We translated this editorial of the current issue of Kosmoprolet, a magazine by comrades from Germany. On the current moment…

Since the pandemic took firm grip on the world, viral horror has become normality. What made everyday life bearable before the plague has since fallen victim to the imperative of distance. The horizon of the vaccination campaigns is just a return to familiar dreariness. The rapid development of the vaccines needed for this is an expression of a gigantic advance in the productive forces, which is, however, constantly undermined by the way knowledge about natural processes is applied under the standards imposed by profit and national interests. While there is hope in the metropolises that the infection can be brought under control after another winter of considerable mortality, the situation for national economies with a subordinate position in the world market looks bleak: in the scramble for profits and vaccines, the marginalised are largely on their own in the face of the rapidly advancing contagion. Only a modest number of state leaders have come to realise that even from the egoistic perspective of the highly developed national economies this is fatal.

As much as there is to learn from the virologists now promoted to pop star-status, they remain classic theorists of compartmentalised knowledge: although they know about the influence of global warming, agribusiness, population concentration, and air traffic on epidemiological development, for them the economic driving forces remain completely unclear. Thus, their advice is primarily committed to damage control, without taking the whole picture into account. Their recommendations are undermined by the political authorities. The competence in resolving crises of the latter seems to consist not only in consistently ignoring the economic dynamics behind the pandemic, but also in actively concealing them: while viruses, despite evidence to the contrary, whirled through the air in the park at night, they did not dare enter slaughterhouses, the politicians seemed to think. The curfew could thus be sold as the order of the day without affecting the production of surplus value. That is, after all, the main purpose of national politics, in which insights into more complicated circumstances only interfere, because they cannot be packaged in promotionally-effective slogans and scare away investors. After the fourth wave finally revealed that low vaccination rates threatened to cause a collapse of the battered healthcare infrastructure and to force the state to take measures that could impinge upon the profit-interests of individual capitals, the responsibility for the debacle was handed over entirely to atomised individuals: those who refuse to accept the effectiveness of vaccination have for the time being been all but exiled from social life, and even risk losing their jobs. In the spring of 2020, it was already apparent that the individualisation of responsibility was fuelling the general furore. Two years later, the willingness to vaccinate is drawn as a dividing line through society, along which the discontents of the pandemic can be collectively warded off. The clamour for compulsory vaccination is based on understandable fear and concern, but also on the attempt to conceal the serious consequences of state action. Coercion and the attribution of blame, however, will hardly be able to overcome the unwillingness of convinced opponents of vaccination.

The images of forest fires, droughts and floods that flicker across the screen in our living rooms have been announcing the uncontrollability of nature for some time now. The idea that the conditions for human existence are under threat and that the time for reaction is slipping away causes all kinds of anxiety : not only one’s own death, the death of the species is looming. Yet the gloomy outlook for the future of our time differs from the horrors of the past. Climate change is creeping in, its long-term effects on our own lives seem uncertain: record-breaking heat waves and extreme weather only vaguely hint at what is to come. Meanwhile, salvation from the calamity is sought in the processes of bourgeois democracy. And so for a long time not only did a Green Party chancellor in Germany seem possible, but other political protagonists who were previously known for lobbying for the coal and automobile industries unabashedly portrayed themselves as climate activists. But the hopes of an “awakening of climate politics” evaporated even before the new federal government had taken any official action. Fittingly, with a cheerful “make a wish”, the largest industrial nations dramatised their climate politics last autumn by collectively tossing coins into Rome’s Trevi Fountain, before making it clear at the UN Climate Change Conference in Glasgow that they were not prepared to take even remotely adequate measures.

Those elements of the destructive social relationship to nature which had been patched up in recent decades by environmental policy reforms are falling apart before our eyes. It has long been apparent where capital’s climate policy is heading: just a moment ago they were palavering about the lowest possible restrictions on emissions growth, now they can’t think of much more than passing on the costs of their ineffectual recipes downwards. The more radical parts of the climate movement have organised themselves against this. They have recognised that the climate question is posed in a class society. And it is dawning on them that a decent life under these conditions can only be achieved for the vast majority through universal emancipation. A left, though, that, like Andreas Malm, uses Bolshevik “war communism” as a middle-class bogey to push through left-social democratic policies, or that thinks it can instrumentalise the state for climate goals without any transformation at all, makes for a miserable coalition-partner.

