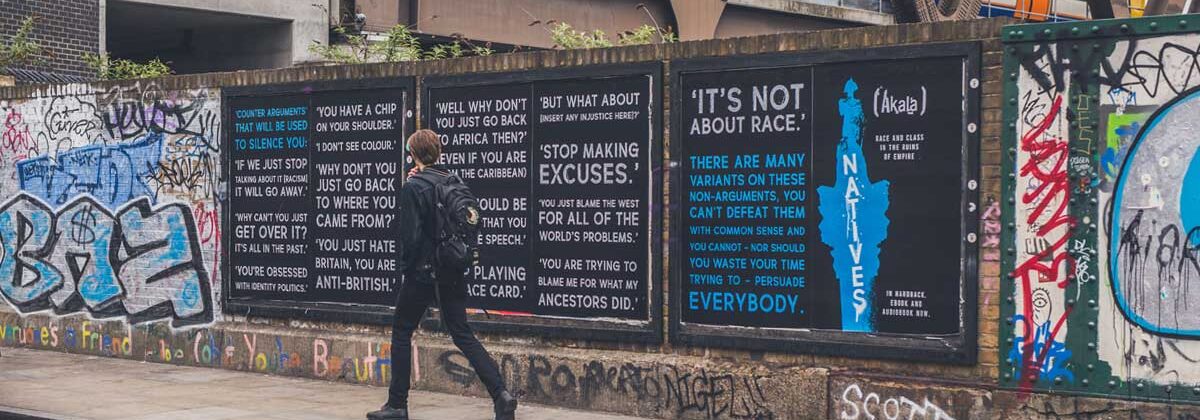

Akala has become the go-to, articulate, media-savvy commentator of race relations in the UK. He has formulated his thoughts into a concise and readable book on the topic, which has had mainstream crossover appeal. The main questions he tackles are: why and how racism, specifically against black people, has existed historically; and how it operates today. One might suppose he includes some possible answers of what can be done about it, but this is decidedly lacking given his pessimistic conclusions. I think in large part this lack of viable strategy or political proposals is the product of his analysis, that while broad-ranging and pertinent in many regards, is ultimately trapped in a framework of ‘black exceptionalism’ that focuses too much on the realm of culture and ideas as a driver of change, rather than material bases.

So, while he talks about class at various points throughout the book, and admits that there is much crossover between assumptions based on race and class indicators, there always seems to be an insistence that black boys come off worst in every situation. In other words, it is primarily the racial marker that is the emphasis of continued disadvantage and negative stereotyping, rather than one’s class position in society. While this race-centric view is easier to maintain when pointing out that black males are disproportionately affected by police violence, it becomes difficult to uphold when speaking about the reasons why black kids are the majority victims and perpetrators of gang-related violence. In order to defend themselves against racist accusations that crime is ‘a black problem’, even proponents of race-centric views like Akala have to play the class card and point out that it used to be ‘white’ Glasgow which had the highest street murder rate. This is never spoken about as white-on-white crime. Instead, it is fairly obvious that high crime rates are related to poverty and the informal economy.

‘Black exceptionalism’ is problematic in a number of ways: it limits the possibilities to build a wider working class movement that sees similarities as the basis for a united front (e.g the worst educational attainers are white working class boys, which implies that while the form of disadvantage might differ if you are black, the class marker is maybe more of a pertinent indicator for how the teachers and the school system treats you); it leads to a politics of anti-racism that doesn’t challenge the existence of class hierarchies as the basis for how society is organised (e.g. it focuses on poverty as an issue of lack of equality, rather than a systemic outcome of capitalist exploitation); and it fails to interrogate the class divisions and different positions people occupy within the black ‘community’.

The notion of a ‘black community’ should be interrogated more too. Akala is a self-proclaimed pan-Africanist, which has a chequered history in relation to Marxism, emphasising as it does the unification and shared experiences of a people from African descent around the world, rather than on an international proletariat. Akala himself defines his role as a pan-Africanist to cultivate a ‘mutual understanding between the populations of Africa and its various diasporas – given that we face similar and connected historical challenges…’ While he guards against a view of a black monolithic experience, it is tricky to not fall into the obvious pitfalls such an outlook engenders. Namely, that black people all over the world have more in common with each other than their peers of different races. He is largely able to get away with putting forward the notion of a ‘common black experience’ because of the fact that black people in the UK are overwhelmingly ‘working class’, and also make up only 3% of the UK population. But it is still a bit lazy. In other countries with majority black populations, the usual class stratas prevail which undermine the notion of a simple black unity or common experience. And in the USA, where the black population is nearly four times the population of Greece, it seems absurd to think that their racial identity marks out their common and unified social position, political sympathies and life experiences.

