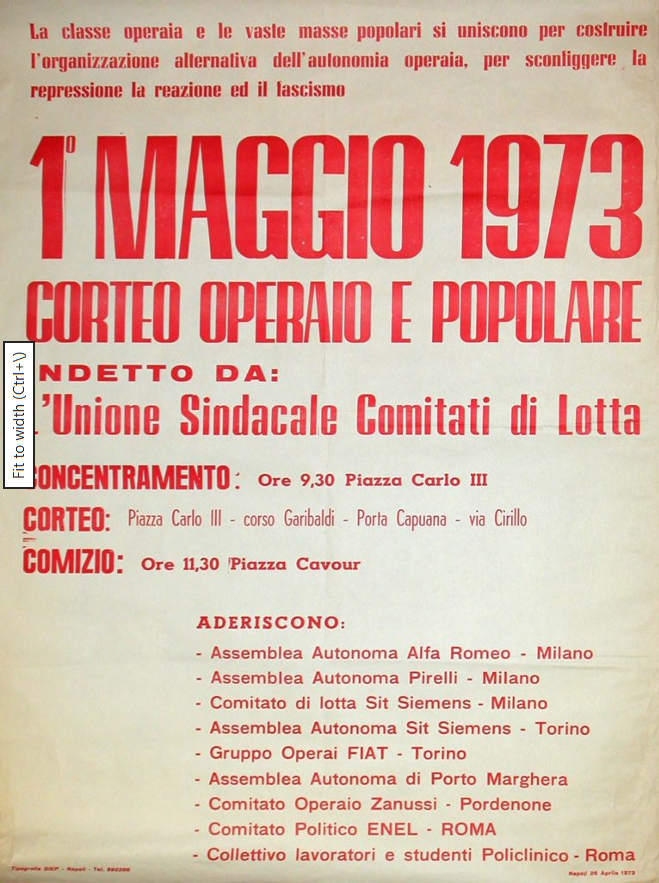

In the first part of this series we could read about the conflictual relationship between the main national extra-parliamentary groups of the far-left in Italy in the 1970s, such as Lotta Continua and Potere Operaio, and the political organisms of workers autonomy. In this part we document translations of two political proposals by three of the main autonomous worker organisations: the Autonomous Assembly at Alfa Romeo and Pirelli and the struggle committee at Sit-Siemens, mainly located in Milan.

These autonomous assemblies were the bridges between autonomous factory struggle, proletarian actions in the working class neighbourhoods and the wider political movement. In particular the work at Alfa Romeo was impressive, as this workers’ documentary, shot as a collective effort at the time, demonstrates. The collective at Alfa Romeo produced their own factory paper, ‘Senza Padroni’ (Without Bosses), analysing, amongst many other things, the current moment of bosses’ counterattack through repression and inflation; the lessons of the coup in Chile 1973; the situation of struggles in various factory departments; the question of workers’ health inside and outside the factory; the wildcat strike at Ford in Cologne; the outcomes of the conference of autonomous factory assemblies and the current activities of fascists at Alfa, including a list of their complete names and their places of work.

The comrades also published a 200 page diary of the main struggle at Alfa from 1972 to 1973, with concrete reports and wide-ranging analysis, including inquiries into the health conditions at the foundries together with medical doctor comrades; actions against housing evictions that target not only Alfa workers; self-defense against physical attacks by Communist Party trade unionists on the autonomous struggle; and reports on the collaboration with student committees. Here are two short excerpts that give a flavour of the intense activity of the comrades:

5th of January 1973

“Two comrades have been suspended for a demonstration at the company offices: they were part of a delegation of workers who went to protest about the management fraud concerning the 13th monthly wage. In the assembly department, the testing and the finishing department the first shift gets together to discuss a possible ‘checkboard strike’, which had been prepared by the official department delegates in the previous days. The participation in the assembly is solid, 300 out of 450 workers, and the interventions in the discussion are incisive. The comrade who started the discussion said: “We all know that a struggle like that can’t enforce a good result and we know that we can’t just continue complaining about the union. It’s up to us to come up with a form of struggle that is more effective.” The following numerous interventions speak in favour of the intensification of the struggle, linking it to the current political moment: the increase in prices, the repression, the need to beat the Andreotti government etc.. The delegates of the PCI attack the initiative of the assembly and the delegates who prepared the strike plan try to divide the workers with their usual hysterical denouncement of the ‘political groups’. These groups are the only forces that manage to give a voice to the demands from the shopfloor workers, which become increasingly pressing and which push for an intensification of the struggle.”

12th of March 1973

“The strike program: the strike begins at 9am and then there is a permanent assembly till 11pm, open for all political forces. By now 6,000 workers have been suspended. We distributed a leaflet that was decided last Saturday, which tries to mobilise the suspended workers to block transport of the finished products. We didn’t have a megaphone and didn’t manage to mobilise anyone until 9am. At the assembly we decided how to act. A comrade brought a red flag and the others talked to fellow workers, asking them to gather under the flag to block the transport gates. A comrade explains the necessity of such an action and a protest march towards the gates set off. In this way the transport of finished cars was blocked, while the assembly was reduced to empty talk from the trade union. At 12noon the assembly is suspended and the participation of workers in the afternoon is less solid. At the assembly, Ciccio Busacca, manual worker, singer and story teller from Sicily sings the ballad of Tiruddu Carnevale, a trade unionist who had been killed by the mafia in 1960. The picket at the gates is massive. At 6pm we have an assembly of all the people on picket to decide whether to call it a day or to continue. The reason to maintain the picket is that there is no other form of struggle that would allow us not to retreat from the bosses’ pressure and not to give up hope. In this regard the factory left, formed by the Autonomous Assembly, the Political Workers Collective, Group of Workers and Employees and individual vanguards are the political reference point for the workers. The motivation against the picket is the risk of getting isolated, given the lack of support by the trade unions. We decided to maintain the picket throughout the night and to mobilise more workers at the assembly tomorrow.”