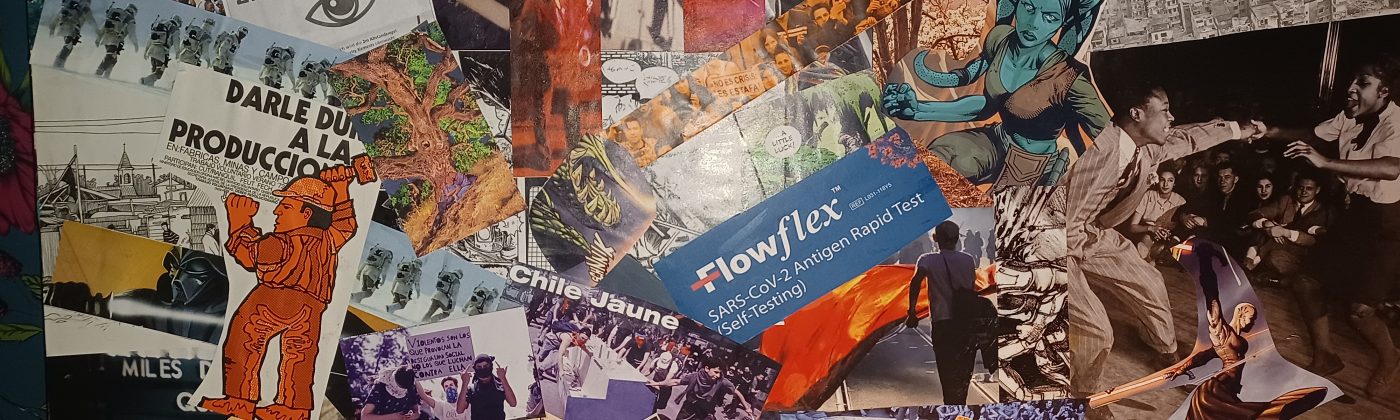

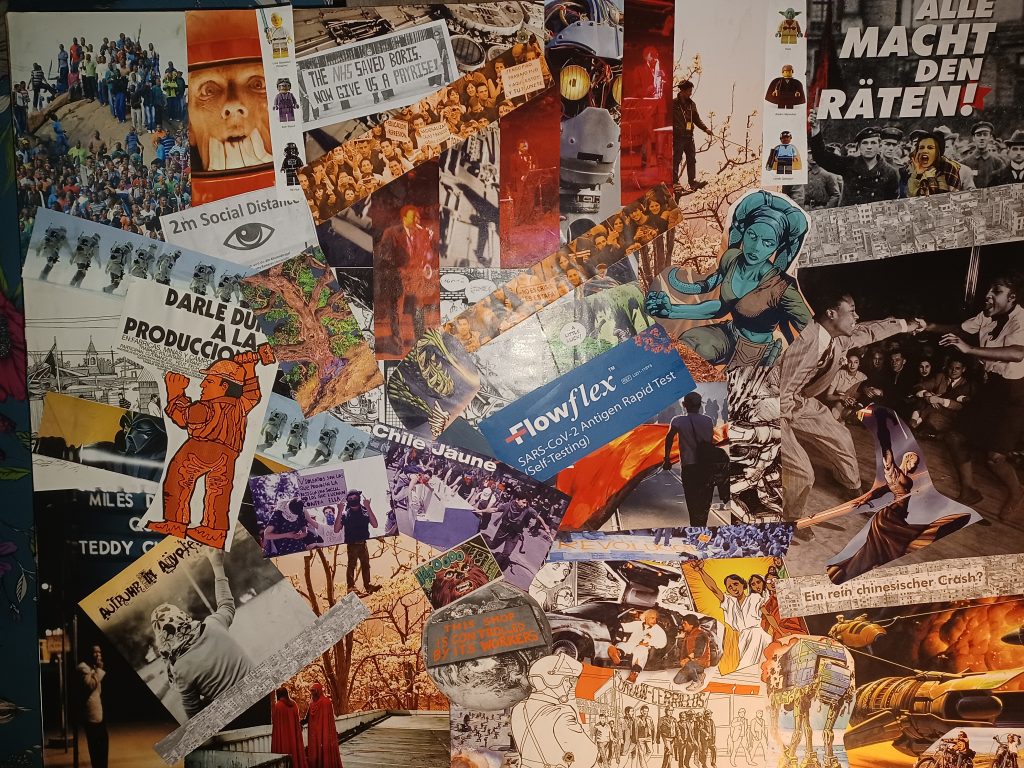

If there is anything to be hopeful about, it is the waves of social struggle that have been sweeping the earth for more than a decade: since the crisis hit in 2008, the vague idea of a free society has accompanied the mass mobilisations from Cairo to Minneapolis. It is still undefined, lacking theoretical contours and the first steps towards its realisation. The furious masses revolting against the imposition of a terrifying world are organised on a global scale less around the question of class than of political participation, gender identity, or dismay at racist and sexual violence. On the one hand, the mobilisations oscillate between the struggle for survival, anger over police violence, and defence against brutalised masculinity, but on the other hand, they also oscillate between authoritarian aggression, conspiracy delusions, and conformist rebellion. The social protests that swept the world before the pandemic may roll through again in the foreseeable, brutal clear-up of the ecological crisis. When the IMF recently warned of the loss of “social cohesion”, it may have had in mind not only the storming of the Capitol, but also the social revolts against the imposition of its world order.

But where hardship does not translate into viable mutual aid and hostility to the given conditions, it further brutalises individuals: inflamed by demagogues who merely deepen existing divisions but cannot offer a consistent programme, their cinematic palace-storms turn out to be a bizarre spectacle of enraged petit bourgeois, esotericists, and civil warriors with selfie sticks. If they were allowed to be even more unrestrained than they already are, they could unquestionably wreak even more havoc, but their unity is so fragile that a consolidation into power is unlikely for the time being. The “normal monsters” who wreak havoc as Querdenkers and Trumpists instead betray an uneasy truth about the objective disorder that is reflected in the subject.

The national incantations and expansive fiscal policy of the US government are intended to counteract the progressive loss of political legitimacy. After decades of domestic rearmament and the mobilisation of resentment, promises of a better life once again, for a brief time, seem to dominate political proclamations. In the EU, too, economic policy dogmas have been scuffed. Even in Berlin, word has apparently spread that the Eurozone and its advantages for exports cannot be had for free, and that there is now more at stake than the usual democratic power games. The suitability of the measures will have to be tested against the limits of economic possibilities.

Whether we are witnessing a historical turning point, as lamented by some and welcomed by others, will be determined by the course of accumulation. The frontlines of economic policy shift rapidly in such harsh collapses; it remains questionable how sustainable the short-term gains are in each case. What the two conflicting camps have in common is that the recurring crises remain a mystery to them. While the liberals believe in inflicting minor damage via flexibilisation, social cuts and wage reductions, the state leftists believe in social welfare to overcome the crisis. The market-believers are closer to reality with their idea of a cleansing crisis, they merely conceal the social devastation while they hurriedly diversify their portfolios and armour their mansions.

