The question of political organisation is pressing and we have to pose it precisely: how should a political organisation relate to the class movement?

In order to approach this question we have a look at the organisational efforts that existed at a peak moment of class movement, the 1970s in Italy and try to draw conclusions from that. We find a seemingly contradictory situation. The two national extraparliamentarian organisations that were formed after the upheaval of 1968/69, namely Lotta Continua and Potere Operaio, entered a deep crisis exactly at a point when the class conflict intensified in the 1970s. Both organisations were questioned from within, primarily by local autonomous organisations of workers’ committees, and in the case of Lotta Continua, also by the emerging feminist movement. These committees criticised the national political organisations in two ways: in class terms (“against the leadership of intellectuals”) and politically (e.g. regarding the shift towards electoral politics and alliances of Lotta Continua). The autonomous organisations represented the working class core of the political organisations. They were also most closely engaged in actual practical efforts, from factory struggle to housing occupations to self-reduction of energy and transport prices to militant antifascist actions. It was not surprising that their experiences started to clash with the central lines of Potere Operaio and Lotta Continua, e.g. their abstract claim of party leadership and program or the decision to enter into alliances with more moderate ‘antifascist’ forces, who, like the Communist Party PCI, would oppose and denounce autonomous workers’ activity.

The workers’ committees contributed to the dissolution of the two main national organisations of the radical left, as they had lost touch with the more radical parts of their proletarian base, but, as often noted, the ‘workers’ autonomy’ was not able to ‘solve the organisational question’ either. This doesn’t mean that they were not aware of the fact that localism or sectorial boundaries would have to be overcome and that a coordinated and centralised political body was necessary. There were several larger organisational efforts to coordinate the autonomous bodies nationally and to intensify the debate around a common strategy. With this small series we want to retrace these efforts.

This first part of the series is a translation from 2022 that sets the scene of the first larger national congress of autonomous workers’ committees in Bologna in 1973 and the relation of the autonomous committees to Potere Operaio. The upcoming second part consists of a translation of an organisational proposal put forward by the committees and workers’ assembly at Sit Siemens, Pirelli and Alfa Romeo in 1973. In terms of chronology we suggest also reading the following article on Senza Tregua, which was a project of various autonomous committees to form a national structure and common strategy around 1975. The third part will be a strategic paper by comrades from Via Volsci in Rome, written after the movement of 1977, which sketches out their perspective on organisation, dual power and revolution. The final article of the series will try to summarise these developments politically and relate them to our organisational question today.

————————-

The “area” of workers’ autonomy

The first autonomous factory organisations began to form in 1971, taking the form of assemblies, committees and collectives. Many militants who had gradually left the political groups joined these autonomous organisations. This happened either as a result of an individual choice or because the grassroots structures, in which they carried out their political activities, gradually became distant from the extra-parliamentary organisation. For example, between 1972 and 1973 in Rome, the Enel Political Committee, the Policlinico Workers’ Collective and other autonomous organisations left the group Manifesto (partly due to a critique of Manifesto’s electoral plans – the translator); in Milan, the Alfa Romeo Autonomous Assembly broke with the Lotta Continua group to oppose the latter’s claim to hegemony over its line [1]; in Porto Marghera, the Autonomous Assembly, which arose in the aftermath of the rejection of the contract by the chemical workers of Petrolchimico and Chatillon in November 1972 [2], gradually distanced itself from Potere Operaio. An article published in ‘Potere Operaio del Lunedì’ in November 1972 stated:

“Even before the contract disputes of 1972, workers’ autonomy had felt the profound unease of not being able to express, either within the groups of the revolutionary left or in the (factory) councils where trade union control was strong, the content and forms of struggle that it potentially contained. Just as the Autonomous Assembly was formed in Marghera, so too are autonomous organisations springing up in many other situations in factories, neighbourhoods, towns and schools.”

