A comrade of ours wrote this report for friends from Kon-Flikt, a collective in Bulgaria.

Attacks on the working class continue

Since Kon-Flikt published (August 18th, 2022) our previous article, the threats facing workers in Britain have become even more stark. Although the infighting in the governing Conservative Party has increased the level of unpredictability it is clear that a new phase of “austerity” (hardship for the working class) is planned for the coming months and years.

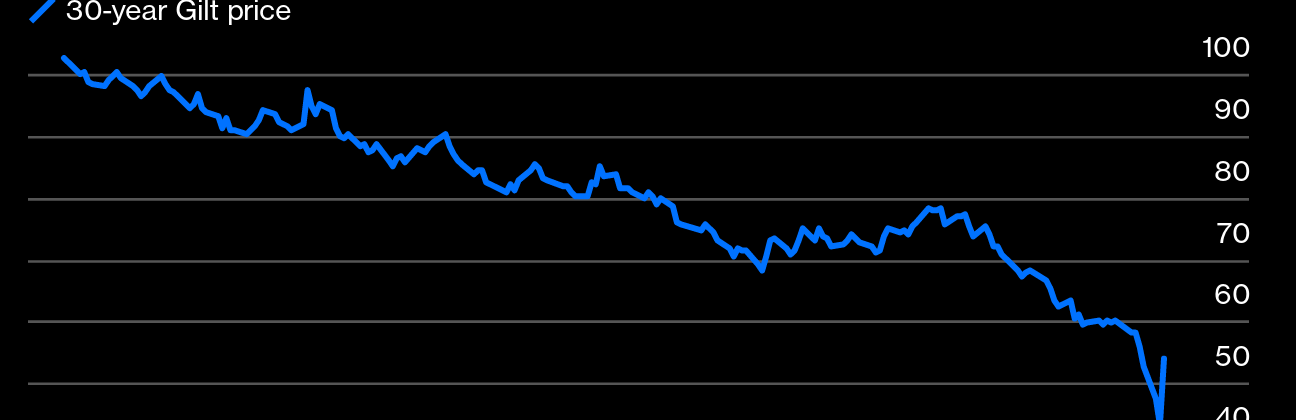

The current Finance Minister is pushing forward towards a programme aimed at, in his words “eye wateringly hard decisions” – hard for workers, welcome for the capitalists. The immediate aim for the Government is to regain the confidence of the financiers by finding enough cuts to massively reduce a £72 billion (approx 82 Billion Euros) gap between state income and expenditure.

That new round of state-organised attacks on workers living standards is a further addition to the difficulties piled on us that we mentioned in the previous article. The current official rate of annual inflation remains over 10% while food prices have increased by 14% during the last 12 months. It seems almost certain that the next increase in welfare benefits will be below the rate of inflation – a cut in their real value.

The price of gas and electricity has risen so sharply that the Government issued financial support to cap the price for an “average Household” to £2,500 per year – that figure had approximately doubled over 12 months. Originally the state-funded support available to avoid even more unaffordable bills was to last for two years. One of the first effects of the move to austerity is a decision to end the scheme after 6 months, at the end of March, 2023.

In the face of the growing resistance that we describe below, there have also been moves to strengthen the state’s repressive powers. The government has already suggested adding to the existing widespread legal restrictions around strikes. One idea that they have published is to increase even further the levels of participation required for a strike vote to be legally recognised.

The government also made its intentions clear in July when it changed the law in a way that “removed restrictions in previous trade union laws which prevented businesses from supplying temporary agency workers to cover employees who are taking part in strikes”. Further legislation being proposed would mean that legally-recognised transport strikes must agree to running some services otherwise workers can be sacked and Trade Unions can be sued by the employers. The nature of that particular restriction echoes an infamous legal ruling around a rail strike in Taff Vale, South Wales – 120 years ago!

The moves towards repression and a strong state do not end with more legal restrictions around organising and striking around work. Mass protests and actions involving elements of direct action have continued to appear on the streets, only interrupted by the bizarrely surreal period of “national mourning” following the death of the Queen. These protests have often been in response to the heightening ecological disasters with new direct action focussed groups such as “Just Stop Oil” (https://juststopoil.org/) emerging. The continuing evolution of activities beyond the restrictive control of the state compliant organisations have frequently involved disrupting traffic or other “spectacular” activities. The ruling class reaction to this has provided momentum for the increasingly “right-populist” governments to strengthen their law-based social controls.