For the time being, the choice is between pestilence and cholera: long-lasting inhibitions on accumulation or a purge crash with brutal social consequences. The pragmatic state interventions to avert the latter cement overaccumulation by keeping zombie enterprises alive. Central banks continue to regularly pump tranquillisers into panic-stricken markets. In the end, the central bank paramedics and political figures, as busy as they are deciding on measure after measure, are at a loss.

In some places the powers-that-be are already struggling to patch up the national budget and at the same time keep the ever-flaring protests in check. Raising taxes on food, fuel, telephones, or higher public transport fares have failed again and again in recent years, from the Middle East to France to Colombia, due to massive unrest. In India, where almost half of all workers are employed in agriculture, Narendra Modi’s latest agricultural reforms, which would have triggered a comprehensive wave of privatisation and cost millions of farmers their livelihoods, failed in the face of months of mass protests. Now, in the face of political pressure from the country’s granaries, the economic pressure for agricultural industrialisation, and the full-blown health and hunger crisis, the Indian autocrat is increasingly running out of recipes for economic policy. Where misery can no longer be governed, blatant violence is resorted to; this does not however create “social cohesion”.

Hope also germinated in the protests against undisguised racist brutality. Initiated by black youth at the height of the first wave of infection, an uprising swept through almost all US cities under the ambiguous slogan “I can’t breathe”. The “George Floyd Rebellion” cannot be adequately explained by the chauvinism of the Trump era. Rather, it seemed to be a long-pent-up, diffuse rage unleashed after the glaring failure of government reached its sad climax in haggling over ventilators while bodies piled up in refrigerated trucks. The fact that there are a disproportionate number of non-white proletarianised people among the 800,000 or so who have now died and over 50 million who have been infected contributed to the extraordinary insurrectionary dynamic which immediately absorbed the lower-class segments and was radicalised through them. On the one hand, it is true that the recent protests have tended to be based on questions of state recognition – especially where the class is particularly frayed and the old centres of proletarian power have eroded. Identity is usually simply the first point of reference for disquiet in the classless class society. However, instead of joining the chorus of Sahra Wagenknecht and others and playing off a nationally-deformed concept of class against struggles for recognition, it would be better to analyse how specific oppressions and class interact – and how they could be eliminated in a common struggle.