The following two positional papers of the autonomous workers’ organisations at Alfa, Pirelli and Sit-Siemens were circulated in 1973. The first longer paper is called ‘Workers’ autonomy and organisation’, from February 1973. The second paper was published in Potere Operaio’s newspaper and was meant as a contribution to a conference of autonomous workers’ committees in December 1973.

In both papers the comrades of the committees and assemblies criticise the role of the ‘groups’, by which they mean external political organisations. They also criticise the politics of armed left-wing organisations, such as Brigate Rosse, without naming them. In the first text this critique is in the paragraph ‘Economic struggle and political struggle’ and in the second paper in ‘Workers’ interest’. They criticise the Brigate Rosse as separate ‘armed-wings’ that basically bolster trade union negotiations, but don’t question the separation in economic and political struggle. These parts are slightly cryptic, given the tense atmosphere also within the movement at the time. The comrades maintain the need for proletarian illegal struggle and mass violence.

———————–

Workers’ autonomy and organisation

Discussion paper by the Autonomous Assembly of Pirelli – Alfa Romeo and the Sit Siemens Struggle Committee Milan, February 1973

The employers’ counter-platform

The employers’ counterattack against the struggles that have been imposed by workers’ autonomy in recent years is at the centre of the current conflict; it tries to impose their restructuring project on the working class; it also wants to force the workers’ movement to fight from a defensive position. But we would be greatly mistaken if we thought that the points put forward by Confindustria (employers’ association) in the counter-platform were merely an act of provocation against the workers’ movement. These points (regulation of absenteeism; full utilisation of plant capacity; with new shift systems, which include bank holidays; regulation of strikes and company disputes) represent the cornerstone of a strategic line that employers intend to pursue, which already aims to achieve partial results, starting with the current collective contracts. Above all, this line of the employers explicitly refers to the responsibility of trade unions regarding their project of restructuring.

Trade unions and the works council

The trade unions are currently in the second phase of their process of integration. The first phase, which covers the entire post-war period, is the phase of national reconstruction of capitalist development. The second phase is one in which trade unions must engage more openly in a role of collaboration with the plan of capitalist restructuring and reformist development.

The current harsh attack by the employers with the counter-platform and the centre-right government has the main aim of stripping the trade unions and the parties of the working-class left of whatever rebelliousness still exists in them. They try to force the working class to take a position of absolute passivity towards the capitalists’ plan. In fact, faced with this attack, the trade unions negotiate the employers’ platform, they also call for productivity increases, and force the working class to limit its forms of struggle, just as demanded by the bosses. The counterpart to this blatant sell-off of the collective contracts and forms of struggle that the working class have conquered in recent years can only be, as demanded by the trade unions and the parties of the parliamentary left, the restoration of the centre-left government, linked to the continuation of a reform project that sees the parliamentary left more involved.

The role of the works council

We do not believe that the works council [consiglio di fabbrica] is the basic organisational tool that the working class has been able to impose as an expression of its growing autonomy. It is clear, however, that faced with pressure from the grassroots, the growth and development of workers’ autonomy, which in its spontaneous phases often escaped the control of the trade union leadership, the works council was forced to give way to a more grassroots model of organisation, which at the same time gave them greater control over the grassroots itself. Taking stock of the establishment of the councils to date, we cannot but note that they have always been sufficiently controlled by the union leadership. The unions allow the councils to function when they ratify what has already been established by their own line and block them as soon as grassroots demands prevail. We have seen how, during the drafting of the metalworkers’ bargaining platform, a whole series of positions put forward by the major Milanese factories were cut out at the final stage of the Genoa conference.

We see this more clearly now, when faced with the decision of the union leadership to curb the struggles. The unions back down whenever the bosses implement their forms of repression, which leaves the instrument of the factory councils virtually powerless to push through a position of resistance.

To look religiously to the factory council as an ideological model, the only point of reference for the organisation of the working class, means, realistically, submitting to the plan of the union leaders to expropriate all decision-making power from the workers’ assemblies and all forms of organisation that directly express the struggles for workers’ autonomy. The process by which the organisation of workers’ autonomy is realised and advanced must be the opposite: it must start from the workers’ ability to directly decide and implement the forms of struggle and objectives suitable for defeating the union line.

We must reduce the space for any mediation that aims at castrating the direct action of the working class. This does not mean that the existing reality of factory councils should be ignored, but that we must try to intervene in this space, to push through the line expressed by the working class. However, we want to reiterate how erroneous and castrating an attitude of absolute subordination of direct working-class action to the decisions of the factory council is. If anything, the process should be the reverse: that is, direct workers’ action should influence the council and the trade union. In this sense, the creation of departmental workers’ committees, linked together within the factory, are essential at this moment. They have to express the will of the rank-and-file, to which they must provide the means for immediate implementation of their decisions.

