English translation of the German article: http://www.heise.de/tp/artikel/48/48638/1.html

Ralf Ruckus and Jan Podróżny

(June 26, 2016)

PDF-File: RUCKUS_PODROZNY_2016_Amazon-Poland_2000-workers-want-strike

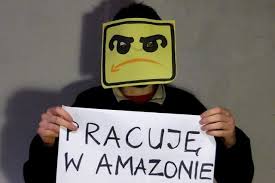

In Germany since 2013, workers organized in the Ver.di trade union at the online mail order business, Amazon, have frequently gone on strike for better working conditions and higher wages. [1] So far these have been the only official strike actions worldwide against the global company. But for over a year, workers at Amazon’s fulfillment centers in Poland, which mainly supply the German market, have been trying to open another strike front.

In a strike ballot in Amazon’s three Polish fulfillment centers near Poznań and Wrocław, which ran from late May to mid-June, about 2,000 workers voted for strike action. But no strike can be carried out under Polish labor law since less than fifty per cent of Amazon’s approximately 5,700 strong total Polish workforce participated in the vote.

The “Workers Initiative” grassroots union

The ballot was not organized by Solidarność (which like Ver.di belongs to the international UNI Global Union federation and which also has a presence at the Amazon centers in Wrocław) but by the grassroots union Inicjatywa Pracownicza (IP, Workers Initiative). IP has more than 350 members at Amazon – including more than 300 at the Poznań-Sady location and now a few dozen in the two Wrocław centers.

Dissatisfied Amazon employees in Poznań had started to build an IP group there in December 2014, three months after the center had opened. [2] They operate without paid union officials. Discussions and decisions take place solely through general assemblies and elected shop stewards who work on the shop floor like everyone else. [3]

Wildcat strike in June 2015

The ballot marks the highest point so far in a labor dispute that has been going on for a year. It began with a wildcat strike (not officially organized by the IP) in Amazon’s Poznań-Sady fulfillment center. On the night shift from June 24 to 25, 2015, dozens of warehouse workers protested against forced overtime.

Because of another strike at Amazon in Germany, management had moved work volume from Germany to Poznań at short notice and prolonged shifts there from ten to eleven hours. Workers in Poland were well aware that they were being lined up to act as scabs because for several days IP had been informing workers about the strike in Germany with leaflets and a banner on the access road to the fulfillment center. Therefore, the protest was also an explicit sign of solidarity with striking Amazon workers in Germany. [4]

During the wildcat strike in Poznań-Sady, “pickers” who collect order items from the shelves paralyzed the delivery process by making use of a bottleneck in the workflow. Usually they put about a dozen items in a plastic box and put it on a conveyor belt running into to the “pack” department. This time, they put only one item into each box, causing the belt to get clogged up with boxes in no time. Boxes started falling off the belt and the belt had to be stopped.

According to Amazon, productivity that night fell by 34 per cent. In answer to a fired warehouse worker’s claim against unfair dismissal because of his participation in the wildcat strike, Amazon describes – with remarkable candor – how to organize collective action in a warehouse:

“By putting only one item in a box […], the work process is consciously and deliberately slowed down, very much affecting steps further downstream in the process. Such an obstruction of the work process will lead to even greater potential losses and damages for the employer if a group of employees consciously and deliberately put single items into boxes. Such organized behavior will damage the overall ability of the logistics center to meet the needs of customers and lead to a significant loss of productivity, since it slows down not only the work of individual employees but also the work in the sorting and packing departments. It can also block the conveyor belt on which the boxes are standing, leading in turn to a standstill of the entire fulfillment process.” [5]

The direct reference to the labor dispute happening at the same time at the Amazon in Germany was possible because the IP members in Poznan-Sady had personally met Amazon employees from Germany at a series of self-organized cross-border meetings – a rare example of self-organized workers’ networking across borders. The shop floor activists from the German Amazon centers had informed their IP colleagues about the strike in advance.

Interrogations and redundancies

In the days and weeks immediately after the wildcat strike, Amazon took punitive action. While known IP activists were left alone, seemingly random workers who seemed less solid and well-connected were singled out, interrogated and then suspended, forced to sign termination agreements or fired. IP writes that during the interrogations workers were asked to sign statements about whether they had been involved and who had asked them to protest:

“Some left the interrogations with tears in their eyes, others signed declarations that they had deliberately worked slow and would do so again if the company would force them to work overtime again. We have advised colleagues not to sign any interrogation protocols or termination agreements. Several workers were suspended from work (with pay), others signed termination agreements and left voluntarily – most don’t want anything to do with Amazon anymore. In this way, Amazon ostentatiously punished a few randomly selected workers.” [6]

Almost a year after the wildcat strike, on May 31, 2016, proceedings began before the Labour Court in Poznań against unfair dismissal of one of the workers who had been fired. So far, no verdict has been reached and the next court date has been set for August – not uncommon in notoriously slow Polish labour courts. In a second case of another worker whose contract was not renewed after the wildcat strike, the first date took place on June 14 – also without a result. The next date has been set for October.

Wage increases in the aftermath of the strike

Immediately after the end of the wildcat strike in June 2015, IP officially started a labor dispute. Among other things, IP is demanding a raise of the basic hourly wage from 13 to 16 zlotys [about USD 3.20/4.00, GBP 2.40/3.00], longer breaks and annual work schedules instead of the current monthly work assignments. [7] Although IP has its main base in Poznań, the labor dispute involves all three centers in Poland because Amazon has bound them together into one legal entity.