This was followed by polemical tones towards the political groups:

“For this reason, we think it is wrong to see these organised moments of autonomy as mere instruments for the mass transmission of pre-established political lines, or as instruments for the organisation of sectoral struggles that are reunified by the political position of a group. In other words, we are against those groups that believe they are the revolutionary party and that autonomous organisations should become their mass organisations [3].”

The autonomous organisations also expressed the need to find moments of organisational centralisation that would prevent the confinement of struggles to their specific sphere, that would create a link between the factory and the social sphere, that would break the isolation of the working class by involving other subjects, such as students, the unemployed and women, in the struggle.

With this intention, on the initiative of the organised groups of Rome and Naples, a conference was held in Naples on the 25th and 26th of November 1972 to discuss the question of workers’ autonomy and the problems of the South. The themes of the need for revolutionary violence and a guaranteed wage were taken up again as central objectives (articulated in the struggles against “enforced mobility and flexibilisation, dismissals, work rhythms, high rents and high bills”) around which to unify different social sectors: workers, students, migrants and the unemployed. Finally, the problem of centralisation was addressed, putting it in the following terms:

“The organisation of workers’ autonomy is achieved not through the simple coordination of multiple struggles, but through the centralisation of the autonomous vanguards around a programme they set themselves and through the choice of appropriate tools. Centralisation is an indispensable condition in the process of building a revolutionary party [4].”

Once again, the key issue was the absence of an overall workers’ organisation, characterised by a genuine revolutionary will, resulting from a process of aggregation from below of existing assemblies and autonomous committees, capable of providing individual struggles with a general political meaning. To address this problem, some autonomous bodies organised a series of joint conferences in an attempt to develop a common line and overcome the fragmentation of the various situations of conflict. The first was the “pre-conference” held in Florence on the 27th and 28th of January 1973, in preparation for the “national meeting of organised workers’ autonomy” [5] in Bologna, scheduled for the 3rd and 4th March of 1973.