Restructuring and absenteeism

Restructuring is capital’s response to class struggle; it also represents an adaptation to the needs of capitalist development as a result of the unification of several monopolies and the need to convert plants due to the saturation of certain markets. It is clear that, from the employers’ point of view, this whole process must be carried out at the expense of the workers.

The working class’s response to this plan by capital must move in two directions: one must be represented by an attack on the productivist structure of the organisation of work. In fact, when restructuring is used to increase production, leading on the one hand to an increase in the workload for some workers, and on the other hand, layoffs and massive redundancies for others, the best response must be to move from a phase of absenteeism (a moment of legitimate individual defence against harmful conditions and work rhythms) to a more politically conscious form of refusal to work. This refusal must be achieved through a policy of permanent non-cooperation, articulated in the refusal of piecework, the reduction of work rhythms and the refusal of harmful work. A genuine anti-productivist consciousness must arise among workers, in which there must be a clear demarcation between the interests of production and capitalist profit and the interests of the working class. The other element of the workers’ response to restructuring is to set themselves the goal of a guaranteed wage. The emphasis should not be placed on the demand for job security, but rather on the right to life, in the form of a guaranteed wage. It is clear that this goal is intended as a response to dismissals and suspensions and has real significance to the extent that it is generalised and concretely articulated in various situations.

The Andreotti government and our political program

The centre-right Andreotti government is intended to be a harsh response by the bosses to the attack that workers’ autonomy has been waging in recent years. We are all aware of the repressive measures that have characterised the current government: from the reduction in pension increases to the massive extension of the redundancy fund, from the attack on pickets to the thousands of legal charges against workers, from the reduction of democratic spaces for demonstrations etc. to the attack on democratic magistrates, the increase in police contingents, the presentation of the bill on police detention, and even the licence to kill for police officers.

It is clear that the overthrow of the Andreotti government, as the advanced and acknowledged point of the bosses’ repression, which has been put in place specifically for the season of collective bargaining, must be one of the objectives that the working class must set itself. But above all, it must be clear to the working class consciousness that any government put in place by the bosses, whether centre-right or centre-left, will respond with the same repressive tools when the class struggle threatens the privileges on which capitalist power is based. The Andreotti government has tasks to perform, tasks that are part of the strategic necessity of the system: restructuring, control of the working class at the point of production, the annihilation of subversive forces, the alignment of the trade unions. These are strategic necessities of the system, not a personal whim of Andreotti. Any government will have to fulfil these tasks, it may do so in a more or less elegant and efficient manner, but it will do so.

Therefore, the slogan “bring down the Andreotti government!” risks confusing the essential point above and becoming an opportunistic diversion, a false political objective. Furthermore, in the specific case of bringing down the Andreotti government, we must be careful not to push against an open door. In fact, our assessment of the trade unions’ sell-out of collective contracts and forms of struggle, in full agreement with the parties of the parliamentary left, could already foresee a return to the centre-left as a quid pro quo from those in power. In this sense, acting as a catalyst for the fall of the Andreotti government without at the same time questioning, through struggle, the capitalist system of production itself, means playing into the hands of those forces that aim only to take the working class from a more rigid cage to a more reformist cage, without however giving space to the revolutionary alternative.

Antifascism and class struggle

In this sense, the whole hypothesis that has been given a lot of airtime in recent times, namely to create a unified discourse and organise a hard struggle on the basis of anti-fascism, as a stimulus for the overthrow of the Andreotti government, risks being a misleading objective. On the one hand, because it is giving the movement a character of symbolic militancy [caratterizzazione manifestiola], which then leads to the emptying of the movement itself. On the other hand, the idea of a unified and at the same time hard-line struggle ultimately becomes, due to the approach that has been taken, increasingly unified and less hard-line, and increasingly recoverable by reformist organisations.

Above all, we cannot make something that is a partial objective of class struggle the focus of the struggle itself. This would run the risk of falling into the reformist trap. There can be no growth of anti-fascist struggle unless it starts concretely and organically from the class situation and unless it is articulated in objectives that are at the same time anti-capitalist, i.e., attacking the organisation of work (against harmful conditions, work rhythms, productivity, qualifications) and society (rents, prices, transport, etc.); and if it is not expressed in the forms proper to proletarian struggle that goes beyond the legal straight-jacket [illegalitarismo proletario]. Therefore, at a time when the situation is effectively difficult within the factories, due to the union’s openly obstructive position with regard to the struggles, we must be careful not to fall into suggestive pseudo-radical escapism [fughe manifestaiuole], which is ultimately a bubble that bursts at the first impact: the result of this tendency is the external and intellectualist direction of the movement, which finds its organisational tendency in the political ‘groupings’.

Characterisation of the organisation of the workers’ autonomy

The correct development of workers’ autonomy must move along three lines:

a) It has to have an anti-capitalist and anti-productivist nature, meaning, it has to attack the structure of work, as the objectives that the movement sets itself.

b) The non-legalistic terrain, which is linked to the needs of the struggle, is conditioned only by the awareness of our balance of power.

c) The capacity for self-organisation of the struggle, in all its aspects, has to be developed continuously and be conducted directly by the exploited masses themselves.

