Reflections on 50 years of political experience

As AngryWorkers we are grappling with the question of how organisation relates to class struggle in a meaningful way. We line out some basic ideas in our new book ‘Class Power on Zero-Hours’.

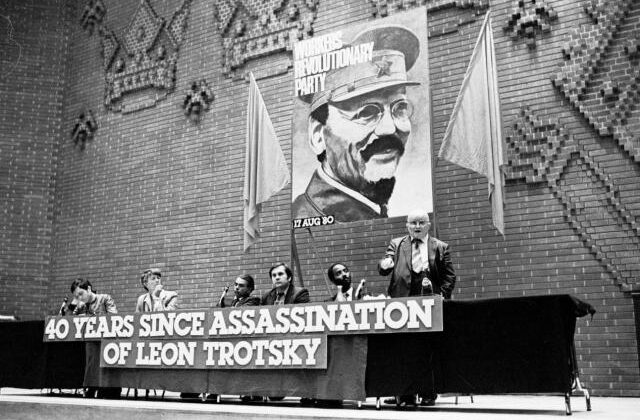

During a series of open discussion meetings in London we had the pleasure of meeting and learning from older comrades, most of whom are former members of the Trotskyite ‘Workers Revolutionary Party’. We knew about the pretty awful inner-dynamics and questionable politics of this organisation. When we met the comrades we were initially surprised about the fact that these were the most kind, open minded, sharp and dedicated people we had come across in a long time. Which raises the question even more acutely of how an organisation that speaks in the name of ‘emancipation’ could turn commitment, intellectual curiosity and spirit against its own goal and the people involved. The following reflections of one of the comrades are beautiful and valuable inspirations in our search for ‘being organised together’.

I grew up in South London with left of centre parents. My mother went on the Aldermaston (ban the bomb marches) and as a young teenager I started going on anti-apartheid marches, CND marches etc and joined the Labour Party Young Socialists and went out canvassing for the labour party in the 1964 general election which saw Harold Wilson end years of Tory government. But I soon got bored with the Young Socialists and disillusioned with the Labour Government’s tacit support for the US’s war in Vietnam.

I went on the big anti-Vietnam war march that ended with the riot outside the US embassy in Grosvenor Square in London and was very pissed off when the next march didn’t end in an even bigger riot as the march leaders (Tariq Ali and co), led the march away from the embassy

By this time my brother had joined the Socialist Labour League ( forerunner of the Workers Revolutionary Party, WRP ) and under his influence I started to go to their meetings. Rather than the overwhelmingly middle class make-up of the Labour Party young socialists the SLL was mostly working class.

The SLL/WRP was part of the Fourth International founded before the second world war by Leon Trotsky, one of the very few leaders of the Russian Revolution still alive in the 1930s after all the others had been executed by Stalin. The Fourth International was founded to fight against the Communist Parties (CP) that were part of the Third International and now totally under the control of the Russian anti-working class dictatorship.

This fight against Stalinism dominated our activities and the necessity of this was made clear to me in my first experience of trade union activity. I was working on building sites and had become the union convenor on a very large site in Wandsworth – the Arndale shopping complex and council housing tower blocks.

We had already had a fight on the site to block non -union (Lump ) labour. At this time the builders union was led by the right wing and they undermined our efforts by issuing union cards to the subcontractor employer for all his lump workers.

Now a national building workers strike started for a wage claim but the union worked hard to prevent it becoming and all out national strike, instead calling out individual sites for short periods of time. Building workers became more and more frustrated by this and were calling for all out strike. In many areas rank and file workers started ‘flying pickets’ where striking workers would go to sites that were working and stop them. The union disowned this kind of action and I watched at first hand as the Communist Party (CP), which was very influential in the rank and file of the union, provide a kind of left cover for the union leaders, urging people to wait and abide by union instructions.

Eventually the strike was lost and months afterwards the state cracked down on a group of the flying pickets in the north west and jailed some of them for conspiracy, including Des Warren who then left the CP and joined the WRP (see his book -The Key to my cell)

But while Des Warren and other building workers had been seriously trying to spread the strike, which I also did on my own site by ringing the union everyday demanding that our site come out which we had voted to do, my political work as directed by the SLL was really just a propaganda war against the union leaders and the CP and as I will go on to show this was always the way with my industrial union activities.