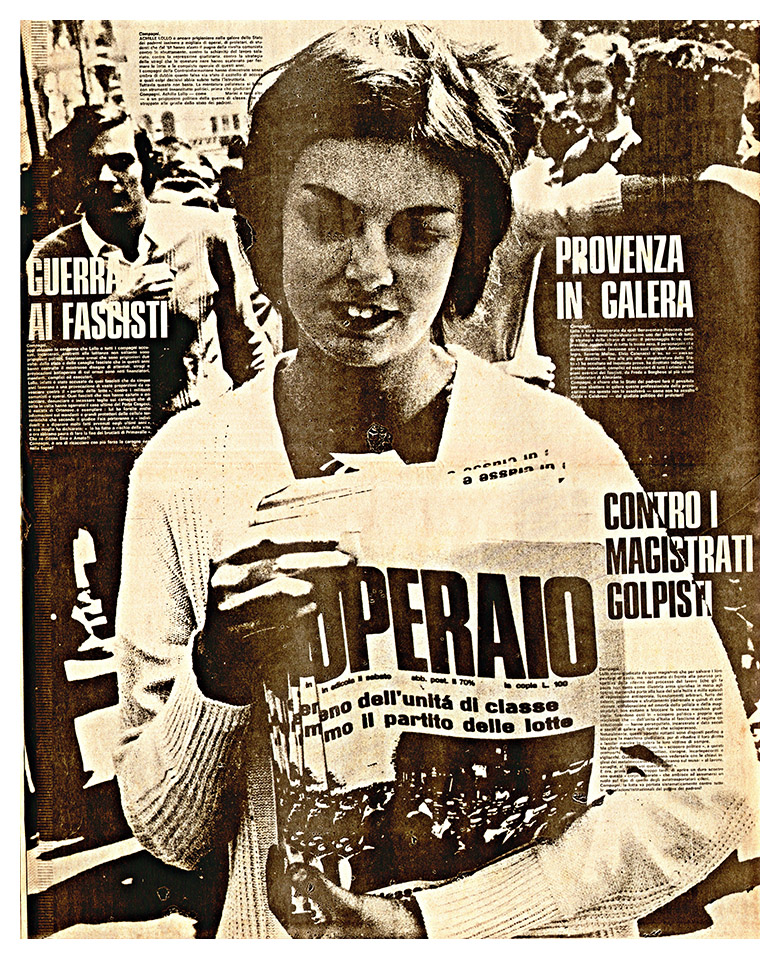

Potere Operaio gave ample space in its newspaper to the debate that took place at the Florence conference, showing curiosity and attention towards the proliferation of autonomous mass organisations, independent of the initiatives of extra-parliamentary left-wing groups and often taking positions that contrasted with, if not surpassed, those of the groups themselves.

Numerous interventions were reported in ‘Potere operaio del lunedì’ [6], and all of them highlighted the same issues, albeit in different contexts: the impossibility of resorting to trade unions in times of struggle, because they were now considered irretrievably subservient to the logic of capitalist restructuring; the need to “socialise” the conflict, i.e. to link factory struggles with those in the local area (house occupations, rent strikes, non-payment of transport), in order to unify the different proletarian categories on the basis of “material needs”; the urgency of creating a process of centralisation of the workers’ vanguards, which could give the struggles political and not just economic significance. The issues highlighted had to be resolved by overcoming the “logic of groups”, their claim to provide the line from outside [7] and the tendency to consider autonomous organisations as their own mass movement. Potere Operaio was explicitly invited to take a clearer stance:

“The problem remains, perhaps, for the comrades of Potere Operaio, who still have to decide on the long-term organisational issue of workers’ autonomy. There cannot yet be a relationship external to workers’ autonomy, but there must be interpenetration. Since its inception, Potere Operaio has been able to articulate slogans that have become part of the movement. For this reason, I believe that Potere Operaio must come to terms with the growing reality of workers’ autonomy. It must work to organise it, to build it, to make it the point of reference against the state [8].”

The attitude of the autonomous organisations towards the groups was not uniform: it included positions of decisive rejection [9], a willingness to engage in dialogue [10], and a willingness to open up and integrate. The meeting in Florence was followed by the national conference in Bologna. [11] The objectives to be pursued were set out in the conference announcement:

“What is under discussion is a project to centralise the organised forms of workers’ autonomy which – within the crisis of the system – will become the movement’s organised response to the concentrated attack by the bourgeoisie, providing a positive solution to the crisis of the groups and the sectoral nature of individual struggles and experiences.”

It also specified:

“It will not be a conference of workers’ autonomy (we do not claim the right to represent workers’ autonomy) […]. The national meeting in Bologna will have to decide on the date of a conference open to all organised autonomy (neighbourhood committees, proletarians, student-worker collectives, peasants, labourers, construction workers) and to those groups that make discussion and involvement in the programme of autonomy a long-term rather than a tactical choice [12].”

Potere Operaio was forced to confront the emergence of organisational attempts that were taking place outside the influence of the main left organisations. From an initial attitude of mistrust, it came to recognise the importance of these attempts for the future construction of the workers’ party, in light of the clear desire to overcome the limited scope of the committee in favour of a broader political organisational synthesis.

Potere Operaio appeared optimistic in feeling that the solution to the problem of the “workers” leadership’ of the movement was now close at hand, identifying it precisely in the experiences of the political committees and their attempts at aggregation:

“A political programme and an organisation capable of implementing it. This can and must lead to the overcoming of the experience of the committees and groups and their convergence and merging into a single political project and practice [13].”

Not all autonomous organisations were present at the Bologna conference. Many mass organisations were excluded. Only those groups that had already shown a shared set of objectives and a willingness to act according to a common approach, aimed at centralising the experiences of struggle, participated.