In this sense, autonomous organisations must not assume a role of bureaucratic representation of workers’ autonomy, but rather perform a dialectical function of constant overall political guidance and organisational accumulation of revolutionary action with respect to the movement.

Collective contracts and social struggles

One of the reasons why the factory struggle finds it difficult to express itself in all its harshness derives not only from the restraining action of the trade unions, but also from the ever-decreasing credibility that collective contract struggles are assuming in the eyes of the workers. After the collective contract struggle of 1969 and the remarkable advance of the movement in the factories, with the achievement of considerable gains, the limitations of such a struggle became apparent when it was detached from the social context. It is precisely on the wider social front that the bosses have had their revenge, as demonstrated by the continuous increase in the cost of living. The trade union is trying to respond to the working class’s need to broaden the struggle to the social arena, inserting itself with its proposal for a struggle for structural reforms, pursuing the idea of reconciling the interests of employers and the exploited class in the path of capitalist development. The only outcome of all this is interclass collaboration.

Today, the struggles against the cost of transport, for the right to housing through the occupation of empty buildings and through strikes by squatters, are all moments of proletarian struggle on the social front. It is important to build on these moments of partial and direct attack, outside the factory, to create comprehensive organisations managed by the proletarian base and linked to the struggles in the factories, taking impetus from the current collective contract struggles and in response to the pay cuts resulting from the strikes.

Today, the situation is ripe because, on the momentum of the struggles around collective contracts and in order to give them more oxygen, a programme of struggle can be launched on unifying objectives between the various job categories and for the whole proletariat on the social terrain, opening a direct dispute with the state. This platform must have its roots in factory objectives, starting with the attack on production and the opposition to negotiating over the employers’ counter-platform. This is important to prevent a division in the collective disputes between private employers, state employers and small employers, and to block any attempt to impose self-restraint on the forms of struggle.

On a more specifically social level, the programme must move forward on the basis of unifying objectives in the struggle against prices, based on specific demands such as rent reduction for all, rather than housing reform; payment of transport costs by employers; elimination of payroll taxes; and non-payment of utility bills (electricity, gas, etc.).

In terms of objectives that oppose the strengthening of the state, the proposal for the Special Police Laws [Fermo di Polizia] must not be allowed to pass, and any tendency to increase the repressive capacity of the state structure must be fought (e.g. the removal of the three Milanese magistrates who correctly interpreted the Workers’ Statute).

Pursuing such a programme also means setting the goal of bringing down the Andreotti government, but on a very specific basis of anti-capitalist attack on the very structure of exploitation.

Localism or general organisation

The development of autonomous bodies to address the needs expressed by workers’ autonomy correctly must be based on three principles:

1) The leadership of the struggle in the factory, in all its implications, and outside the factory, through direct links, must be with the workers themselves and their capacity for self-organisation.

2) The autonomous organisation must be able to unite the economic struggle with the political struggle, through its objectives, in its organisational moments and in its strategic line. It has to reject the reproduction of the separation which is typical of traditional workers’ organisations, all of which have ended up reformist, between the trade union on the one hand and the party on the other.

3) The autonomous organisation must be central to the development of an overall political line that strategically opposes the plans of capital, attacking it with a revolutionary trajectory. This has to happen from within the class situation and under the direct control of the workers’ leadership,

It is clear that in order to perform this function correctly, increasingly stable links must be established between the various autonomous bodies, in factories and in the social sphere, which emerge from the class situation. This connection, which must always be made directly and not through a political group specialised in this sense, contributes to mutual growth. This growth allows us to mature in terms of content in the individual internal situation and aims at a correct homogenisation towards the same strategic line.

Perhaps this project will take longer than others, but we are convinced that it is capable of building on concrete foundations. The reverse process, that of imposing a priori the choice of a strategic line by a substantially external structure, would empty the workers’ autonomy of its revolutionary potential. It would deprive the workers’ leadership of the control over and verification of the organisational framework.

Economic struggle and political struggle

The separation that traditional left-wing organisations, such as trade unions and parties, reproduce between economic struggle and political struggle, is a division that leads to progressive integration into the status quo. The separation has been widely criticised by the rebirth of the revolutionary movement in recent years. Today, however, the old practice is in danger of being reproduced, albeit in new and more updated forms. The revolutionary groups risk becoming bearers of this tendency to the extent that they reproduce the old logic, when they want to entrust autonomous mass organisations with a more economistic role of subordination to the general political line of the group itself.

The reproduction of the old pattern, albeit in a new form, between economic struggle and political struggle, tends to lead the movement back towards integration, or towards a new type of adventurism, depending on the line of tendency that most characterises it. It becomes adventurism when the development of the movement is pushed along essentially syndicalist lines, masked by appropriate revolutionary language. This line essentially leverages a legalistic space, which is to be progressively enlarged by nibbling away at the system. In reality, this tendency has the effect of frightening the bosses and committing them to a very harsh repressive response, which the class movement as a whole is not prepared to react to at the level of confrontation decided by the bosses. Even by prioritising the political armed struggle over the mass movement, there is the same risk of precipitating repression on the unorganised class, at the level of confrontation provoked by the armed revolutionary group itself.

