A comrade from the US sent us the thoughts below in response to our text on revolutionary transition. The issue of transitional demands came up when raising the question of how the working class can accumulate forces for a collective take-over of the means of production:

Join the debate!

—————-

Notes on Transitional Demands

Put simply the transitional demand is a demand for the defense of the immediate interests of the workers emerging out of the concrete balance of forces which comes into contradiction with the stable reproduction of capital and its political superstructure. For the Second International the minimum program which asserted worker interests within the narrow limits set by the needs of stable capitalist reproduction was counterposed to an abstract maximum program.

The transitional or intermediate demand on the other hand is a demand for the defense of worker interests which is made with the awareness that its implementation will deepen the economic and political crisis. However, it does not explicitly call for the DOP, rather it serves to clarify to the broadest possible worker strata the ultimate need to impose the DOP as the only viable means of defending their interests.

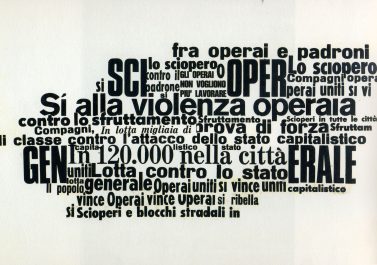

Taking a relatively recent example in the crisis of Italian capitalism in the Seventies the PCI as a good heir of the Second International explained to the workers that collaboration in the bosses program to restore national competitiveness was the only option. This was a faithful application of the logic of the minimum program as the law of value in fact “objectively” demanded an assault on the worker gains of the past decade. In this context asserting a defense of worker gains and blanket refusal of restructuring could only be understood as a system of transitional demands within a revolutionary trajectory. Such a defense was the most appropriate concrete form of a revolutionary line within the workers movement. Practically clarifying to the politically intermediate masses that reformism is structurally condemned to attack their day to day interests because of its investment in capitalist stability.

The refusal of the capitalist attack on labor market rigidity through restructuring and the purchasing power of the wage through inflation was the economic aspect of this system of transitional demands. The construction of organs of workers power to enforce these demands and the efforts to disarticulate the repressive apparatuses which impeded this construction was its political aspect.

It was the failure to make real inroads in the reformist majority which doomed autonomy to marginalization. Could this have been accomplished through a call for immediate offensive on the state to implement the DOP? Unlikely. On the contrary only the articulation of the concrete opposition between the reformist line of collaboration with restructuring and the revolutionary line of defending worker interests regardless of capitalist profitability had a chance.

As a 1979 article in the magazine Autonomia put it: “Alongside a program of organization, identification, exposure and appropriate militant response to the compromised revisionists, it is necessary to simultaneously develop as a priority, the practical and public political critique of their policy on the terrain of real class contradictions, on the real state of the balance of forces in this period between the proletariat and capitalism, in the factory, in the sectors of social production and in the territory [emphasis added].”

The Italian example is noteworthy because despite the lack of continuity between the political culture of the leaders of autonomy and the debates on the United Front in the KPD and Comintern which later formed a base for the Transitional Program the need to confront reformism practically on the terrain of the immediate struggles is the same. The question of transitional demands is the question of how to win a majority of the class to revolution not through abstract maximalism but through a “practical…political critique” of the incapacity of reformism to defend worker interests in the immediate struggle.

None of this to far off from the original application of the United Front policy (through no doubt Autonomy would have preferred a UF “from below”) in Germany. Where the KPD leadership called on leaders and militants of the reformist organizations to unite around a program of economic and armed defense of worker needs against the offensive of capital.

Trotsky’s Transitional Program forms another attempt to apply the same logic. In any case one should pose transitional demands not in order to hide your revolutionary politics but to clarify its concrete applicability within a specific balance of forces. And from a position within the struggles itself which allows the system of transitional demands to be synthesized on the basis of the requirements of the real movement.

All of this is quite far from sectarian and opportunist regurgitations of Trotsky’s specific formulas whose continued (non) relevance can only be determined on the basis of a systematic investigation. Regardless of the specific formulations the general principle remains valid.