Despite initial caution, differences emerged at the meeting both on the timing of a possible national organisational process of workers’ autonomy and on the political line to be followed. Two positions emerged on the first point: on the one hand, there were the autonomous organisations of the south, particularly those in Rome and Naples, which were pushing for an accelerated organisational process; on the other, there were the autonomous organisations of Milan, which considered it necessary to proceed with a preliminary consolidation of action within their respective areas of intervention. On the second issue, the debate saw the committees in Marghera and Rome on one side

“with a political line inspired by the theses of Potere Operaio […] which starts from an assessment of the crisis of the bourgeoisie and the need to accentuate this crisis by introducing into the movement a whole series of objectives that cannot be integrated by capital, and then organising the movement to face the inevitable clash in the struggle for these objectives [14]”

on the other, the autonomous organisations of Milan, namely the assemblies of Sit-Siemens, Pirelli and Alfa Romeo, which argued that “the political line is the result of the real experiences of the working class, which the autonomous organisations interpret and guide, and not a pre-established platform”. They therefore opposed the “crystallisation of a pre-established political line that risks becoming ideology in the current situation, in which each organisation must deal with the particularities of its own situation” [15]. In the end, the debate saw the substantial affirmation of the positions supported by the organisations in Milan, with a scaling back of the organisational process and a commitment to intervene in concrete situations without first establishing a mandatory and abstract line to follow.

In Bologna, the ‘national coordination of autonomous assemblies and committees’ was established, a provisional commission tasked with dealing with mutual relations between the various organisations. The first product of this coordination was the ‘Bulletin of Autonomous Workers’ Organisations’, which was published in May 1973 and of which only two issues appeared [16].

Potere Operaio, which among its positive comments on the conference had noted the absence of the triumphalism usually present at meetings between workers’ vanguards, did not want to be excluded from what was happening. After stating that responsibility for the organisational process could not be placed solely on the autonomous committees, but rather “within the revolutionary camp as a whole”, it declared its “willingness to work together to build the workers ‘ network of work refusal, the party in the communist revolution” [17].

The internal debate within the autonomy area profoundly influenced the history of Potere Operaio. According to Judge Palombarini [19], based on witness statements given at the “7th of April” trial, the real break-up of Potere Operaio occurred after the third organisational conference in September 1971, around the issue of the formalisation of the party. Many militants, disagreeing with the position expressed by the national leadership, distanced themselves from it, continuing to carry out political activities as individuals or as part of grassroots organisations within the area of workers’ autonomy that was being organised. This satisfied the demands of those who, while wishing to create a national workers’ organisation that would unify the various local realities, did not believe in the possibility of a single group representing that moment of centralisation and saw Potere Operaio’s claim to become such a group as leading only to the progressive bureaucratisation of its structures and a loss of contact with the real situation.

Footnotes

[1] “We do not believe that the revolutionary workers” party can be formed in the traditional way: intellectuals setting a line which is then taken down to the factories to seek out the vanguards who will carry this line forward. This is not possible. The various autonomous movements must contribute directly to building the party of the working class. And we do not recognise this party in any group”. (Statement by a comrade from the Alfa Romeo Autonomous Assembly, “Potere operaio del lunedì”, no. 42, 25 February 1973, also reported in Autonomia operaia, edited by the Autonomous Workers’ Committees of Rome, Rome, Savelli, 1976, p. 25.

[2] See Marghera, oltre il bidone, Potere operaio del lunedì, no. 19, 19 November 1972, and L’Assemblea autonoma di Porto Marghera, Potere operaio del lunedì, no. 26/38, 28 January 1973.

[3] Document from the Naples conference of the 25th and 26th of November 1972, in Autonomia operaia, cit. p. 27.

[4] Communiqué from the Organising Committee of the Conference of Autonomous Committees and Assemblies, Potere operaio del lunedì, no. 43, 4 March 1973.

[5] The speeches are reported in issues 41 (18 February 1973), 42 (25 February 1973) and 43 (4 March 1973) of Potere operaio del lunedì.