There were isolated examples of the new move to restrictive policing when individuals were arrested for publicly expressing anti-monarchical views either by shouting slogans or questions or displaying placards.

Earlier, the first attempt to strengthen the law against protestors was the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act that was passed in April this year. This had been opposed by many mass demonstrations under the slogan “Kill the Bill” and some of the worst measures were kicked out during the process in Parliament. However a new Public Order Bill is working its way through Parliament. A legal journal summarises the measures – “The Public Order Bill re-introduces the criminal offence of locking on to other people, objects or buildings; introduces a new criminal offence of obstructing major transport works and ‘key national infrastructure’, including airports, railways, printing presses, and oil and gas infrastructure; extends stop-and-search powers for police to search for and seize articles suspected to be used for protest-related offences; and brings back the concept of serious disruption prevention orders.” The authors of the article, from the “International Bar Association – “the global voice of the legal profession”, helpfully include a quote – Mark Stephens, Co-Chair of the IBA’s Human Rights Institute, says ‘It’s difficult to see how this Bill is compliant with basic human rights standards.’

Working class resistance

Since June there has been ongoing struggles by significant sections of the working class both to defend wage levels and to fight back against other attacks outside the workplace.

The wave of strikes under the control and direction of the mainstream Trade Unions have continued within the legal restrictions imposed by the state and complied with by the Union leaders.

The most prominent series of rolling strike actions across Great Britain has involved railway workers. That struggle started in June and are ongoing. Three further two day strikes are planned for early November with further ballots also scheduled to allow strikes to continue into 2023.

Postal delivery workers have also started a series of 19 day long strike actions planned to run from October to December.

As we wrote earlier this year, we are seeing layers of workers taking strike action for the first time. An example of a strike on a site with no recent history of militancy was in the Port at Felixstowe (on the East coast of England), also later joined by Port workers at Liverpool (in the North West of England). A series of week long strikes have significantly impacted supply chains and the movement of foods and other products.

Overall, it remains to be seen how many of these prolonged pay struggles. will result in an adequate wage increase this year or early next year.

Although the current and future strikes in the public sector have been well publicised there have also been struggles in the manufacturing sector.

In July workers for the Cadbury’s chocolate manufacturers, part of the multi-national Mondelez combine, accepted a deal which their Trade Union “Unite” congratulated themselves on with the headline “Unite secures up to 17.5% pay boost for 1,000 Cadbury workers”. Such a deal would indeed have been a genuine victory – a deal probably above the ongoing inflation. Unfortunately, even reading Unite’s own description the deal is far less of a victory. Their own press release makes clear that the 17.5% includes bonuses rather than an increase on the basic pay rate. Far more significantly, the deal is for two years, meaning that there is a very strong possibility of it being overtaken by inflation. Nevertheless, that settlement is better than many others that are being proposed, or even accepted.

It appears that Cadbury’s is not unique amongst food processing corporations where profiteering allows room for local demands to be raised. A current issue of a Trade magazine, “Food manufacture” carries material from two Trade Unions, Unite and GMB, detailing ongoing or imminent strike action for higher pay.. These included a strike in Bakkavor, a food processing factory in Lincolnshire (Eastern England), where an initial strike by 700 workers is planned for 9 days at the start of November. The demand is for “a rise that reflects rising living costs” after the workers rejected a 6.5% offer. The articles also details scheduled actions in 3 other food and drink production and/or distribution companies where the Unions are negotiating for rises of around 9.2%, the official inflation rate earlier this year.

During the summer wildcat strikes broke out on the offshore rigs in the North Sea where drilling for oil and gas takes place. The Trade Union “Unite” seems now to have regained control of the situation but workers overwhelmingly rejected a 5% pay offer. Three further 2 day strikes are now planned between early November and the middle of December.

Just as the Trade Unions asserted their control over the North Sea strikes, in general the activities over the summer have been marked by the Trade Unions keeping their grip over the strikes, shackling them within legal boundaries and blocking any potential for effective spreading of actions or coordination across boundaries. The tempo of the process is still dictated in the framework acknowledged by the state, employers and Trade Unions. Many strikes such as those on the railways have become bogged down in prolonged “wars of attrition” while other sectors including health workers and teachers.are still imprisoned in the debilitating pre-strike legal processes.

