Here in the UK you are lucky if you find mainstream media news about the current pension reform protests in France – let alone halfway decent news stories about strikes elsewhere. We’ve translated two mainstream media articles from Germany about the ongoing protests in Portugal under the ‘socialist’ government. Local comrades, please share your own impressions and thoughts!

FAZ, 19th of March 2023

By Hans-Christian Rößler, Lisbon

Anger over expensive housing and rising prices is driving more and more people in Portugal onto the streets. The average salary of about a thousand euros is barely enough to live on.

The teachers have stayed outside the school gate this morning. On the street in front of Camões High School, they raise blue flags and red posters. Some of their students watch them from the small park opposite. They have the day off because of the strike.

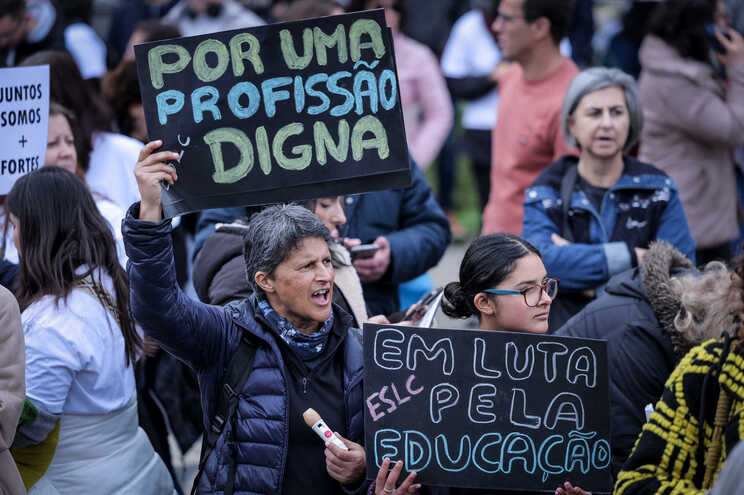

“We won’t stop”, the teachers shout, their posters read “Respect” in big letters and underneath, “No to the precariat”. Fenprof, the largest teachers’ union, has organised the small action in the centre of Lisbon with detail and care.

Industrial action has been going on since December. The teachers want the state to stop ignoring them, to finally employ them properly and offer them opportunities for promotion. They are not the only ones on strike today. Many regional and suburban trains are not running either, the railway workers are demanding more pay.

The optimistic mood has vanished

Most Portuguese people have long since lost track of who is striking. Almost all of them have already gone on strike or are threatening to do so: after the nurses, the doctors went on strike for the first time as well; before that the police, judicial officers, lorry drivers, journalists and public service workers. The first general strike took place there in November.

The consequences of the pandemic, the Ukraine war and above all inflation have led to an explosion of discontent in the country with a good ten million inhabitants, which the ‘socialist’ government has been unable to get under control for months now.

The smiles of the past years have disappeared from peoples’ faces. After the change of government in 2015, many had the feeling that things were slowly getting better again after the great financial crisis. The newly elected ‘socialist’ Prime Minister António Costa had succeeded in spreading a spirit of optimism, confidence and a little pride: unimpressed by the concerns of its European partners, Portugal successfully went its own way.

The left-wing government loosened the tight austerity corset and restructured the state finances. The country also came out of the pandemic relatively well, which had initially been hit harder than most other countries. With its successful vaccination campaign, Portugal became an international role model.

A year ago, the voters gave Costa an absolute majority. Then Russia invaded Ukraine and inflation skyrocketed – inflation in Portugal was still zero at the beginning of 2021 and by January 2022 it had shot up to 4%; then to over 10% by October 2022. Sentiments shifted. It became clear that some wounds from the past had not yet healed: the international troika had imposed painful cuts on the country a decade ago. Teachers were hit particularly hard at that time.

“Nothing has really improved,” says Emiliana Silva in front of Camões High School: “I’ve been teaching English and Portuguese for 17 years and earn 1180 euros a month.” Her salary has practically not increased in all that time, there have been no promotions. Most of her colleagues are in a similar situation. Those who have a permanent job consider themselves lucky.

“Time is for counting, not for stealing,” is a slogan the teachers use to demand that their years of service finally be reflected in their earnings again and that their work be recognised. The pent-up anger is so great that the new and smaller “Stop” teachers’ union is now pushing the Fenprof federation with more aggressive strike action. Fenprof brought more than 150,000 teachers to the streets in February for the largest demonstration since the end of the dictatorship, and 80,000 in early March.