In this sense, it is right that autonomous organisations should move along a line that unifies the political and economic struggles. They have to take overall responsibility for the organisational requirements according to the level of confrontation of the working class, in all areas in which they operate, including that of proletarian illegality.

Class struggle and direct action

The revolutionary process passes through direct action. Current laws are the result of the consolidation of a certain social structure based on the power of one class over another, whose privileged conditions require violent force (police, judiciary, fascists, etc.) to maintain strict respect against those who are exploited and therefore rebel. Within this structure, a margin of apparent mobility (bourgeois democracy) is granted, the result of previous struggles, whose limit is not to question, not with words but with deeds, the conditions of the privileged class.

A movement that does not propose the illegality of the struggle in a strategic and not just tactical sense can never have a revolutionary function. This is where the debate arises amongst those who have accepted the illegal and non-reformist path: whether it is about mass violence or violence detached from the masses. None of the participants of this debate will ever be willing to declare that the proletarian violence they exercise is outside the masses. Therefore, in order to verify whether an act of political violence is performed by an armed wing or not, whether it is an abusive self-appointment of representatives of the illegal proletarian struggle or its natural expression, we must establish criteria for evaluation.

The first criteria we have already highlighted above: the proletariat must act not in accordance with bourgeois laws, but in accordance with the convenience of its own struggle. To establish the criteria for judging the convenience of the proletarian struggle, we rely on the following:

a) that the action arouses support, approval, participation and reproduction among the masses, achieving the goal of a greater radicalisation of revolutionary consciousness.

b) that action is taken with a sense of justice and proportion when striking those actually responsible for the repression of workers (you don’t break an egg with a hammer!).

c) that the damage caused to the bosses’ structure is proportionate to the capacity, both in terms of consciousness and organisation of the working class, to react and counterattack in response to the bosses’ repression.

d) that any actions must be coordinated with general political action, i.e. they must be internal to the class struggle, in the sense of being useful and functional to the achievement of the objectives that support the struggle both tactically and strategically.

It is clear that from this point of view, the criterion by which comrades take on the responsibility, within the class situation, of the ability to move in the field of direct action, cannot be anything that looks like the Katangese Gendarmerie or like an “armed wing” type of organisation.

Everything must be focused on the political capacity of the workers’ nuclei to strike at the right moment, in the right direction, according to the pulse and degree of workers’ consciousness, against the capitalist organisation of labour and its productivist structure, against the instruments of capitalist repression.

Katangese Gendarmerie – Wikipedia

———————————————

Excerpts from the discussion document put forward by the autonomous organisms: Autonomous assemblies at Alfa Romeo and Pirelli, struggle committee at Sit Siemens

(published in Potere Operaio del Lunedi, 31st of December 1973)

Conference of workers’ committees, 16th of December 1973 in Milan

(Introduction by Potere Operaio)

Below we publish extensive excerpts from the discussion document prepared for the conference in Milan (15th of December 1913) of the autonomous organisations, proposed by the AUTONOMOUS ASSEMBLY OF ALFA ROMEO, the AUTONOMOUS ASSEMBLY OF PIRELLI, and the SIT-SIEMENS STRUGGLE COMMITTEE. The provincial conference of the committees in Milan – like the one held in Veneto at the end of October – aimed to assess the degree of homogeneity achieved by the groups operating in different social situations, to close ranks in the organisational process, and to establish a political force that is different from and external to the extra-parliamentary groups. The criticism of these groups stems from the correct observation that most of them have retreated into institutional and frontist territory: the “party of ’69” has largely ended up identifying its representatives in the network of trade union delegates, and wants to provide a political outlet for the movement that guarantees the permanence and reproduction of the mechanism of trade union struggles of recent years [which actually have become a limitation of workers’ struggles]. Hence the thousand nuances of a position that is essentially “trade union left”, hence the “new opposition” with its neo-institutional flavour.

At this point, however, the comrades of the autonomous assemblies explain this profound transformation that has taken place in the revolutionary left, with the groups’ claim to give life to a comprehensive organisational project, and they see the root of all evil in their centralised organisational form. This is where the controversy becomes nebulous, constantly confusing organisational form and political line, lumping everything together. From this confounding arises a confused discourse on “grassroots” organisation, based on the coordination of workplace experiences, in which the potential for political leadership of the workers’ committees is diluted and not used for an open battle within the movement.

The political proposals developed at the conference are more substantial. Class interests are proposed in their radically anti-institutional form: the issue on the agenda is the development of a mass initiative outside and against the union’s bargaining on the timing of restructuring. Working hours, wages, qualifications – in short, the material interests of the workers – must be at the centre of the political initiative; and this requires forms of struggle capable of directly imposing workers’ power, of directly achieving the objectives by systematically undermining the mechanism of trade union – employers negotiation. From this point of view, mass struggle and the preordained use of proletarian violence are intertwined and complementary.

The organisational proposal to set up departmental committees can provide the necessary structure for this type of issue; it can produce a real multiplication of the capacity of autonomous workers’ leadership to manage struggles. On this terrain – as clearly explained in the document – it is possible for workers’ committees to establish themselves as a reference point for a wide range of forces, to truly become an expansive form of organisation: this opportunity must not be wasted: the circle of the organisational process must not be closed quickly, in the name of a misunderstood homogenisation.