In the early seventies with the Tory government trying to bring in laws against the trade unions ( Labour tried to do the same) there was a widespread radicalisation of the working class. Gerry Healy, the man who had led the SLL since the 1950s, declared that we were entering a revolutionary period and that it was necessary to convert the League into a revolutionary party. This was to be done by mass recruitment and by converting our twice weekly paper into a daily paper.

And this began to happen. We were able to set up new branches all over the country and at a large conference the Workers Revolutionary Party was launched.

At the height of its influence in the mid 70’s the WRP had about 150 full time staff working as journalists, typesetters, printers, distribution staff (producing a daily paper, a weekly youth paper and books), staff in bookshops, finance office, security, and full time organisers around the country. It also had affiliated groups in a number of countries round the world. For a year I was one of the full time organisers.

Despite all these resources, with hindsight, we organised nothing of any lasting value in the working class. Instead the organisation became a madhouse.

Not long after the WRP was launched with growing recruitment and growing sales of its newspaper, a general election returned a labour government and for many people in the working class there was a mood of ‘problem solved’. Our membership began to dwindle and paper sales began to decline but none of this could be honestly reported and considered.

Inside the party there was a sect like mentality in which honest open discussion was impossible. People only repeated what the leader said and he said that we were in a revolutionary period and that anyone who said otherwise was a petty bourgeois coward.

So at all meetings people reported that their membership and paper sales were going up. No-one dared speak the truth and then be ridiculed in front of other members. All conferences and meetings took the same form – Gerry Healy would make the opening report on the growing revolutionary situation and then everyone else would try to repeat what he had said, all trying to be more ‘revolutionary’ than the others. Then there would be a unanimous vote.

So we ended up in a lunatic kind of life. The party revolved around finance – so every member had to pay subscriptions and every paper ordered had to be paid for even if they weren’t sold, so when a branch secretary reported increased membership and increased paper sales those had to be paid for each week. Where to get the money? The only way to get it was not to go out selling the paper in the evening but instead go and see wealthy middle class sympathisers and convince them to give a large donation. So now even less papers were sold and so it went on. Bundles of papers were collected by the branches each day and often were not even opened.

At the same time on the international scene far from fighting bourgeois nationalism as we professed Healy began to align himself with all kinds of people – Robert Mugabe in Zimbabwe, Colonel Gaddafi in Libya, Assad in Syria, Saddam Hussain in Iraq, Yasser Arafat in Palestine, the Ayatollahs in Iran – all of them people who in the 21st century the masses rose up against, but we were singing their praises and of course behind the arguments made by our party that these people were anti-imperialists was the reality that Gerry Healy was getting money from them, often for printing work that our presses did for them.

In 1985 the WRP exploded when Gerry Healy, was expelled for the sexual abuse of young women comrades. (for a first hand inside look at this whole story read Claire Cowan’s book ‘My search for revolution and how we brought down an abusive leader’)

The WRP was one of many many groups around the world that had their origins in the Fourth International founded by Leon Trotsky.

I think that what I am writing about the WRP applies in one degree or another to ALL of these groups – for example in the UK, to the Socialist Workers Party, The Militant, Socialist Action, Socialist Outlook, Workers Power, etc etc etc.

For all of them building their own party/group was the main focus of all their activities.

The Fourth International was founded upon a theoretical basis that can be summed up as follows:

The 1917 Russian Revolution was the opening shot of an age of wars and revolutions. The success of the revolution in Russia and of its leadership – the Bolshevik party – opened up the road for revolution around the world. This didn’t happen because there were no Bolshevik type parties in other countries, only reformists and indecisive lefts. Then the counter revolution, led by Stalin, imprisoned the Russian working class, and through his control of the Communist Parties of the Third International prevented the working class world wide from following in Russia’s footsteps. Uprisings in China, Spain and elsewhere were defeated largely because of Stalin’s directions for the Cps to support the ‘democratic’ bourgeoisie. Stalin had needed to murder all the Russian revolutionaries to consolidate his power and feared his fragile grip on power would be threatened by working class victories anywhere else.

In 1938 Trotsky founded the Fourth International (FI) to fight against Stalin.