To get around this this problem, the common denominator Akala draws on to bring such a varied and disparate race together is their shared experience of ‘white supremacy’. Akala talks about ‘white supremacy’ being built on imperialism and continuing nowadays through institutional racism mainly within the education system and policing, for which he does a good job at recounting his own experiences and wider psychological effects (e.g. internalisation of racist ideas) of these repeated and detrimental encounters. He acknowledges the limitations of this approach when he says, “it’s understandably hard to convince our Igbo homies that fled Biafra or those that fled the war in Sierra Leone that mighty whitey is the sole – or even in many cases the primary-issue.” His conclusion is that approaches and dialogues have to become more subtle and nuanced. But while this pluralism might be effective at explaining particular instances of injustice, will it help to identify and explain what are essentially the changing class dynamics and tendencies that cut across all regions and peoples?

While a theory of race that centres on anti-imperialism (and what Akala extended by Akalas to white supremacy) sheds light on why we are here (‘because you were there’) and the social position black people were entering when they came to the UK (i.e. to do the shitty jobs), it fails to explain other things. For example: how racism operates between non-white groups e.g. Indian peoples’ racism towards black people; why black people originally from the Caribbean have been less materially successful than Indians who came to the UK at the same time or even Africans more recently; why white working class boys continue to be the worst educational attainers.

Obviously, the history of colonialism and national liberation struggles is important to understand the experiences from which people came from, and which contributed to black people’s own understanding of their situation in 70s Britain. However, the role of class within such struggles is often understated. In anti-imperialist struggles in the ex-empire, the role of the national bourgeoisie is obscured in the efforts to kick out the white enemy, and it it is this emphasis on whiteness and white superiority as the driving force for colonial expansion that is a problematic focus of Akala’s analysis. Yes, there was an intellectual system that tried to justify racial hierarchies and the dehumanisation of black people, a scientific racism, but this ideology did not exist for itself or as an inherent and preceding ‘anti-blackness’. Rather it was useful to justify the drive for capitalist expansion and sought to maintain the supposed naturalness of the social order and divisions within the working class. Here we talk about the ‘white man’s burden’ to impose a colonial system of slavery and resource plunder as a backbone of industrialisation. Akala argues that this mythology around the dichotomy of black = bad, white = good has a long-standing history that went back to the cursed sons of Ham in the Bible (posthumously) and having its roots in European history and culture, as well as in the Middle East and North Africa before that. However, an ideology of anti-blackness cannot be divorced from the context in which it was developed, namely in a system of hierarchies and oppression that already existed. So to name ‘anti-blackness’ as the reason for the particularly persistent racism suffered by black people ends up being tautological.

Another problem arises when he tries to differentiate between black and white nationalism, tracing their different genealogies and aims to posit that black nationalism = good, white nationalism = bad. This is dangerous territory and he ends up reproducing the binary ideas that separates black from white with badness and goodness. He ends up aggrandising some famous black nationalists to make his point, like Bob Marley and Muhammed Ali rather than others like Idi Amin and Robert Mugabe. He also simplifies the stark political differences within the ‘black community’, e.g. by not mentioning Muhammed Ali’s break with Malcolm X once the latter moved away from Islamic Black nationalism towards Marxism, which finally cost Malcolm his life. Even earlier on, in campaigns such as the one for the Scotsborro Boys (black boys accused of rape and threatened with the death penalty in the 1930s), political differences between black liberals of the NAACP and black communists were vicious – expressing the significant class divisions within the ‘black community’ even in the times of Jim Crow. Akala’s race analysis lends itself to these kinds of generalisations and in the process, wipes out the very ‘nuance and subtlety’ he advocates later in the book. Any revolutionary class politics needs to challenge nationalism, regardless of whether the people making the call are an oppressed minority or not.

At various times Akala does point to the limits of ‘anti-blackness’ as the main driver of racism throughout the book. In his account of slavery as a historical phenomena that pre-dated slavery from Africa to the USA, he talks about the fact that black people were often a minority within the slave population e.g. in southern Spain. He also says that black slavery in the Americas was not inevitable. The fierceness of the process of dehumanisation of black slaves in particular at this time, he says, was a result of the ideology that developed that questioned their very humanity. While all slaves up until then were seen as inferior, and anyone in fact from the lower orders were treated badly, Akala maintains a black exceptionalism. He pinpoints the development of a ‘scientific’ racism that cemented black slaves as the lowest of the low, as sub-human, marking their treatment out as the worst there has ever been. While he thinks capitalist greed does not fully explain why black slaves were treated the absolute worst, he emphasises that systemic racism could not exist before the ‘technological gap’ between Africa and Europe became a chasm. This process of capitalist development can be interpreted either as ‘white imperialism’, or alternatively, the normal workings of a capitalist system that is becoming more global, intense and dependent on the under-development of other regions. We would say that the latter is a clearer analysis of historical developments. This is not just about a semantic difference but has implications for the political imperatives to overcome oppression and racism and building a new society.