Since the conclusion of the metalworkers’ contract, we are now on the threshold of many industrial disputes, and the situation in the factories has contradictory characteristics, at least in appearance. On the one hand, the dramatic increase in the cost of living in the first half of 1973 – not compensated for by the contractual wage increase – has led many workers to take on overtime, and furthermore, the course of the current pay dispute has generated mistrust in the struggle itself. On the other hand, we are witnessing the outbreak of dozens of pockets of struggle, or at least a great many points of contention, which reveal the persistence of tension, resulting in numerous assemblies to discuss trade union platforms and effectively hindering the employers’ programmes of restructuring. Demands are constantly focused on wage issues (in the form of increases, requests for promotion to higher wage bands, allowances, etc.) and on the rejection of increased workloads and uncomfortable working conditions (the fight against fast-paced work, piecework, and harmful conditions).

The spontaneity of workers’ movements, in which the need for autonomy develops, therefore persists, but today it is much more restrained by trade union policy. In fact, with some differences between the FIM and FIOM trade unions, the union essentially moves along these lines: containment of wage demands and application of the contract, trade union discipline with regard to factory movements, inclusion of company demands in a plan of “global” demands in favour of the weaker strata, and investments in the underdeveloped south of the country. In other words, this means isolating and repressing autonomous and spontaneous struggles, perhaps with accusations of “corporatism”, with a view to continuing the policy of collaboration for the relaunch of economic development, which saw a central stage in the last collective contract. Wage pressures are channeled into the social sphere, both in the form of adjustments to family allowances, pensions, unemployment benefits, and broader reforms, and as demands for investment. In exchange for concessions in this area, capital is offered the containment of struggles and the way is opened for restructuring (‘Pirelli agreement’). With the policy of “major reforms” set aside, reformist demands are aimed at eliminating the most serious imbalances, perhaps starting with individual sectors, in order to overcome the crisis. All this is supported by the revival of the centre-left. The somewhat hasty move to include the reformist parties in the government area was precisely an attempt to achieve control of the struggles and the relaunch of development. This primarily concerns the inclusion of the PCI, without whose external support the government has no solidity and which in recent days has revised its frontist policy [of democratic alliances], with the proposal of a historic compromise with the DC. The 90-day price freeze, rather than curbing inflation (in fact it has only slowed it down), was intended to serve as a basis for asking the trade unions to freeze wages, or at least to limit their demands for increases. All this is part of the attempt to then move decisively on the issues of full utilisation of plants and machinery and further restructuring. From what we can see, this project is coming up against total worker resistance. The period of the collective contract and the period after has also significantly changed the map of the revolutionary left.

The extra-parliamentary groups

The extra-parliamentary groups, given their insufficient roots in factories and neighbourhoods, have slipped into a claim of comprehensive representativeness, dusting off a bit of Leninist theory on the party. They have retreated into a policy of organisational consolidation, attempting to build, starting from themselves, a centralised organisation (party), from which to move to build mass organisations within the movement, instead of relying on the real moments of political counter-power expressed by working class autonomy. Instead of continuing to strengthen the situations of struggle, they have shut themselves up in a political-bureaucratic organisation, with the main aim of safeguarding the survival of the organisation itself from the attacks of state power. They have set themselves on the path of opportunism, which is leading them increasingly towards a policy of disarming the movement, ending up effectively siding with reformist and trade union politics in the hope of opening up new political spaces.

Other groups, which also start from the perspective of a centralised organisation with a claim to comprehensiveness, maintain an offensive stance and move closer to the position of organised autonomy. However, we cannot recognise them as the political leadership of the movement, because we believe that at this moment in history, political leadership must be completely accountable to the masses, while developing functional models necessary for the survival of the revolutionary organisation. We also believe that the overall leadership of the revolutionary project in its political and military aspects must arise and develop from a process within the working class and its organised expressions of autonomy. In recent years, political groups have had the function of maturing many political cadres, providing organisational tools and developing certain themes of attack within the movement. Today, as vanguards capable of taking on the autonomous leadership of the movement are emerging in various sectors of the class, their historical function is dying out, leaving behind structures of conservation and ideological propaganda. Faced with this situation, the vanguards of workers’ autonomy have become increasingly aware that they are almost alone in attempting to manage the struggles autonomously, and therefore of the need to deepen their political and organisational presence in the factory and in the territory.

Political work in the factory

Starting from the document ‘Workers’ Autonomy and Organisation’ (see above – the translator), let us clarify, in the light of a year of experience, the fundamental theme of political work in the factory. (…) The control of the production process and the containment of workers’ struggles is of essential interest for capital. This control is increasingly institutionalised within collective bargaining agreements that fully respect the fundamentals of productivity and legality. Conversely, for the workers it is objectively advantageous to disrupt the production process not only in strategic terms (since a revolutionary process that did not impose a different relationship of production would be unthinkable), but also in tactical terms, since the production process is explicitly identified with daily exploitation. There is no aspect of the production process – the assembly line, piecework, incentives, harmful conditions, rhythms, minimum wages, qualifications, etc. – that does not represent a direct target for workers’ struggle: defence against the regime of production is more than a choice, it is a daily necessity.

