutschmark more per hour (about 20% pay increase), six weeks’ vacation at a time, the reinstatement of the laid-off colleagues, and the equalisation of pay grades. Everyone agreed. IG Metall and the works council tried to hijack the strike and conducted negotiations without us. But we didn’t care. We had the power in the factory. We called the bureaucrats “satilmis sendika” (“bought unions”). The late shift then went home in unison, the night shift was canceled by Ford. On Monday, the strike continued with the early shift. But when we saw that the works council was on the other side, we formed our own strike committee and started our own negotiations.

How did the negotiations go?

The factory management tried to bribe us. We were promised millions of marks and cars were promised to us if we stopped the strike. The committee had the entire strike under our control. The factory management knew that, too. We refused and said what our demands were. If we had let ourselves be bought, we might as well have died. What would have been the point of living as a traitor?

What happened when your demands were not agreed to? Was there solidarity from outside?

As of Monday, we walked out again. We started to sleep in the factory. Word of our strike spread very quickly to the public. Everybody heard about it. They brought us food and drinks in trucks. Solidarity grew and gave us even more courage. On Monday about 400 colleagues slept in the plant, on Tuesday it was over 800, and on Wednesday well over 2,000. At that point, the management realised that things were serious and that there was only an end in sight if our demands were accepted. Even Willy Brandt (chancellor at the time) called on us to end the strike. We ignored him and did not listen. What kind of signal would that have sent to colleagues if we listened to the state.

On the fifth day, the strike was crushed. What happened?

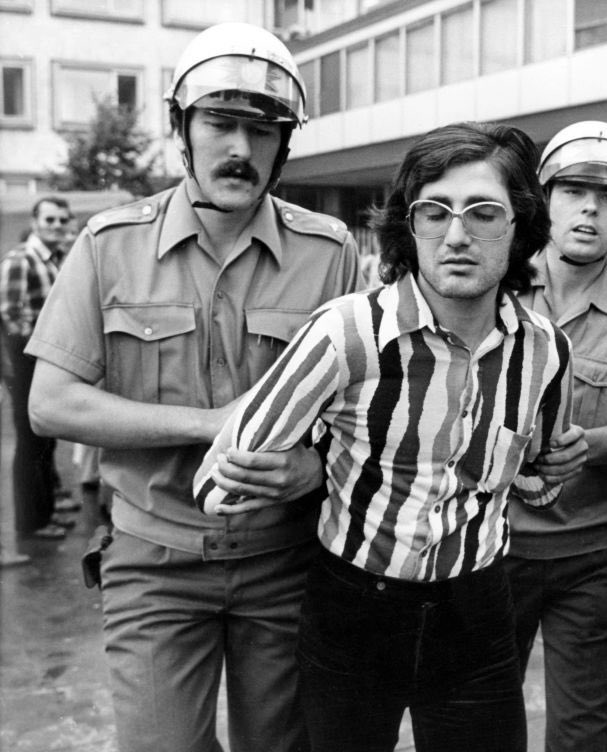

On Thursday, we walked the halls again to mobilise everyone. As we were approaching Hall G, we were met by a counter-demonstration. They provoked and attacked us. The management had called in the police and other people whom we could not identify. When we came out of the G-Halle, the gate was closed behind us. Suddenly we, the committee and a handful of other workers, were separated from the crowd. A big mistake on our part, which we had not seen coming. The police and the thugs beat us up and threw the strike leadership into the waiting car. Baha, they almost beat them to death. The remaining colleagues only got through one by one at small doors and there was a brawl between workers and police. The committee and a dozen of the leaders were arrested. When we left no one really knew what to do or how to proceed. What to do next. We didn’t expect that either. The strike was bloodily put down.

What happened after that?

We, the arrested workers, were all summarily dismissed. It is estimated that 250 to 600 workers no longer came to work. Some out of fear and many because of threats from management because they had participated in the strike. We were threatened with criminal charges and direct deportation. For some these threats became reality.

What did you achieve?

Our strike aroused great respect and fear on the part of the management towards the people of Turkish origin. We were no longer perceived as guest workers, but as workers. After the strike, a colleague said to me: “This is the day when we are no longer guest workers, but became workers.” After more than ten years, we still heard what traces our strike had left on those up there. As soon as management hears about discontent they come down to the shop-floor to try and appease things. We showed that we workers were a power and that nothing works in the plant without us. We didn’t get everything. But we did raise the awareness of thousands of workers about their situation.”

For further reading:

https://www.emarvakfi.org/seminar26022016-They%20called%20for%20workers%20but%20humans%20arrived.pdf

http://ford73.blogsport.de/materialien-texte/