[6] “Above all, the organs of workers” autonomy must be a point of convergence between the economic struggle and the political struggle: this division […] which traditionally gave rise to the trade union on the one hand and the party on the other, has been rightly criticised by a number of groups that have contributed to the birth of a revolutionary movement. But today we are witnessing the fact that these groups are reproducing this logic of dividing the economic and political spheres: they also want to promote the formation of autonomous mass organisations, but these are subordinate to the general line of the group, which claims to be the repository of the general vision” (statement by a comrade from the Sit-Siemens committee, Potere operaio del lunedì, no. 41, cit.).

[7] Statement by a comrade from the Enel committee in Rome, Potere operaio del lunedì, no. 41, cit.

[8] “As far as the groups are concerned, it must be said that, within the discourse on autonomy, the role of the groups has objectively come to an end. We must not fight them, but do them political justice” (statement by a comrade from the Workers-Students Collective of the Policlinico di Roma, “Potere operaio del lunedì”, no. 42, cit.).

[9] “The relationship with the groups must be seen solely in terms of these comrades’ willingness to actively pursue the workers’ objectives. I do not mean that the groups must in turn be at our service and do what we workers do not want to do in the factory. They must join our organisations and share their experiences with us, acting as a link between the struggle in the factory and that in the neighbourhood. The autonomous assembly does not present itself as an alternative to the union and the groups; it must present itself as a directly working-class organisation, and on this there is room for discussion with the groups and with certain factory councils” (statement by a comrade from Chatillon in Porto Marghera, “Potere operaio del lunedì”, no. 42, cit.).

[10] “For this reason, while recognising the profoundly different needs of the movement, today we cannot do without a political relationship with the organised vanguards, with the sections of organisation which, when they do not eliminate themselves by arrogating to themselves the role of the party of the class, are indispensable in the construction of what will be the workers” organisation of the communist revolution’. (statement by a comrade from the autonomous assembly of Porto Marghera,Potere operaio del lunedì, no. 42, cit.).

[11] The following autonomous organisations participated in the conference: the Autonomous Assembly of Alfa-Romeo, Pirelli, the Sit-Siemens Struggle Committee of Milan, the Autonomous Assembly of Porto Marghera, the Fiat-Rivalta Workers’ Committee of Turin, the Enel Political Committee and the Workers’ and Students’ Collective of the Policlinico of Rome, the Workers’ Committees of Florence and Bologna, the USCL (Trade Union of Struggle Committees) of Naples, the Red Leagues of the farmers of Isola Capo Rizzuto and Crotone, and the “Raniero Panzieri” Circle of Modena.

[12] Communiqué from the Organising Committee of the Conference of Autonomous Committees and Assemblies, “Potere operaio del lunedì”, no. 43, cit.

[13] Potere operaio del lunedì, no. 44, 11 March 1973. Editorial. However, Potere Operaio issued a stern warning: ‘It therefore seems essential to us that the comrades of the Committees address these issues at the conference and afterwards, not only in speeches but also in their political work. […] Otherwise, the controversy with the groups, with which some comrades of the Committees are so obsessed with, ends up being the pointing finger behind which to hide one’s own ineptitude. Because, let it be clear that in the absence of new things, the experience of some revolutionary groups remains the only fixed point from which to start in Italy”.

[14] Interview with a comrade from the Alfa autonomous assembly, ‘Potere operaio del lunedì’, no. 45, 18 March 1973.

[15] Dito

[16] The bulletin bore the signatures of the following organisations: Alfa Romeo Autonomous Assembly, Pirelli Autonomous Assembly, Sit-Siemens Struggle Committee, Fiat Workers’ Group, Porto Marghera Autonomous Assemblies, Enel Political Committee, Policlinico Workers-Students Committee, Trade Union Struggle Committees. On this subject, see Aut. Op.La storia e i documenti: da Potere operaio all’Autonomia organizzata, edited by Lucio Castellano, Rome, Savelli, 1980, p. 83.

[17] Il convegno dei comitati, ‘Potere operaio del lunedì’, no. 45, cit.

[19] G. Palombarini, op. cit., pp. 111–112.