The gaps in the class analysis become even clearer when Akala talks about certain contradictions that develop amongst oppressed people when they climb up the class ladder. So for example, he writes of Toussaint L’Ouverture of the Haitian revolution: “…the charismatic and militarily brilliant leader of the Haitian revolution was at one time himself a slave owner. He instituted a draconian labour regime when he was governor of Haiti, had his own adopted ‘nephew’ executed for being too unkind to French ‘planters’ – slave owners – and even snitched to the British about a slave revolt brewing in Jamaica, of which the suspected instigators were hanged.” How does Akala explain this turn of events? He says, “Humans are complex.” “Human imperfections and contradictions” however, is a shallow analysis for what happens when people gain power and develop different class interests. He writes:

“…from a pan-Africanist perspective, how will successful ‘black Westerners’ react to this changing world? Will we maintain emotional links with the interests of the global south beyond a generation or two or will we fall into the trap of the ‘black bourgeoisie’ that black American writer Franklin Frazier famously lamented way back in 1957? Will relative comfort and privilege change us for the worse?”

The question is, why wouldn’t black people be changed for the worse?! Unless you think there is some spiritual reason that accounts for their intrinsically higher moral standing, this quote shows how Akala’s assumptions of a superiority based on shared experiences of oppression close off the possibility that they are subject to the same class forces as everyone else.

He makes a similar mis-step when he talks about African elites – both as business partners with the British in their roles as middle-men in the slave trade, and now, as bankers or politicians of whatever. Their “greed and caprice” is simply put down to “human flaws”, which themselves are the result of “complex phenomenon”. ‘Human flaws’ cannot simply account for these changing dynamics of class struggle and relations, and and it is this glaring omission in the analysis where Akala ultimately falls down.

Akala is openly pessimistic about where to go from here, seeing black people in the UK permanently joining the white underclass, trapped by history and racism in its institutional forms now. An analysis that errs more on the side of ‘race stratifed by class’ rather than class as the basis upon which racism can be used and reproduced will inevitably end up in a bit of a political cul-de-sac.

Akala’s thoughts on critical whiteness though, are interesting. His point is that notions of racial inferiority and superiority affect the oppressors as much as the victims, more so in fact, because the oppressor’s sense of identity is built on shakier foundations, in other words it is built on the negation of the other. It is also interesting to link the changes in capitalist development and who the next global superpowers will be with the increasing insecurity of ‘whiteness’ and what this actually means in different geopolitical landscapes. However, it is odd that when he refutes the claim by some in the far-right of an era of ‘white genocide’ he says that,

“In America, people racialised as white, whether they become a minority or not, will still hold virtually all the key levers of economic, military and political power.”

This is an odd point to make, and also misleading. Many black people occupy powerful positions of governance in the USA, with black-majority councils, black mayors etc. Why, under a situation of changing demographics would white people automatically continue to dominate? And which white people are we actually talking about? Certainly not one of the millions that make up the white underclass in America…

He does a good job of explaining the longer historical legacy of slavery and colonial relations to explain the roots of racism. The question of course is, how is racism experienced in modern Britain, what forms does it take, and why does it continue to persist, despite the end of colonialism, slavery, and state-sanctioned segregation like Jim Crow in the USA, and the development of formal equality legislation that makes it illegal to discriminate against someone on the basis of their skin? To answer these questions, Akala recounts his personal experiences of racism as a window into how institutional racism operates currently and in the recent past (particularly throughout his childhood in the 80s and 90s but also of his parents and grandparent’s’ generation). This focuses particularly on school and education as a driving force of the reproduction of racism, and policing, which targets young black mean as the main perpetrators of crime.

Overall, Natives is worth reading. But its dearth of political proposals signals a lack of a deeper class analysis that would be necessary to really understand how racism is reproduced and what then can be done to undermine and struggle against it. How will pan-Africanism help us when inequality between the rich and the poor is widening and more and more sections of the population become disenfranchised? How does pan-Africanism or anti-imperialism not end up apologising for the oppression and exploitation organised by the post-colonial or post-apartheid states?

Akala might be right that the black population in the UK is predominantly working class – but we shouldn’t fall into the trap of simplifying a complex social group. There are black high-ranking managers, media people, academics, political middle-men, religious leaders, cops. There are neoliberals, socialists and christian-fundamentalists. Racism against working class black people is infused with a disdain towards the lower-classes – racism itself has a clear class stratification and doesn’t necessarily create a unifying experience. If we look at concrete cases of working class organising within segments where black workers are over-represented (from council tower blocks, minimum wage jobs to prisons), we would insist that a unified class approach does more to undermine racism than politics of ‘black exceptionalism’. The class has to unify from below – and unifying means that differences between workers in terms of ethnic backgrounds, language, migration status, sex are not treated as identities, but as issues that pose additional organisational challenges on the path of protracted struggle against exploitation and oppression.