So for Trotsky the masses globally were ready for revolution and only held back by treacherous leaders, both Stalinist and reformist. This outlook was summed up in his remark that ‘the crisis of humanity is reduced to the crisis of working class leadership’.

Ie, the only barrier to world revolution was the subjective factor, the outlook of working class leaders. So the task for the Fourth International was to gather together all the working class militants who agreed with its platform. It would fight to take control of the working class from the Stalinists and reformists. Progress was marked by the growth of the FI.

This perspective had a certain validity in the 1920s and 30’s but after the 2nd world war the world was very different..

Trotsky’s analysis had no room for any consideration of the merits of Bolshevism, made no room for any discussion on the actual experience in the Russian Revolution ( for example to what extent did the Russian working class ever have any say or control over events), and made no room for a real analysis of the development of capital once it had seen off the revolutionary global upsurge after the first world war and even more so after WW2..

Far from opening up the age of war and revolutions the Russian revolution was followed by the period of the greatest ever expansion of capital into all the parts of the world which had previously been outside its realm. This, and the defeats of the 30’s, had a profound impact on the working class, on its organisations and its outlooks. Yes, the working class grew to cover the entire planet but at the same time in many counties reformism ‘worked’. Capital responded to ‘Workers of the World Unite, you have nothing to loose but your chains’, by beginning mass production of cheap commodities. Henry Ford started to produce cars for the workers. Large sections of working class became ever more atomised and commodity obsessed. The organisations of the working class became ever more incorporated into the social control mechanism and bureaucratised. But for us none of this was rooted in the actual development of capitalism, it was all the product of treacherous leaders who had to be exposed and replaced – by us.

(I don’t want you to think this is an adequate description of what went on in the 20th century, only to bring home how the perspective ‘that the crisis of humanity is the crisis of working class leadership’ stopped any thought/activity about the actual fighting ability of the working class itself – simply that it had to be led differently.)

Now the FI split and split and split – seemingly over great theoretical issues, but in reality over control by this or that white male leader. Every sect has a leader who hates anyone challenging his control, outside voices must not be listened too, real debate is stifled. So what did organising in these groups look like. Basically everything was centred around building the party/group because this was all that was needed to overcome ‘the crisis of leadership’.

At the heart of this, for the WRP, was the paper which everyone went out to sell. My day – and most members – would go like this. Get up at 5.30am, pick up newspapers, go and deliver them to all our daily subscribers in my area, sell the paper outside a workplace as the morning shift went in, go to work, sell the paper in work, after work sell the paper round the council estates and talk to people who had been taking the paper regularly, then sell round the pubs and at the end of the evening meet up with other comrades in the branch to hand over money.

Through the paper contacts were established. Further discussions/public meetings etc would lead to people becoming members and they in turn would become papers sellers, delivers and money raisers. This was in the ‘good period’ before the decline in membership and sales.

When ever there was activity in the working class, ie a strike, a social campaign and so on, the paper would report on this and in turn sellers would take the paper to the scene, always looking for recruits. This was really a kind of fishing exercise. Any upsurge of the class opened up opportunities – not for the working class, but for us to recruit members and paper sales. This kind of recruitment actually tended to ‘disorganise’ the class. If a militant steward in a factory joined us then increasingly his or her attentions would be turned away from organising in the working class to building the party. Many workers joined the WRP and then left precisely because of this contradiction.

Also when there was a spontaneous movement we (and all the groups) would vie to ‘lead’(control) it, and in reality, kill it.

On occasions, where there were issues simmering in the working class but not addressed by the trade union or labour leader, we would launch our own initiatives. For example during the Thatchers years of high unemployment we launched ‘Right to Work’ marches across the country. After the jailing of the Shrewsbury building workers for conspiracy we organised a march to demand their release and we did the same again after the miners strike to demand the release of all the miners in jail.

But these actions had as their objective the spreading of our influence. (Another example of this was the SWP’s Anti Nazi League which was launched by them when there was a big upsurge of anti-racist activity, but despite the Anti-Nazi League gaining wide support, the SWP leaders shut it down because for many of its members this work became more important than building the party so it had to be stopped.)

Never, anywhere, was there any sustained, centrally organised work to build up the fighting strength of the working class itself – since that was not what was needed, just the removal of rotten leaders who held the class back. And of course each of the FI groups knew that it was their group and their group alone that had the necessary ideas to replace this rotten leadership.