When it comes to these fundamental aspects of the revolutionary process, the reformists have now started to compete with capital: as aspirants to co-management they propose professionalism (through formal qualification), rotation, and political reforms to complement a new rationality of work. Instead, from a working class point of view, we have to change the incentive-based employment relationships, break the divisive mechanism of qualifications, turn the restructuring process into an anti-productive one, lower productivity and workload, defend ourselves against job cuts as well as respond to our immediate needs and objectives. This will allow workers to influence production structures from within and thus to have a substantial influence on the formation of a general revolutionary consciousness that is otherwise left to pure propaganda or the magical effect of the “party”.

The struggle over wages

Greater clarity is needed on the constant factor in the workers’ struggle: wages. Faced with the heavy erosion of real wages, the demand for wage increases has taken on a general dimension within the discussions on the resumption of industrial action. The trade union and reformist attitude is one of conscious containment of wage pressures, attempting to divert them into reformist and developmental demands (typical of this is the contrast between the demands for investments in the Italian south and the demand for wage increases, in the metal workers’ pay dispute). It is clear that the revival of economic development requires a wage truce, which allows wage levels to be brought back into line with production levels, partially curbing inflation and promoting currency stabilisation. But essentially what is needed is a truce in all struggles, and therefore the workers’ demand for higher wages today is a formidable push for the resumption of struggle in every sector.

It is about deepening the divide that workers’ struggles created between work (productivity) and wages since 1969, in order to link wages closely to workers’ needs and to intensify the struggle against work demanded by capital. It is about demands for wage increases and the ability to enforce them in practice by disrupting the organisation of production. Alongside direct increases, there is the struggle to decouple wages from piecework rates, against the straight-jacket of category increments depending on seniority, for the guarantee of wages against suspensions, against dangerous work, etc. Of course, we cannot hide the fact that the tactics used by the employer to push through restructuring go far beyond the wage arena. The restructuring process includes the political attack on class composition through new criteria of professionalism / formal qualifications, the introduction of different production cycles, the intensification of control by hierarchical structures in the factory, the dismantling of factories and departments, the introduction of the third shift, and the increase in work rates. All this must find new articulations of the workers’ struggle to counter the attack.

Objectives, forms of struggle and ‘workers’ interests’

We must develop a genuine anti-productivist consciousness in which there is a clear distinction between the interests of production and capitalist profit on one side and the interests of the working class on the other. The current intertwining of the production process and direct attacks on workers’ interests in the workplace, with increased work rates, harmful conditions, etc., means that the class struggle – beyond the orderly battles between opposing sides – takes the form of a daily hand-to-hand struggle, department by department, line by line. Unfortunately, if the great battles (for example around collective contracts) are compromised from the outset by revisionist leadership, then even the daily struggle finds its direction and strategic content only with great difficulty: everything still rests on the spontaneity of the workers.

One task of organised autonomy is precisely this: to organise the struggle against the production process, which is increasingly identified with the process of exploitation. In this context of hand-to-hand combat, the possibility arises of making the objectives of the struggle coincide with its form, which could lead to a first real overcoming of the form of the collective bargaining agreements. In the daily struggle against the production process and its horrors, the concrete objective of reducing the pace of work or eliminating a particularly harmful process can be achieved immediately in the form of a struggle that consists of working more slowly – either directly or through appropriate interventions – and boycotting harmful work. The objective and the form of struggle are based on daily insubordination to the employer’s overall production apparatus, from piecework to the assembly line, the timekeeper, and the foreman. The organisational support for this ongoing struggle can only be a well-established, articulate and autonomous workers’ presence: what we have called ‘departmental’.

Departmental committees

The organisation of the process of dismantling the capitalist productive apparatus in real terms and not in propaganda terms is the content of the proposal to form departmental committees. Department committees are opposed to the current process in which political groups close themselves and their organisational ranks. In this process the fundamental content is the group itself, rather than its real impact on the struggle. In order not to be empty organisational formulas, the departmental committees must be directly linked to the objectives expressed by the workers. Modelled on the tactical needs of the whole, they must in any case establish and bring together the departmental vanguards available to lead a process of maturation of objectives and confrontation, even if they are not immediately homogeneous in terms of overall political programmes. Thus, this network of committees can become the organisational structure capable of sustaining the struggle.

Workers’ interest

Those who act autonomously on the basis of class needs are outside the rules of the game that bosses and reformists play and must therefore act on the terrain of illegality. The term “legality” is often given a restrictive meaning, considering illegality only in terms of violence. Conversely, it is by acting on the basis of workers’ interests [convenienza] that workers’ struggles are removed from the control of the legal system: an organisation that acts on the production process in antithetical terms is illegal and, as such, those in power will attempt to suppress it in the most convenient manner and at the most convenient time. The starting point must be the criterion of workers’ interests, a criterion that is placed within the field of illegality, an interest that can sometimes be pursued even through forms of direct action that enter the sphere of so-called proletarian violence. The main organisational subject of workers’ interests, which we see growing and measuring itself in the daily struggle against production relations is the workers’ autonomy, articulated in departmental committees. This is a decisive factor with respect to the attitude of the vanguards in the coming struggles. To be able to develop moments of confrontation from a mass base that make the struggle more incisive and attack the repressive apparatus of the boss, is a qualitative leap that no group has been able to achieve so far. And on this terrain of extra-legal struggle, autonomy does not delegate: the new experimental path rejects the theories of the “armed wing”. On the basis of an organisational structure that can intervene, we need to build a network of comprehensive vanguards within the movement. We have to overcome a wait-and-see attitude with regard to the development of the coming decisive points of conflict.