The situation is chaotic and confusing; despite all the struggles, a world revolutionary movement is not visible. The fact that the struggles almost always fail and remain unconnected has for years given a certain impetus to traditional ideas of organisation: the party is supposed to fix it, it provides unity and continuity, offers a programme and leadership. Trust in pure spontaneity is far from us, and of course there is nothing to prevent social revolutionaries from joining forces to argue for their views; on the contrary. In the renaissance of party thought, however, as in the blessed days of the old workers’ movement, the organisation becomes the actual subject of the revolution; its growth is supposed to show how the class is doing. The class experiences an external, political condensation, which is built up as a mirror image of the existing state, which it is finally supposed to take on. This is far removed from the idea of the self-liberation of wage workers, who in the course of struggles, setbacks, and self-criticism educate themselves to become conscious social producers, starting from the given but harmful material connection between themselves. Hints of this could be seen in the pandemic, wherever workers independently launched strikes for factory closures or practised mutual aid. But such consciousness-raising by producers is also evident elsewhere. A recent study on the climate awareness of car workers shows that workers are not only concerned about their jobs, but also about the ecological failure of their industry. It has long since dawned on the producers that they are producing rubbish. What is decisive is not so much the degree of unionisation or a new mass organisation, but the extent to which there is such awareness of their own actions. This is also evident in the industrial action in Berlin’s hospitals in the face of the devastating health crisis. If the demonstrations were attended not only by nurses but also by all kinds of people who only know hospitals as patients, this is probably an expression of a consciousness of how important it would be to have this infrastructure in the hands of society. This underground fermentation, which also takes place where leftists would not suspect it, must be promoted.

Radicals should not distinguish themselves from reformist leftists by just constantly pointing to the limits that the current economic order places on daily struggles and rejecting concrete demands. Often, such demands are worthwhile, as long as one does not direct one’s forces solely towards them. In the pandemic, things like the abolition of private health insurance or the remunicipalisation of hospitals are urgent necessities; in view of the economic disaster in its wake, it will be necessary to push through financial support for the unemployed or the cancellation of rent debts. In contrast to the reformist left, radicals should nevertheless make it clear that such things come up against real, not merely pretended, limits of capital. Successful struggles by wage-dependents exacerbate the imbalance of the system, at least in the medium term – and do not bring it into balance by increasing purchasing power. In this respect, immanent demands are always fraught with contradiction: we weaken capital and the state while demanding something from them. This undermines the ability of the addressees to fulfil the demands.

This contradiction is not to be glossed over, but to be named. Transitional demands, the fulfilment of which is supposed to lead step by step out of capitalism, are illusory; at some point, the needs of workers expressed in the demands and the requirements of capital accumulation abruptly collide. Then one either buckles before the very real constraints of the capitalist mode of production or pursues its abolition. This would be the second difference to the reformist left: to put the prospect of a classless society on the agenda and to address proletarians consequently not as objects of state care but as potential subjects of social emancipation and self-organisation. However limited and short-lived the hints of this in the pandemic have been so far, revolutionary critique must make them recognisable as contours of the only conceivable way out of the whole mess. Only when the Commune becomes a conceivable option can one also fight for daily demands without worrying about the consequences for the reproduction of society.

The measures taken against the pandemic have brought class struggles to a standstill on such a broad front that intuitively one could almost agree with the left-wing dupes who think the whole thing is an evil hoax; by the early 2020s, from Iraq to Chile, from France to Sudan, there have been convulsions around the world as there have not been for a long time. As the viral scare subsides, such unrest is likely to return, and the existing order, meanwhile, has not become more stable. Working more, the French bourgeoisie has been telling its proletariat since the beginning of the pandemic, is the only conceivable answer to the excessive borrowing that has for the time being averted a severe economic crisis. If it is true that we will not see a permanent change of course with which a spendthrift social-democratic state celebrates its comeback, but that at some point the bill will have to be paid, then after the pandemic we could be in for some serious confrontations. This is no guarantee of anything, but the conditions for subversive activity could be worse.

Kosmoprolet, February 2022