In all the above, and many other, cases it remains to be seen what the future holds. As yet, there have been very few, if any, genuinely above-inflation settlements. In the absence of any “index linking” or inflation triggered supplements, workers’ militancy will be stretched to the limit if they need to get on an annual merrygoround of chasing pay increases to keep up with price rises.

More positively, there have also been concrete examples of action and solidarity spreading outside the national territory. In March, Rotterdam dockers took action in support of ferry workers sacked by P&O. At the time of writing, deepening effective links with workers involved in the wave of strikes in France would be an important boost to the class’s struggle on both sides of “La Manche”.

Beyond the struggle for wages

In addition to the previously mentioned direct action protests around environmental issues the summer has also seen the start of an organised resistance around the cost of electricity and gas – the main fuels for both heating homes and cooking.

The campaign “Don’t Pay UK” (DP) has established itself around three demands – the limit on prices to be lowered to the level before April 2021, an end to users being forced to accept the significantly more expensive pre-payment meters and emergency tariffs to prevent unnecessary suffering and deaths during the coming winter.

To achieve their targets DP originally planned to gather together 1,000,000 signatories committed to refuse to pay energy bills when that “critical mass” has been achieved. Following the government’s decision to only keep the price pegged for 6 months the campaign is likely to start to encourage supporters to immediately cancel their payments or take other action in solidarity with the over 2 million households who are already in debt around their electricity bills.

Signs of the counter offensive

We have already mentioned the efforts to increase the powers of the police and the courts around both strike and protest actions. There are other indications that the employers are beginning to push back to defend their positions.

A school in Romford seems likely to have been the first use of the new law allowing workers to be brought in to break a strike. That move would not be possible, for example on the railways, where skills, training and sometimes recognised certification are required. On the other hand, the precedent has now been set for breaking the strikes of workers in situations where they can be replaced by outside workers with only a minimum of training or preparation.

Another area where the employers are counter attacking is in the Royal Mail, the postal delivery company, part of “International Distribution Services”. Early in October, following the start of the rolling series of strikes, Royal Mail threatened to cut up to 10,000 jobs during 2023.

One result of the Trade Union controlled disputes becoming a series of actions being turned on and off and stretching over many months is that there is a real possibility of workers becoming demoralised. That process is not inevitable if workers break through the compartmentalisation and legal restrictions that the Unions are happy to work with. Until that happens the big employers, particularly in the public sector “services” may well be content to allow protracted controlled actions that allows them to cut their short-term wage expenditure while looking for exhaustion and disillusion to set in.

One tactic adopted by the reformist left is to deliberately move the focus away from activities that can be open to working class self organisation and shift it towards the illusions of electoralism. That tactic will probably ebb and flow in the next period as the next UK General Election could take place as late as January, 2025 although a date in 2023 or 2024 is probably more likely.

At the time of writing the state-compliant forces around the Labour Party and Trade Union leaderships are using the degree of chaos in the ruling Conservative Party to bellow for a General Election. This is a long standing strategy adopted by the left. It is a key move towards diverting their followers’ energies down a path entirely safe and familiar to the ruling class’s order. For example in the Don’t Pay UK campaign an argument appeared that “the immediate task is to force a general election”. In response to the calling of a demonstration on November 5th calling for “General Election Now” the proposal was that “all DPUK energies should, for now, go into making that a huge protest”. Or, in other words, instead of working with those unable to pay bills we should go marching through London to listen to a stream of leftist windbags telling us how an election will solve our problems.

The next phase

In Great Britain, the attacks on the conditions of life for the working class are the severest certainly since the massive restructuring of the 1980s and quite possibly since the conditions during the global slump of the 1930s. Looking at the increasing and widespread need for workers to use charitable food banks and the unaffordability of housing and heating there is a strong case to say that our day to day struggle for survival has features closer to the 1930s than the 1980s.

.

As elsewhere in this world wide crisis of the profit-based system, we can expect the working class resistance to continue as the class that owns and controls continually seeks to shift the burden further onto the class of producers. The conscious aims of most of those in struggle has started off with a limited vision. It is not too much to imagine or demand the essentials of life that the ruling class continue to enjoy – being able to feed, clothe and nurture their families, knowing that adequate health care is available when needed, heating their homes without falling into debt, breathing air that isn’t poisonous, care and support for all in need,having healthy recreation available for all and secure and nurturing educational and social facilities for our children.