There is a mistrust within the movement, but also among many vanguards, in the possibility of worker autonomy providing a comprehensive alternative to trade union management and reformism when it comes to company struggles. This mistrust leads to focusing everything on the radicalisation of forms of struggle, neglecting the content. Years of experience teach us that the trade unions are able to use even the most effective forms of struggle in negotiations, if the very nature of its function is not contested, both with regard to negotiations and, above all, regarding the objectives of the struggle. Simply raising the stakes in the struggle over the wrong objectives means, rather than increasing the capacity for workers’ struggle, pushing the union and the bosses to reach quicker conclusions. Of course, we must not underestimate the capacity to respond continuously to capitalist repression, nor forget that the conflict is not limited to the struggle for concrete goals. Today, however, it is necessary to privilege the development of a comprehensive attack on union management, attempting to break its control over even a single point in terms of objectives and forms of struggle. In this context, the workplace committees take on primary importance. The role that the shop floor committees play in taking on the struggle against the structure of work (a struggle that places them on the terrain of illegality, which also includes direct intervention as a specific moment) cannot be separated from what has been said previously: that is, the workers’ interests must also be evaluated from the point of view of the workers’ subjectivity; we need to be aware of the current balance of power and the workers’ ability to act within the class struggle.

Autonomous intervention

What exactly does organised autonomous intervention consist of and what new characteristics does it take on? As we have said, the two pillars of intervention are linked to the ongoing struggle against the capitalist production process and to the choices that workers make in their interests, therefore to the non-legalistic terrain, where the only limit is linked to awareness of the balance of power. Furthermore, we have said that workers’ autonomy is organised within the class struggle, rather than using the struggle to organise itself: a statement that is obvious but has implications. Therefore, the focus for the current moment is not to build a structure at the wider city level that organises its presence in various new situations etc., but rather the need to create situations of concrete struggle among the proletarian masses and to establish an organisational foundation. In the case of factories the organisational foundation are the departmental committees. Around these committees and in their function we need collateral structures: Red Aid groups against repression, tools, propaganda organs, etc., bearing in mind the necessities that such work, which is structurally illegal, entails.

When a factory vanguard faces the problem of extending its intervention – (both in quantitative terms, i.e. new situations to connect with, tools such as the Red Aid, or the newspaper), and in qualitative terms (i.e. how to improve the levels and instruments of intervention) – then it naturally connects with political militants, even from outside the factory, who can make their contribution. The leadership of the intervention obviously remains with the factory militants, even when the leadership has trouble imposing itself, but possesses the ability to correctly interpret mass movements and give political indications based on them: only factory cadres, who have their finger on the pulse of the class situation, are capable of doing so. Any (external) militant who, through their political work in a class situation, wins the trust of the factory committee and contributes to the development of autonomy is to be considered – quite rightly – part of the class struggle. For this reason, we believe that, given the revolutionary scrutiny concerning every militant, the problem of external versus internal militants is one to be resolved in practical situations with respect to the capacities and possibilities of each individual and the common work programme. A process of “coordination and centralisation of political work” must be developed from concrete organisational situations. Rather than inflating the organisational apparatus, it will be more fruitful to camouflage it and to reduce the public visibility of the organisational connections to a minimum. This also entails the construction of a defence structure and to organise one’s own points of support within the proletarian fabric of factories and neighbourhoods, and expose oneself as little as possible to verbal, journalistic and demonstrative (in terms of symbolic protests) infantilism.

Political work in the social sphere

Groups within the organised workers’ autonomy have long been investing energy in participating in and promoting struggles in the social sphere, particularly with regard to the housing problem. The work is inspired by the following points:

I) Extend the organisational presence in factories – based on the struggle against the work regime – to the social arena, where the general problem for now is to build organised resistance in the face of the bosses’ attack on the living conditions of the proletariat: rents, prices, services.

II) The extension is achieved by concretely building grassroots organisations within the neighbourhood, composed of young people, proletarians, tenants etc., rather than forming propagandistic bodies made up of available comrades from various political groups, such as anti-fascist committees, which are otherwise useful.

III) A direct attack, therefore, on the various forms of social oppression, giving priority for now, on the basis of existing struggles, to the struggle for housing. In particular, the struggle against evictions, for the occupation of vacant houses, for the reduction of rent and utility bills. These initiatives have to establish, where possible, a constant presence in the neighbourhood aimed at making the struggle itself possible.

IV) Therefore, linking factory struggles to social struggles is one of the dominant issues. We need to start specifying what this means in practice, beyond words. Housing, defence against social robbery, is a necessity that now affects organised workers as well, and not only the “sub-proletariat and immigrants”. A significant proportion of workers in large factories where organised forms of autonomy are present now also need to fight on a wider social level. It is important to become a real point of reference in the factory for these problems – and this is not possible unless we begin to build elements of organisation in the neighbourhoods. We have to start with the struggles that exist and build networks of relationships in the social fabric.

It is clear, however, that the real link between the factory and the neighbourhood remains the organisation through departmental committees and neighbourhood committees, unified by the same logic of attack on the capitalist structures and by the same working method: the direct and responsible organisation of the proletariat.