Young teachers spend the night on campsites

Emiliana Silva was also there. Her salary is only enough because she does not live in Lisbon and commutes ninety kilometres to work in the capital. Flats in Lisbon, Porto or in holiday regions like the Algarve have become unaffordable for the middle class. In front of the school, teachers tell of young colleagues who live on campsites and in youth hostels.

Young teachers have hardly any chance to settle down. Every school year, they are often transferred hundreds of kilometres across the country. Yet Portugal needs them more urgently than ever, argue the unions. Already thousands of hours of lessons have had to be cancelled due to staff shortages, several tens of thousands of teachers will retire in the next few years. “The future of state schools is at stake. They are a pillar of our democracy,” says Emiliana Silva. Well-educated school and university graduates are the capital of the resource-poor country, agrees a striking colleague.

With an average salary of about 1,200 euros, teachers in Portugal are among the higher earners. According to a recent overview by the Ministry of Labour, 56% of workers in Portugal received less than a thousand euros a month last year. And a third of all workers only make the minimum wage, which the government increased to 760 euros at the beginning of the year; But a small flat in the big cities now costs almost just as much, leaving workers with no money left for electricity and food.

One look at the supermarkets is enough: what is on offer is as expensive as in Madrid or Frankfurt. Prices for milk, fruit and other foodstuffs have risen by 20% within a year, while rents have jumped even more: in Lisbon and Porto, the increase has been around 50% since 2017. Painfully, Portugal has remained a low-wage country despite the recent upswing. Estonia, Lithuania and Poland overtook Portugal in economic output per capita.

Many Portuguese were all the more outraged when they heard how generous the government can be when it comes to its own people. Alexandra Reis received a severance package of half a million euros when she left the board of Air Portugal. The state saved the airline with more than three billion euros, while employees’ salaries were drastically cut.

Many doctors switch to private clinics

A short time later, the former Air Portugal manager moved into the civil service and later became state secretary in the Ministry of Finance. The scandal blew up and she had to resign, as did the minister responsible. A dozen cabinet members have already resigned since the new government took office. Allegations of corruption have been made again and again.

Tania Russo has been disappointed with Prime Minister António Costa for much longer. Her eyes are small with fatigue. The night shift is still in the bones of the 41-year-old paediatrician. “Since December, six colleagues have left the hospital, most of them to private clinics.” Hundreds of doctors and nurses prefer to move to the cold north every year, to Norway, Denmark and Germany.

Tania Russo’s hospital closed the emergency room in paediatrics at night and on weekends because there are not enough doctors left. The doctors’ union FNAM sees the state health system in mortal danger in view of this “brutal bloodletting”.

“After Corona, we hoped for action, not just kind words,” says the paediatrician. The nursing staff were already on strike, followed by the medical staff for two days in the first week of March. Since Tania Russo started working as a doctor in 2012, her salary has remained almost the same, only the workload has increased.. “At the very least the government has to compensate for the 18% loss in purchasing power over the last few years. Otherwise it will be even harder to keep doctors in the public health system.” Her union is even demanding a 47% increase – because that is what judges and prosecutors received.

With a net salary of 1700 euros, medical specialists are among the top earners in Portugal. However, they do not have regular working hours. According to trade union data, doctors worked a total of eight million hours of overtime in 2022. On average, it is 300 hours per doctor, although only half of that is allowed by law. Some even work a thousand hours extra.

The state prefers to pay them more money in the short term instead of slowing down their exodus through better working conditions. Tania Russo already thought about taking up another profession. “But I feel better when I fight, especially for a health system that is there for all Portuguese,” says the doctor.

Collective bargaining has been deadlocked for weeks. The government insists that it cannot finance the demands of the doctors and teachers. Inflation nestled in at more than 8% in February. “It has practically eaten up the recent salary increase and the higher minimum wage. The extreme right and other demagogues are using the growing discontent for their own purposes,” says Sérgio Monte worriedly. He is deputy general secretary of the social-liberal trade union confederation UGT and sits in parliament for the socialist PS.