It is in the course of those initially defensive struggles that there is the potential for workers to again uncover the possibilities of reconstituting society. When struggles become generalised, overflowing the artificial divisions both within workplaces and between workers in struggle inside and outside workplaces, then workers start to glimpse the shape of a new world – one that allows for a sustainable satisfaction of needs based on the cooperation of “freely associated” producers.

Ned Ludd

October 2022

——————–

Previous report from June 2022

Workers in Britain – Start of a fightback?

This article deals with the current situation and touches on the past, present and future of class struggle in Britain. It is worth restating that the working class in Britain is an intrinsic part of the global working class – a class that crosses all the ruling class borders. This is, of course, not an abstract issue. The world economy has created countless connections around production and distribution that link workers’ lives across every continent. It is in that spirit of proletarian solidarity that this article has been sent from workers in Britain as a contribution to our comrades around Kon-Flikt.

Same as everywhere – workers expected to pay the costs of crisis

Workers in “Great” Britain [1], or more simply Britain, have seen their wages and social benefits forced downwards over many years. Wages were forced down further than in many other “major economies” during the early years after the 2008-9 crash [2]. Currently the real attack on workers living standards is shown by analysis which earlier this year showed the biggest drop in pay levels for 9 years [3]. By June, it was the biggest drop for more than 20 years [4].

For those dependent on state benefits the position is possibly even worse. In April of this year the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (a long standing and respected charity analysing poverty) published a report whose main heading was “Main out-of-work benefit sees its biggest drop in value in fifty years” [5].

The ruling class has been able to make these attacks despite often appearing confused and incompetent. The political “establishment” stumbled into a referendum in 2016 as a means of dealing with, and supposedly defusing, threats to the unity and power of the governing right-wing Conservative Party. The result (known as Brexit), to leave the European Union overturned 50 years of the British ruling class’s political and economic strategy. The decision has created an upsurge in separatist tendencies, particularly in Scotland, and significantly threatened the delicate political arrangements that holds together the two elements of the “United Kingdom” [6].

The resulting mess has also created supply chain problems and reduced the capitalists’ access to relatively cheap labour from the EU. Brexit (implemented in the most disruptive way to pacify a “populist” layer in the Conservative Party) has exacerbated the effects of the global crisis in Britain and has been another element where the costs have been paid by the working class.

A summer of workplace struggles?

The term “Summer of discontent” [7] is being used to describe an expected wave of strikes that are being forecast across many sectors in Britain. The words echo the description “Winter of Discontent” [8] used during the winter of 1978-9. At that time many workers, particularly employed by local Councils, took widespread and effective strike action. Those actions defied wage restraints that had been enforced by the Labour Party Government, working with the Trade Unions, following the acceptance of a loan from the International Monetary Fund.

In 2022 the most obvious factor pushing workers towards action is the sharp and constantly accelerating rise in prices of necessities including rent, fuel for vehicles, electricity and gas for heating and cooking at home, food and other necessities such as sanitary products. This follows years where wages for many workers have already fallen. There is now a recognition amongst many workers that the situation must be changed and that taking action to increase wages is necessary and has a chance of succeeding. The belief that gains can be made is also helped by the fact that employers in many sectors have admitted that that they now need to employ more workers to successfully make profits.

The British ruling class and its government has blamed at least part of the latest wave of price rises on supply disruptions resulting from the war in Ukraine. There may be some truth that the disruptions have reduced supplies and increased costs but trying to lay the blame in that direction has not dissuaded significant sections of the working class from acting in their own interests. This highlights the contradictions and unevenness in “class consciousness” in that simultaneous with this escalating willingness to take action the majority of workers appear to have a degree of sympathy with their bosses’ “war aims” in Ukraine – a military victory for Ukraine using finance, personnel, weaponry, logistics and intelligence provided by NATO, which includes UK. Millions for the military, hardship for the workers! has never been more appropriate.