There was work done by individual members in their workplaces.

For example I left the building sites and trained as a sheet metal worker and ended up as a shop steward in the British Aircraft Company (later British Aerospace) main factory in Surrey. I was there when the government jailed some London dockers for secondary picketing in their fight against containerisation and casualisation of the docks. On news of their jailing we called a stewards meeting and voted to call a mass meeting after lunch to recommend all-out strike in support of the dockers. But the same thing was happening across the country and by the afternoon the government let the dockers out of prison.

Not long after the whole aircraft industry had a wage claim in. Management refused to budge. From the shop stewards we recommended a strike. The mass meeting (5000 on day shift, 1000 on nights) narrowly turned it down and instead asked that we go back and carry on negotiating for 2 weeks. We did but still no offer. Now during this period one of the smaller factories in Gloucestershire staged a 24hour sit in. When we went back to our mass meeting with nothing to offer clearly the shop floor had been talking about things and someone from the floor proposed an occupation. This was carried and at once it was clear that lots of people had thought about what to do and without any instructions hundreds of people rushed to occupy the main office buildings where another 4000 office staff ran the air industry’s head quarters. The management, who have spies on the shop floor, were also prepared and had the building guarded by hundreds of security men with dogs but the workers outwitted them and shut down the entire headquarters, closing production across the country – (we were working on Concorde, other civilian planes and military planes and missiles). The wage claim was won in full but I was sacked on made up charges of violence against a manager and the right wing and CP stewards worked successfully to stop any strike for my reinstatement.

So I was blacklisted and only got another job because the unions at Rolls Royce Motors were so strong that the employers could only hire union nominees so whenever there was a vacancy a blacklisted member got a job. This militancy at Rolls was very much in evidence. We struck for two days a week for several months for a national engineering wage claim that would not even benefit us because we earned way over the national rates.

Then when the Labour Government brought in a wage freeze we went on all-out strike for higher pay. This brought us into collision with the government but also with the unions who were supporting Labour and yet we stayed out for three months. I worked hard to unite our strike with the firemen who were also on strike but eventually, under continuous pressure from the unions, our men voted to go back to work with only minor concessions. Not long after Rolls shut its London factory.

Then I worked in an artificial limb factory. This was highly skilled, highly paid work and the minute I and a few other Rolls workers started there we knew the end was on the cards. The company had developed a new kind of artificial limb which could be made by people with 16 weeks training – not the 5 years that most people had in the factory. But the week I started was the beginning of the miners strike and I campaigned in the factory and amongst London metal workers to go out on solidarity strike but all the time the union was fighting against this saying if we did then we would be bankrupted by the new laws which forbade solidarity strikes and that Scargill and the NUM didn’t want solidarity strike but instead wanted everyone to pay into the miners strike fund.

After the miners were defeated our management provoked a strike by demanding people work overtime. And then shut the factory down as they had already set up facilities for making the new type of limbs in the Philippines.

Now all this work that I, and many other comrades, did in the factories was really disconnected with our party work. The party only measured things in terms of recruitment and paper sales, and so all of these industrial experiences almost never got really honestly discussed. With hindsight what I took as growing revolutionary militancy was nothing of the sort, it was just the efforts of the working class to keep what it had achieved in the post war period of welfarism and full employment` and to a certain extent a class war truce. The militancy was there but it masked an ever growing narrowness of working class outlook, sectional and politically tied to reformism. When Thatcher tore up the ‘truce’ the militancy went down like ninepins. The miners and print workers fought alone and the industrial militancy was replaced with the gig economy.

But back to the WRP’s ‘party building’. The uselessness of this approach came to a head with the 1984 miners’ strike. Here was the greatest class battle in the UK since the second world war, very much signalling the end of the post war welfarism that most industrialised countries had lived under. Not a single left group played any useful role in helping the working class challenge and to some extent go beyond the boundaries imposed by the union leaders – including Scargill.

The WRP went into the strike with many miners in our ranks. At the end of the strike only a few remained as members. They had voted with their feet because for them organising the strike, winning the strike was number one, whereas we wanted them to build the party amongst miners. The WRP refused to allow its members to participate in the miners support groups and instead we would go to all the marches and rallies to sell papers that called for a general strike, but this was just wordy propaganda, we never did anything to seriously advance such a call.