In the negotiations with IP, Amazon made no concessions and, in December 2015, also broke off compulsory arbitration. However, already in August 2015, the company had increased the basic hourly wage both in Poznań-Sady and in Wrocław to 14 zlotys [about USD 3.50, GBP 2.60]. According to Amazon, there was no connection with the wildcat strike. IP shop stewards of the IP however are convinced that the wage raise is due solely to workers’ pressure.

In Germany, there had not been any wage increases either before the strikes started. Amazon has claimed it won’t sign a collective agreement with Ver.di, but since the strikes began they have granted several wages increases – although officially this has not been connected with the strike action.

The IP group continued to press their demands. After the breakdown of negotiations and arbitration they finally decided to ballot for strike action in mid-May 2016. [8] In order to combat Amazon’s typical division between permanent and temporary workers IP simultaneously held a strike ballot for Adecco, Manpower and Randstad workers, the agencies that supply Amazon Poland with temporary workers. This was possible because IP had also started labor disputes with the temp agencies in autumn 2015, which had also failed after negotiations and arbitration.

2,100 votes for strike – too little in Poland

The strike ballot was carried out jointly for all workers in the Polish Amazon centers – not only for about 5,700 permanent workers in Poznań and Wrocław combined, but also for about 4,000 temporary workers whose numbers vary greatly depending on the sales season.

Under Polish labor dispute law, unions may only call a strike if more than fifty per cent of the entire workforce participate in a strike ballot and if a majority votes in favor of strike action.

For that reason, the road to a legal strike in Poland is even more difficult than in Germany where a strike ballot is not legally prescribed. If a trade union decides to hold a strike ballot in accordance with its statutes the ballot is carried out exclusively among the union members in the company. 75 per cent of them must then vote in favor of strike in order to win the ballot.

According to figures published by IP on June 23 1,605 permanent workers and 496 temporary workers voted “Yes” in Poznań and Wrocław while 39 permanent workers and ten temporary workers voted “No”. [9] Not counting nine invalid votes, the proportion of “Yes” votes totaled 97.3 per cent. The number of “Yes” votes might have been enough for a strike even under Polish law if a majority of workers had participated in the strike ballot.

However, in the run-up to the ballot, Amazon management had held department meetings and warned workers in no uncertain terms not to participate in the strike ballot. Successfully it seems, as hardly thirty per cent of Amazon workers in Poznań and Wrocław ended up participating. Just for comparison: during the successful ballot at Amazon in Leipzig in March 2013 there were also 97 per cent “Yes” votes for strike. However, the ballot took place among only approximately 520 Ver.di members – not among the entire workforce of 1,900.

Solidarność abstains

Interestingly, Solidarność neither participated in the strike ballot, nor has it so far commented on it. Last year Solidarność publicly criticized IP several times for being too “confrontational” and “irresponsible”, portraying itself by contrast as a dialogue-oriented union cooperating with management for the benefit of the company. [10]

This is certainly in the interest of the right-wing PiS government, which is strongly supported by Solidarność. Most of all, Solidarność has no interest in a successful movement outside their organizational control. However, it is doubtful that in addition to that part of the workforce which has already been mobilized in favor of strike action by IP, Solidarność will find its own base among the workforce willing to stand up to Amazon.

Legal strikes or other industrial action?

So the way to a legal strike is blocked for the time being. However, the fact that nearly one-third of the permanent workforce and several hundred temporary workers voted for strike is a clear indication of the extent of dissatisfaction with the working conditions.

The IP union considers the high approval for strike action a good sign, but the low ballot turnout puts a question mark behind its current strategy. It is also unclear whether another, better-prepared ballot would bring a different result. Both the IP shop stewards and a majority of workers, however, expect a wage increase later this summer and the high approval for strike action might give Amazon the impetus to actually go through with it.

The question also remains how effective a strike within the framework of Polish laws would be at all. In Germany, Amazon has so far been able to dodge the strikes by shifting order volumes to other, non-striking centers – also the ones in Poland. To be effective, strikes would need to undermine this shift by paralyzing many centers simultaneously – also across the German-Polish border.

IP also promotes different forms of action. In its’ statement on the outcome of the strike ballot, it says:

“We already know the limits of a strike within the framework of Polish laws in our company. But strike action is not our goal as such. It is just one means for workers to exert pressure, but there are also other means: petitions, asking uncomfortable questions at stand-up meetings, not letting yourself be pushed around like cattle by managers, building contacts with Amazon workers in other countries, street protests – and many others.”

Footnotes:

[1]

»ver.di? Brauchen wir nicht…« Ein Gespräch mit Katharina Wesenick über Amazon

[2]

[3]

http://www.forum.ozzip.pl/wspieraj-ip/item/10-about-inicjatywa-pracownicza-workers-initiative

[4]

http://duepublico.uni-duisburg-essen.de/servlets/DerivateServlet/Derivate-41179/05_Ruckus_Amazon.pdf

[5]

http://www.labournet.de/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/amazon_pl13.pdf

[6]

http://www.labournet.de/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/amazon_pl13.pdf

[7]

http://www.heise.de/newsticker/meldung/Polnische-Gewerkschaft-fordert-hoehere-Loehne-fuer-Amazon-Mitarbeiter-2733314.html

[8]

http://www.labournet.de/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/amazon_pl12.pdf

[9]

http://ozzip.pl/teksty/informacje/ogolnopolskie/item/2134-wyniki-referendum-w-amazonie-ponad-2-tys-pracownikow-za-strajkiem

[10]

http://www.ozzip.pl/english-news/item/1955-das-wahre-gesicht-der-solidaritaet