The wave has started

The first week of strikes that involved rail workers across the whole of Britain started on 20th June. The strike reduced the rail services to nothing in many areas and to a bare minimum in the remainder. The strike was called about pay but also about the threat of job losses and erosion of pensions [9]. At this stage, the employers and the Rail, Maritime and Transport Union (RMT) are clearly both looking to avoid further strikes. In the words of Mick Lynch, the RMT General Secretary, ” We’re not ruling out strikes but we have not put down any dates for any strike action… We are not going to name dates [for further strikes] immediately and we’re going to continue working constructively with the companies to strike a deal”[10].

There is already a long list of workers in mainstream Trade Unions who are in the process of preparing for strike action in the next few months. These include workers at Heathrow – the biggest London Airport, doctors and other Health Workers, teachers and Post Office workers. Slightly bizarrely, barristers, a higher grade of lawyers in the legal system, have already taken national strike action.

The official Union machines are already showing their intent to keep the strikes controlled and compartmentalised by refusing to connect strikes across sectors. Here, they are happy to comply with the legal framework imposed by the state. The law imposes stringent conditions on the process of balloting that must take place before a Trade Union can legally call a strike. In addition, a Trade Union in Britain cannot legally involve its members in strikes of solidarity with other workers.

The media have paid a lot of attention to the more prominent actual and planned disputes where the traditional Trade Unions will, at least at first, exercise control keeping actions separated, controlled and safely in the boundaries of all the legal restrictions.

That traditional model has been the case, for example, with a whole series of strikes in different localities by bus workers working for the company Arriva. Those strikes have been organised in each of the localities with the Trade Union “Unite” agreeing a deal with Arriva that the isolated strikers have then accepted [11]. That strategy is starting to crack as workers are seeing both big price rises for necessities and the admission that labour shortages are appearing. At the time of writing, Unite and Arriva have been unable to stitch up a deal acceptable to drivers striking in West Yorkshire, in the North of England.

“The precarious economy” – grassroots organising and base unions

Unsurprisingly, there has been less publicity from the capitalist media about actions outside the safe state framework mediated by the mainstream Trade Unions.

In May, workers on 16 oil and gas rigs in the North Sea (off the coast of Scotland and Northern England) took wildcat strike action [12]. The action was quickly suppressed by the Trade Unions working closely with the employers to end the self-organised struggle.

In recent years there have been a series of grass roots driven actions in the “gig” economy – the arena of “precarious” employment with irregular hours and conditions and often with “self-employed” status which eliminates many statutory rights. On occasions these have been self-organised such as that by couriers working for “Deliveroo” in Liverpool [13].

There have also been many actions amongst sections that have not traditionally been organised, such as cleaners in London. These have often involved action by migrant workers and have seen the emergence of “base unions” such as Industrial Workers of Great Britain (IWGB) and United Voices of the World (UVW). Another participant in that “milieu” is the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) which, in Britain, combines its anarcho-syndicalist tradition with being a Trade Union legally registered with the British state in accordance with the full legal framework.

An interesting current example which perhaps also reflects the new confidence and combativity is can be found here. That article refers to a struggle by workers in a bar in Brighton on the English south coast. In the article there is also a reference to the tensions between the mainstream unions and the newer base unions as they compete to benefit from workers who are relatively new to Trade Unionism. The view of IWGB on one of those conflicts can be found here. The workforce in question are the couriers for Deliveroo whose drivers self-organised outside the Unions in the dispute from Liverpool reported at [13]. An academic but informative analysis of struggles around Deliveroo can be found here.

Where could this lead?

It is impossible to guarantee any forecast about the course or outcome of these developments.

Almost certainly many workers will experience strike action for the first time. That, in itself, will provide some of the new generation of the working class with experience of or even sharper insights into the “real movement” of our class.

As the process rolls forward it is unforeseeable how many of the experiences will be positive and how many negative.

There will certainly be many challenges. We have already touched on the role of the Trade Unions in seeking to defend and increase their own role – riding on the back of workers anger and frustration, channelling it into safe channels where mediation can take place and fundamental issues of social control and class relationships remain hidden. Workers wanting to generalise their strikes (breaking sectoral boundaries or linking with those struggling on social issues and defence of working class interests beyond the workplace) will inevitably have to confront the union/capitalists/state imposed boundaries.

That issue of bottom-up generalisation is markedly different from the Left’s cheerleaders for Trade Unionism and their calls for a General Strike, under the control of the Trade Union bureaucracies who retain all the tools of top-down direction and compliance with the system of exploitation.