The end of the miners strike and our irrelevance to it, and the collapse of the Soviet Union were the background to the WRP breaking up in 1985. When accusations of the sexual abuse by Healy surfaced I think they were listened to by the members because the party’s world view was being undermined by reality. Healy had always previously been able to expel or silence any one who raised criticisms of him.

The party split -some defending Healy – the majority voting to expel him but then the majority soon going in many different ways.

I could go on all day with details of how not to organise but it would become tedious. In short we thought the road to revolution lay in building the ‘vanguard’ party and by definition we were the vanguard party. The idea that it was necessary to assist the working class build up its own fighting capacity never entered our heads until long after the party broke up.

And of course all of the vanguard parties know the ‘answer’. Marx’s comment that the educators themselves have to be educated found no echo.

Some more positive experiences after the break up of the WRP.

The expulsion of Gerry Healy did not immediately lead to a change in outlook. Initially it was seen as a case of get rid of the bad apple and then carry on as before. But the genie was out of the bottle with most of us still dominated by all the dogma of the FI. But people began to ask the question how could a ‘healthy’ revolutionary movement have such a person in its leadership. This then opened up, for some people, a search for ideas, for new forms of activity that has gone on ever since. Only a few people though, most of the members could not live with out the old certainties and looked around for other ‘parties’ or just dropped out of politics.

So from 1985 onwards I and others have been on a non stop political journey. Looking back I almost shudder at how many years it took to break with all kinds of dogma, above all the idea of the vanguard party. Many people and events have helped shape my subsequent thinking but just to mention 3 significant things.

Meeting up with a group of Iranian exiles in London. They came from different political groups in Iran but now in London were being forced to question how had the Ayatollahs come to power in the revolutionary upsurge which overthrew the Shah. Amongst other things they wrote that they had misunderstood the nature of the working class ‘vanguard’. They all thought it was formed by those who had read Marx, Lenin etc and wanted to dedicate their lives to revolution. Now they saw that the vanguard can only be the best fighting elements of the working class itself, gaining their authority through the struggles of the class. This simple statement, now so seemingly obvious, came as a revelation to me and others.

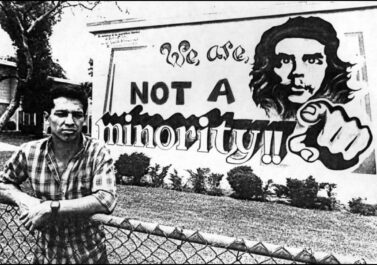

The next thing was my time spent in South Africa. I first went during the last years of the apartheid system having developed links with NUMSA, the metal workers union there. Now at this time I was still in my party building mindset but there I was working alongside people who had actually organised the working class. Working in conditions of illegality and repression they had built up union organisations that in a short space of time had millions of members. They also built up community organisations in every aspect of life. We would talk for hours about how this had been done. And these were not simply ‘trade unionists’, they were revolutionaries, highly critical of the ANC and their vision of post apartheid democratic capitalism. They wanted not just the overthrow of apartheid but of capitalism too.

With my outlook, apart from bringing them masses of banned books by Marx etc, I contributed little to their struggle. I could explain about the role of the South African Communist Party in propping up the ANC but I didn’t really have anything useful to add to their efforts to stop the take over of their powerful, politically independent unions, by the ANC. Over a 3 year period the ANC, assisted by the reformist trade unions of the USA and Europe and the communist parties slowly got control of the unions and made them into its subordinate partner, and it was only when this was done, when the working class had been got back under control, that the regime could let Mandela put of prison.

But working with these people, real organisers of the working class, had a great impact on me.

The final break from my ‘build the party’ outlook came with the war in Yugoslavia. One of our comrades was a Serb working in Paris. He wrote to us about the mining region of Tuzla in Bosnia where the multi-ethnic industrial/mining communities were surrounded by ethnic cleansing armies trying to force them, through starvation, into ethnic division.

This was a region whose militant class outlook was founded in a famous miners uprising of 1920 when hundreds of miners from different neighbouring countries who worked in Bosnia’s mines took part alongside Bosnian miners in an armed uprising. Though the uprising was crushed this international and multi-ethnic struggle laid the basis for it becoming the biggest resistance held territory within the Nazi empire and then again the biggest enclave of resistance to ethnic cleansing in 1993. It was the region of Yugoslavia with the highest rate of interethnic marriages and the highest number of people simply describing themselves in the census as ‘Yugoslavs’, rather than a particular ethnicity.