“We want wages that people can live on”

The negotiations are complicated because workers and their representatives are not pulling in the same direction: in Portugal, with its more than 200 trade unions, two umbrella organisations are competing with each other. Much larger than the UGT federation, which is close to the socialists, is the CGTP, through which the communists still exert influence; [1] they have dominated the trade union movement since the Carnation Revolution. In the last elections, the Communist Party, which had initially tolerated the socialist minority government, plummeted to just over 4%.

More and more people are organising themselves. “Vida Justa” is the name of the new platform that campaigns for a “fair life”. At the end of February, its supporters demonstrated for the first time in Lisbon. “Enough with the price increases. We want wages that people can live on,” is the most important demand. The manifesto is bilingual, in Portuguese and in Cape Verdean Creole. Among the supporters are many Portuguese who come from Africa. Their situation was already politically difficult and economically precarious before the new crisis.

“During the protests against racism and police violence, we were mostly among ourselves at our demonstrations,” says journalist and activist Paula Cardoso, whose family comes from Mozambique. Since it’s about everyday life, which has become unaffordable for everyone, new alliances are forming and more and more white Portuguese people are protesting: “There are whole families taking part, normal people, side by side with older black women. At the same time, far-right parties like Chega are growing stronger,” says Paula Cardoso. Her money often does not last until the end of the month. She has to choose whether to pay the rent or turn on the heating.

People no longer wait for the trade unions and parties. They organise themselves. “The spring of struggles has just begun,” announced the organisation “Habita”. The great housing shortage is the lowest common denominator. The government wants to quickly provide more housing and, if necessary, forcibly rent out empty flats. But there is great scepticism. “Casa para viver”, a “home to live in”, is the slogan for the next big demonstration on 1 April.

——-

Housing shortages, teacher shortages, an overburdened health system are driving people onto the streets. The social problems are increasingly coming apart at the seams – under a nominally socialist government, of all things.

By Patrick Illinger, Suedeutsche Zeitung, 19th of March 2023

“Respeito” – respect – is written on thousands of posters waved by strikers all over Portugal these days. Railway workers, administrators, nurses, doctors and above all teachers are sweeping the country with waves of strikes. They do not have much patience left for Prime Minister António Costa and his cabinet to give them the respect they demand for themselves. Under a socialist government, of all things, Portugal’s social problems are coming apart at the seams. A paradox that seems to be fuelling the anger of the workers. There were 309 strike notices in January alone, more than three times as many as the year before. On Friday, public administration workers across the country went on strike. On Saturday, the major trade union confederation, CGTP, called tens of thousands of people onto the streets of Lisbon for large rallies. “We want peace, bread and housing”, the demonstrators demanded.

(…)

An OECD report last November predicted only 1% economic growth for Portugal from 2023 to 2024. This means that for the first time in recent years, GDP growth is pushing into the orange/red danger zone for the Costa government. Even the merits of the socialists, such as the remarkable conversion to renewable energies, can no longer appease the workers.

Prime Minister António Costa, whose “Partido Socialista” has been governing with an absolute majority in parliament since last year, has been more concerned with economic growth and budget stability since he took power in 2015 – than with finding solutions to problems such as housing shortages, teacher shortages and the overburdened health system.

Liberalised markets – that was a demand on Portugal’s government in times of financial crisis, when the troika of IMF, ECB and European Commission had temporarily taken over the helm of the state. One consequence was the “golden visas” introduced in 2012, which grant non-EU citizens unlimited right of residence and thus access to the Schengen area if they purchase real estate worth at least 500,000 euros in Portugal.

The incentive brought billions of euros into the country. But the uprooting of ancestral populations was the result. Rich Chinese, Brazilians, South Africans and Russians bought real estate. Historic blocks of houses were luxuriously renovated. The old town of Lisbon, not so long ago the living space of lower and middle-class families, has turned into a jungle of Airbnb flats. But the flow of money into Portugal has created hardly any jobs.

Isabel Camarinha, General Secretary of the CGTP, observes a “very deep dissatisfaction and great indignation” not only in individual occupational groups, but among workers and the general population as a whole. The most recently negotiated 5% wage increases are not cushioning inflation-related losses. Only now, more than seven years after taking office, Prime Minister Costa wants to abolish the questionable “Golden Visa” lure. For a long time, economic metrics, KPIs and indicators were seen as more important to the ‘socialist’ government than the real living conditions of many sections of the working class in the country.

—–

[1] Unlike in the UK, in many European countries trade union federations were attached to particular political parties or currents