We can also anticipate issues that arose during the last phase of large scale wage militancy in Britain. During the late 1960s and 1970s sections of workers struggled , often successfully, to temporarily defend the level of wages, reduce differentials particularly those around gender and sometimes race and improve working conditions. However, that experience also showed that there is no automatic link between those struggles and any move to challenge and overturn the domination of capital in all its manifestations.

More specifically, workers will also be confronted by the challenge of successfully defending their living standards in a period of inflation. Repeated one off strikes is a recipe for disillusion and demoralisation. On the other hand, there will be no end of siren voices seeking to direct workers towards state-centred solutions.

It is tempting to be over-optimistic about the result of the expected strike wave, imagining a new widespread awareness that workers witness and understand “The Birth of Our Power” [14]. In reality we have no way of knowing whether concrete gains around wages, living standards or working conditions, even temporary and partial, will be won.

A different and crucial benefit would be the emergence of clusters of militants imbued with an understanding of the need for working class community, solidarity and self-organisation. The strengthening of that layer will in turn increase the capacity of the whole class and all those experiencing oppression to carry forward their own struggles in future waves. No matter how this summer develops we need it to be the start not the end of renewed and increasingly conscious struggles.

Footnotes

[1] Great Britain is one major island together with smaller offshore islands (not Ireland). It comprises England (the biggest population with a heavy concentration around London and the South East; Scotland in the whole of the North of the island and Wales in part of the west). Prior to the economic restructuring starting in the 1970s all three had areas of solid working class communities based around traditional industries such as coal, iron and steel extraction and processing, ship building, heavy manufacturing and labour intensive sea ports. 50 years of restructuring has totally reshaped the economic basis of those working class centres in all three of the “sub-national” areas.

Simultaneously with that transformation the state has generated new bureaucratic arrangements, both elected and unelected, in Scotland and Wales. That process, along with increasing alienation and deprivation, has interacted with a growing movement for national separation, particularly in Scotland.

[2] https://cep.lse.ac.uk/pubs/download/cp422.pdf – 2008-14

[3] https://inews.co.uk/inews-lifestyle/money/cost-of-living-uk-workers-pay-drop-growth-match-inflation-1569956 biggest pay drop for 9 years

[4] https://www.theguardian.com/money/2022/jun/14/uk-pay-falling-inflation-energy-bills-unemployment for more than 20 years

[5] https://www.jrf.org.uk/press/main-out-work-benefit-sees-its-biggest-drop-value-fifty-years

[6] The “United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland” was created 100 years ago following the partition of Ireland when the British bourgeoisie agreed to an independent capitalist state to come into being in the present Republic of Ireland. From the late 1960s until the late 1990s there were continuing episodes of barbaric violence in Northern Ireland around its position in the Union. A US brokered deal created a tense but longstanding “normalisation” (of exploitation) which is now threatened by the “Brexit” decision.

The UK government and the EU agreed on arrangements that left Northern Ireland attached to the EU for customs and trade purposes to avoid creating a visible border between the two jurisdictions on the island. The UK government is now seeking to pacify the Democratic Unionist Party In Northern Ireland and factions in the Conservative Party by unilaterally reneging on the deal. There is more analysis and background in https://www.angryworkers.org/2021/09/04/workers-in-northern-ireland/

[7] https://www.npr.org/2022/06/24/1107244513/in-addition-to-the-rail-strike-britain-braces-for-strikes-in-other-industries gives a brief media presentation

[8] Taken from a quote in a play by William Shakespeare

[9] Occupational pensions linked to contributions made during work with employers in both the public and private sector is a significant part of the income of many retired workers.The income from that source often supplements the basic state pension to a degree that the pensioner is not entitled to various other benefits such as the “State Pension Credit”.

[10] https://www.nationalworld.com/news/uk/when-is-the-next-train-strike-in-2022-what-rmt-boss-mick-lynch-said-about-more-rail-strikes-this-year-3746303

[11] The Trotskyist site www.wsws.org has plenty of useful coverage about this

[12] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-tyne-61511426

[13] https://www.leftcom.org/en/articles/2019-12-02/the-self-organised-struggle-of-liverpool-couriers-highlights-the-difficulties-of

[14] The title of a semi-autobiographical novel by the revolutionary Victor Serge describing the historic wave of struggle during the period 1917-19.