Our Serbian friend pointed out that the Bosnian miners had given one days pay a month to British miners during the 84 strike, couldn’t the British unions now do something in return? We held a meeting of some interested people in London and decided that at the same time as passing this message on to the UK trade unions we would organise our own convoy of food even though none of us had any experience of anything like this.

The response to this proposal was astonishing. All over the country we were able to speak to large meetings of people from all walks of life, eager to help collect food, volunteering to go on the convoy, going out to collect money and so on.

Our proposal had touched a raw nerve. Everyone was watching this appalling war on tele but felt unable to do anything, now they could.

We were never a charity. We always said ‘if you want to feed hungry people there are plenty in the UK’. From the start this was an initiative to try to rekindle working class organisation of international solidarity.

Over the next three years we took maybe a hundred lorries of food, educational and medical supplies and mining equipment to Tuzla, hundreds of people came with the lorries into the war zone, stayed with people there, saw for themselves the realities. And we also brought people out with us, teachers, miners, health workers who came to tour Europe and explain to people what was going on, that it was a lie that people from the different ethnic groups had woken up one morning, wanting to kill each other.

While this frenzied activity was going on my ‘party’ building outlook was being stretched to breaking point. I remember going to a meeting of my own political group which by this time was called Movement for Socialism, and one man saying ‘well all this convoy stuff is very good but how many people have we recruited.’ Not long after that as one of the convoys was parked by the side of the road in Bosnia trying to negotiate our way through hostile front lines, with fifty or so people, ex squaddies, young unemployed people, some Muslims, political activists, a delegation of postmen from Liverpool, other trade unionists from Spain, France and the UK, with our Bosnian translator, I thought to myself here was something more of a ‘party’, or rather, a more useful organisation than anything that had called itself ‘The Party’. It was not for these people to have to go and ‘join’ anything – it was for revolutionaries to join them.

In the UK we consistently tried to involve the trade unions in the campaign and at the level of the membership we got great support but the unions as organisations (with a few exceptions) they did nothing and countered our efforts by telling their members to support War on Want – a charity to feed hungry people.

So now the idea that had been growing amongst some of us fully took hold. Instead of building the self proclaimed Revolutionary Party, we had to work to rebuild real working class organisation and in particular international organisation.

The experience of organising the convoys and associated campaign gave a little glimmer of what could be done. Tuzla was never defeated and it was no accident that a few years ago it was the scene of massive demonstrations and riots against poverty and the corruption of all the political parties and the EU. In the midst of the riots people tried to set up a workers council.

I’m still on a political journey trying to understand and overcome many years of blinkered existence and trying to make sense of a now rapidly exploding world. I’ve heard many ex-WRP members say, well despite what the Party became under Gerry Healy it did teach me many things, especially in terms of reading Marx. I dispute this. You didn’t have to be in the WRP to read Marx or to learn to print or any of the other ‘skills’. Yes we read Marx and much else but always this ‘theory’ was then tailored to meet the needs of a guru led sect. I think all of this time in the WRP only began to become useful with the overthrow of Healy. This was the beginning of our liberation. It was followed a few years later by some of us voting to wind up our version of the party. This freeing of ourselves from the straitjacket of old dogma allowed work to begin to think about what Marx had actually written, not what all the later self appointed custodians had interpreted it to mean. To think about how to make real Marx’s assertion that the liberation of the working class is the task of the working class itself – not a passive working class led by ‘marxists’. This means looking for the opportunities to allow working class self organisation to be strengthened, to be widened in outlook, to be maintained over time. To fight within this self-organised movement for an understanding that only with the end of capital’s rule can any lasting solutions be found. And finally to be totally flexible in what we think of as working class organisation – not to confine our sights simply to the work place but to extend it to every facet of life. The growing barbarity of capital’s rule is going to force/provoke people to act in relation to climate, to population movements/refugees, to social break down in every sense. I remember talking to a group of young activists in Durban and asking how they came into politics. ‘Through chess’, they replied. Apartheid made everything political. The corona virus is giving us a vision of this on a global scale.